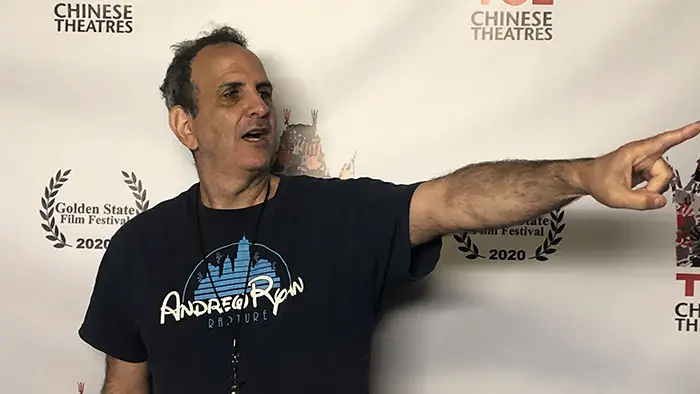

You can say one thing for writer/director Richard Halpern – the man has vision. As any independent filmmaker, or any filmmaker for that matter, will tell you, it all begins with an idea. Mr. Halpern takes an idea and, faster than you can say “first-look deal at Paramount,” he is off to hit the celluloid.

His new film, for which Halpern is presently enduring the make-or-break process of marketing and distribution, is the smart, contemporary, and haunting Suburban Nightmare. The thriller concerns a family of four as a psychotic houseguest terrorizes them in a terrifying riff on the contemporary house-sharing phenomenon. Halpern conceived of Suburban Nightmare while he was in a temporary boarding situation in a strange family’s home. Halpern states, “I thought to myself, is it worth risking the lives of your children by having a stranger inside your house? For 80 bucks a night? I immediately began to write Suburban Nightmare.”

“The independence of not having a studio to answer to and the freedom to tell the story that he wanted to tell.”

Embracing the independence of not having a studio to answer to and the freedom to tell the story that he wanted to tell, Halpern chose not to work with a traditional script. Instead, Suburban Nightmare was filmed as an improv-style exercise with only an outline and story beats for the actors to hit, a la the Ryan Gosling-Michelle Williams drama Blue Valentine and the HBO show Curb Your Enthusiasm. Star Malcolm Mills, who menacingly inhabits the psycho-boarder who drives the titular nightmare, recalls, “It was great fun to have freedom within the guided improv, adding extra layers of unpredictability and realism.”

The freedom of playing with a story as it is concurrently put to film is made somewhat more viable in an independent film. It is rare not to experience interference from a production company or studio backing a project when a filmmaker is spearheading a major Hollywood movie. On those sorts of productions, there are several people whose input the filmmaker must take into consideration: studio heads, heads of production, actors agents, talent, etc. While a nice healthy budget might make for a great looking film and afford big stars for that all-important opening weekend, it also has the potential to restrict the type of breathing room enjoyed by frank collaboration amongst a ragtag group of artists unconcerned with anybody’s input but their own.

Such is the spirit in which Suburban Nightmare was brought to life. Most of the financing was secured primarily from Halpern’s brother, Philip, and past professional relationships were reignited (Director of Photography Henry Less, a colleague of Halpern’s, provided the cameras and drones for the shoot solely for backend points and credit). In true independent spirit, the cast was the crew (star Mills scored the film), and the crew was the cast (the home that served as the movie’s principal location was provided by co-star Sandra Rossi). Everyone was involved in every aspect of the production in one way or another, whether contributing money, resources, or individual talent. Paradoxically, the making of Suburban Nightmare resulted in quite a familial production for a story about a familial nightmare.