Alex McAulay’s Don’t Tell a Soul defines “guilty pleasure.” I do not believe the grim, monochrome film was intended as such. I believe that McAulay aspired to make a somber piece about the dire sociopolitical state of this country, disguised as a tight little thriller. I believe that he wanted to portray the extremes impoverished folks resort to when push comes to shove. Most earnestly of all, I believe that the writer/ director sought to explore the intricacies of a brotherly bond, the sadistic power play involved, and how the aforementioned destitution may affect developing young minds. Then again, I may be wrong. Perhaps “guilty pleasure” is what the filmmaker was aiming for all along – in which case, McAulay pulls it off with aplomb.

He knows how to keep things tense. From the first minute, Don’t Tell a Soul grips you and doesn’t let go, even dragging you forcefully through its numerous rough patches. McAulay thrusts you into the life of Joey (Jack Dylan Grazer), an “almost 15-year-old” kid living in a dilapidated Everytown, USA. Joey’s father passed away from lung cancer; his diet-soda-addicted mother Carol (Mena Suvari) is currently dying of the same affliction. It’s up to Joey and his abusive older brother Matt (Fionn Whitehead) to take care of the frail woman.

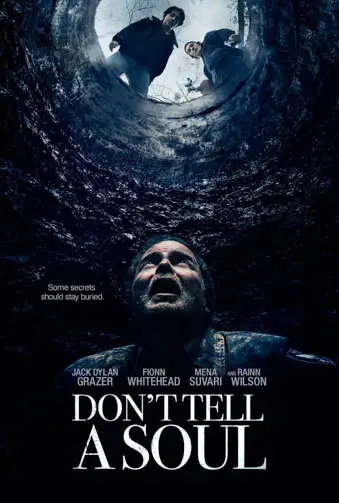

“…breathless chase through the forest ends with Hamby trapped in a deep, empty well, his ankle mangled…”

They’re neck-deep in debt. Matt comes up with a scheme to make some cash: there’s over ten grand stashed away in a recently vacated home that’s being fumigated for termites. Handing Joey a potentially useless gas mask he bought at the army surplus, Matt sends him in. It doesn’t take long for Joey to locate the money, but then the boys are busted by a security guard, Hamby (Rainn Wilson). A breathless chase through the forest ends with Hamby trapped in a deep well, his ankle mangled.

After some deliberation, the boys leave Hamby alone in the woods. Joey is ridden with guilt. Matt doesn’t care. “Say ‘F**k that man,’ on the count of three,” he forces his brother to repeat. Joey abides but goes back to the well the next day to strike an unusual conversation with Hamby. The increasingly empowered Matt (“Call me daddy,” he insists) joins Joey, but instead of helping Hamby, he urinates on him mercilessly, then does something even worse with a fumigation cylinder. A game of cat-and-mouse ensues, with twists both predictable and ludicrous. I’ll stop here before I start spoiling things for those of you who have never seen a movie before.

"…You’ve never seen Dwight Schrute get this crazy"