What we experience in childhood, to our person and to those around us, shape the very outlook we have on life. In turn, these experiences craft how we approach external pressures and determine the mental tools we utilize for internal crises. Andrew Rowe’s examination of the effects of childhood trauma between two estranged cousins sets the foundations for a fascinatingly brutal swirl of themes and genre tropes, ranging from typical crime drama plotting to arthouse introspection. While Crown and Anchor presents a unique, rather unflinching perspective on the fragile nature of the human psyche; it can easily be perceived as overlong and unnecessarily meandering.

“James and Danny’s shared scars split open as they are forced together, each weaponizing the past against the other…”

James Downey (Michael Rowe) is a teetotaling police officer with a considerable temper, resulting in multiple suspensions due to his handling of domestic abuse suspects; behavior endemic of his growing up with his heavy-drinking and physically abusive father Gus (Stephen McHattie). After he discovers his mother had passed away, James returns to his childhood hometown for the funeral. While sorting out his mom’s personal effects, James eventually gets after a local criminal outfit who are using his estranged cousin Danny (Matt Wells) to deal cocaine, all the while while Danny struggles to hide his mounting drug abuse from his wife Jessica (Natalie Brown) and their children (Sofia Wells and Alexander Wilson). James and Danny’s shared scars split open as they are forced together, each weaponizing the past against the other. However, they remain the only voices that can actually cut one another deep enough that their combined anger and guilt may avoid further tragedy for everyone else around them.

What is is absolutely front and center are the performances of the entire cast. Though there are scattershot awkward moments, they still manage to easily secure full immersion into a particularly dramatic scene, and then keep us there. While the blocking of the actors in some scenes is almost painfully obvious (as are scenes that mixed in improvisation with written dialogue), there are some truly amazing moments between Michael Rowe, Wells, and Brown. Though the real clincher exists in the chemistry between Rowe and McHattie during a brief but pivotal scene in the latter half of the film. That one seriously got me, and it was one of the most sinisterly subtle (and tragic) moments in movies this year.

“…a hard look on the how our childhoods turn us into the misfit adults…”

Adam Penney’s cinematography possesses multiple stylistic flourishes, with several scenes captured in highly involved singular takes snaking in and about the scene’s action. However, in many instances, their minimalist visual approach sucks dramatic tension from the scene, with several sequences failing visually due to poorly designed coverage. This unbalance is also directly reflective of Andrew Rowe’s screenplay and final cut. While there are many individual moments and sequences that are (almost unbelievably) gripping, taut and well-executed, others accentuate common storytelling pitfalls (such as succumbing to over-explanations when the established atmosphere is more than enough) and severely lacks a consistent rhythm. There is an abundance of elements to enjoy, respect, and ponder over, but the movie is also overburdened with roughly 20 minutes of excess fat.

Even with its nagging, lumbering elements, Crown and Anchor succeeds in taking a hard look on the how our childhoods turn us into the misfit adults we are, and not to find answers, but to simply (and starkly) observe the effects.

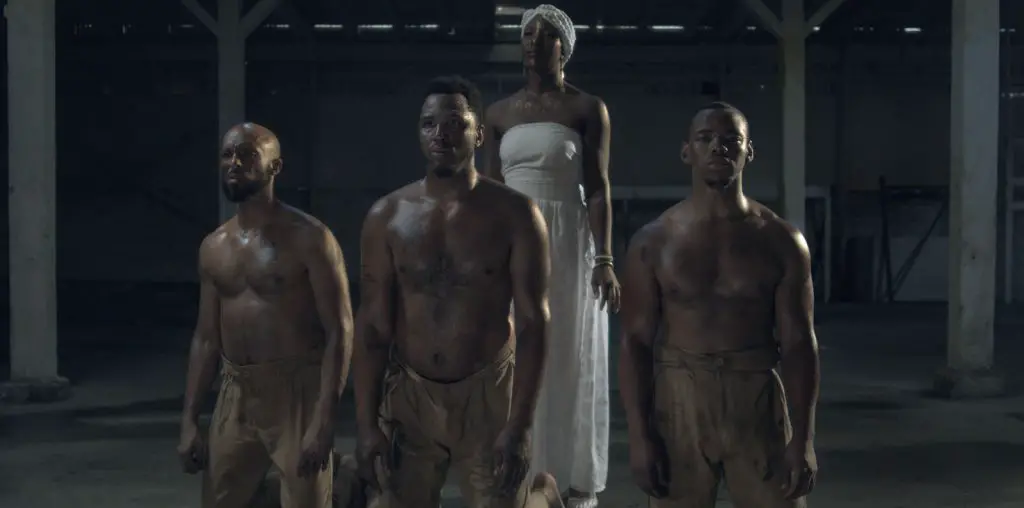

Crown and Anchor (2018) Directed by Andrew Rowe. Written by Andrew Rowe. Starring Michael Rowe, Matt Wells, Natalie Brown, Stephen McHattie.

6 out of 10

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ryUCcSU6-Q0