“‘Make it according to the formulas that we like. We like movies to be normal but well-done,'” Francis Ford Coppola said, summarizing what he considers the sternly unadventurous view of many film critics. “The Guardians of Film are very tough about, you know, it can’t be pretentious, it can’t be self… what’s the word they use a lot? – There’s another word like ‘pretentious’ which means you tried too much… self-indulgent.”

Well, guess what? Coppola, the director of the “Godfather” trilogy, “Apocalypse Now,” and “The Conversation,” isn’t working for the studio these days, and he certainly isn’t working for film critics. He’s got enough money to finance films out of his own pocket, and he’ll indulge himself just as much as he likes, thank you.

“If you’re a young writer, just steal from who you like.”

I met Coppola on a rainy morning in a suite at New York’s Beekman Tower Hotel to discuss his newest film, “Tetro.” Seated at a table with me and two other journalists, the legendary New Hollywood auteur was bearded and jovial, frequently rocking back in his chair and splaying his arms wide to illustrate particularly expansive points (“Probably ninety-five percent of greatest movies ever made were in black and white!”) or hacking the air with his hand to emphasize heartfelt advice (“If you’re a young writer, just steal from who you like. If you want to write a John Steinbeck book, try to: You can’t! And you’ll find out that although that’s like a beacon to inspire you, what you can write will come out as your own, and that’s how you begin to have your own voice”).

The director, who turned 70 this year, seemed happy, with the confidence and occasional exuberance of an artist decades younger. “Tetro” is, after all, the second film of his “new career,” one in which all final creative decisions rest with him and he is free to pursue only the subjects which truly interest him. “The rules of the career are different,” he said. “I only want to write the screenplays. I don’t want to ever direct something that’s been given to me, as I did especially during that period when I was in my forties.” He was presumably referring to the period in the 1980s when he made films like “The Outsiders,” “Peggy Sue Got Married,” and “Tucker: A Man and His Dream.”

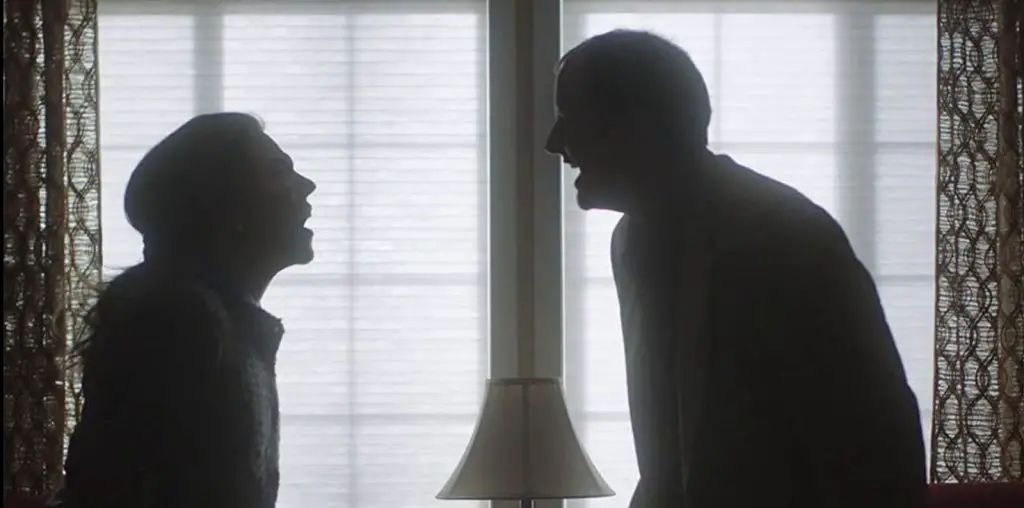

“Tetro,” in this writer’s opinion, is a better and more interesting movie than any of those. Shot in lush, silvery black and white, the film follows 17-year-old Bennie Tetrocini (Alden Ehrenreich), a military school runaway and cruise ship waiter who travels to Argentina to find his half-brother Angelo (Vincent Gallo). Angelo, now known only as Tetro, is a surly, selfish, temperamental writer who has rejected the family. Their father, Carlo (Klaus Maria Brandauer), was an egomaniacal bastard who tore the Tetrocini clan to bits, as we slowly learn by way of flashbacks in which gorgeous color and elegant hand-held cinematography contrast with emotional violence.

According to both Coppola and Ehrenreich, large chunks of the film were improvised (and the plot changed as a result). You can feel it. Minor inconsistencies and implausible zigzags bedevil the plot, but the performances come across vividly and Coppola’s personality as a director is strong, which is to say that “Tetro” is frequently delightful and always engaging, even when it’s also preposterous.

Coppola drew an emphatic contrast between “Tetro” and his last film, “Youth Without Youth,” which he seemed to regard as more abstractly philosophical. “‘Youth Without Youth’ is a good example of a movie that didn’t follow the rules,” he said, referring back to the supposed edicts of the Guardians of Film. “And as a result, you know, no one went to see it. So I felt, gee, you know, people really don’t want to see films that deal with philosophical ideas, people want emotion. So what could I write that would have emotion in it? And I said, well, my family makes me emotional… so I tried to write something that I felt emotional about, so that it would be heartfelt. And I learned a lot about myself, that I didn’t know why I was sensitive about certain things. When you write a script, it’s like asking a question. And when you finish the film, you get some of the answers.”

“When you write a script, it’s like asking a question. And when you finish the film, you get some of the answers”

The Coppola alter ego in “Tetro” is Bennie, the military school runaway (the director says he ran away from military school, too) who’s desperate for the love of his absent older brother. When casting for the part, Coppola had a very clear idea of what he didn’t want. “James Dean was a high school student in ‘Rebel Without A Cause,’ but I never thought he looked like a high school student,” Coppola said. “So I wanted to look at really young people… we looked at high schools and high school drama programs.” And that was how he found Alden Ehrenreich, who Coppola describes as “a much handsomer version of me.” After asking the young actor to audition by reading from Catcher in the Rye, Coppola decided he’d found his Bennie Tetrocini.

Ehrenreich, now a 19-year-old NYU student, was also at the Beekman suite doing press for “Tetro” and looking rakishly exhausted. A slight young man with florid eyebrows and an affable, expressive demeanor – as well as a strong facial resemblance to both Montgomery Clift and Leonardo DiCaprio – he seemed to have staggered in on fumes. Like his character in the film, Ehrenreich is an aspiring writer (he’s working on a play inspired by a group of homeless youths who lived a block from his East Village dorm), quite articulate, and it was easy to see why Coppola considered him a good fit for the role.

The two of them, more than fifty years apart in age, had a well-worn rapport. During Coppola’s interview, we heard loud, jaunty whistling from the hallway. “SHUT UP, ALDEN!” Coppola yelled, feigning gruffness, “I got my radio mic on.” The whistling stopped. Coppola shook his head. “He always whistles.” Then the whistling started again – further down the hall.

At this stage in his career (or, as he prefers, careers), Coppola doesn’t need to make films that are profitable or compatible with pop culture. He obviously wants intelligent filmgoers to see and enjoy his work, and he spends time actively thinking about how to engage them – but even that doesn’t seem like his driving impulse these days. After listening to him speak for a little while, it becomes very clear that his primary motivation in his “second career” is self-exploration. He does all his location-scouting alone, immersing himself in the culture where the film will take place (Romania for “Youth Without Youth”; Argentina for “Tetro”), and he writes the scripts and conducts the improvisatory rehearsals with personal questions in mind: What does it mean to get old? What is my obligation to my family? What are their obligations to me?

“When you get old,” he said, “you realize that of the pleasures of life, all the things, you know, ‘Oh, I’m gonna have my own jet plane, I’m gonna have thousands of girlfriends, I’m gonna have a big mansion’ – you realize that’s not so much pleasure. Real pleasure is to learn something. And that’s what I do.”

Nice work if you can get it.

Originally posted on June 11, 2009.