Get Real (1998), directed by Simon Shore, is a British film that, in a painfully realistic way, portrays the day-to-day experiences of a whole generation of LGBT youth. Rather than a sanitised, “feel-good” take on same-sex relationships, it follows two boys—Steven Carter (Ben Silverstone) and John Dixon (Brad Gorton)—whose rollercoaster romance forces each to question themselves deeply and collide with family and society. The rest of the cast (Linda, the best friend, Steven’s strict dad, and a well-meaning mum) remain mostly caricatures, framing Steven and John’s inner journeys rather than driving them.

Get Real came out in a decade when homosexuality was still far from accepted. Section 28, introduced by the Thatcher government, banned local authorities in the UK from “promoting” homosexuality and effectively erased queer lives from public institutions. And yet—perhaps even in defiance of that repression—this small, independent production burst onto the scene with irreverence. Unlike Maurice (1987), which strategically set its story in the Edwardian past to ensure a safe historical distance, Get Real lands firmly in the contemporary moment. It dares to follow a gay teenager precisely where Section 28 insisted he shouldn’t exist: in school. There are countless anecdotes online about closeted teens sneaking away to rent the VHS of Get Real, just to see a hidden part of themselves on screen, finally.

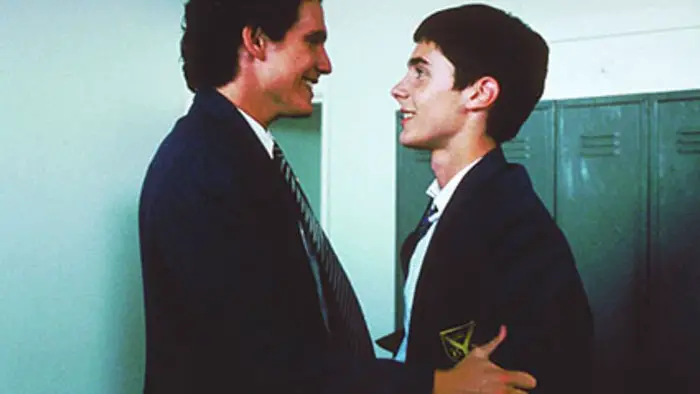

Brad Gorton and Ben Silverstone as John Dixon and Steven Carter in Get Real (1998), caught in a fleeting moment of connection amidst the tension of closeted teenage life.

“Get Real lands firmly in the contemporary moment. It dares to follow a gay teenager precisely where Section 28 insisted he shouldn’t exist: in school.”

Steven has long known he’s gay but has remained closeted—except to his best friend Linda, with whom he shares stories of his sneaky sexual encounters. That’s the constraint of a homophobic society: love becomes impossible, and sex gets pushed into the margins, both literally and figuratively. The other main character, John Dixon, is even more deeply fragmented. He hasn’t yet accepted his sexuality and goes cruising in public toilets, all while having a girlfriend. For both, the closet serves as a shield from society. Steven is severely bullied and wonders what they’d do if they actually knew he was gay. John, coming from an affluent family and destined for Oxford, also happens to be the school’s star athlete, and he has to keep up appearances to protect his reputation. The film doesn’t offer a clean, uplifting narrative where coming out equals liberation. Instead, it explores how devastating the internal conflict can be when the desire to love someone clashes with society’s expectations.

These conflicts—between desire and love on one side, and repression and shame on the other—play out vividly in the film’s key moments. An early pivot occurs in a public toilet, when Steven unexpectedly discovers John is also gay. Ironically, the pop song “Love Is All Around” plays softly during their anonymous, coded encounter. Afterwards, John completely denies what happened, even feigning shock when Steven calmly admits to being “dodgy.” This denial, especially since John initiated the encounter, sets the tone for their emotionally charged, contradictory relationship.

Great article, but the film is available on Amazon Prime and on YouTube.