Haunted Homes examines not only the growth of the suburban neighborhood but also its long-term impact on American identity and the American family as depicted in US film and television. Suburbia is not just an architectural choice or geographic preference. Suburbia establishes and reinforces specific modes of behavior, not all of which come with messages of opportunity and hope. It shifts focus to the family while, at the same time, isolating the family—from other people and the individual members from each other. It is a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between city and home, between husband and wife, between job and family, between private and public space.

In the decade that followed the collapse of the housing market in 2008, as owning a home became more difficult for thousands of Americans, it also became more difficult on-screen. Haunted home narratives began growing in popularity. Whereas Hollywood only produced eight haunted home films between 1980 and 1987, it produced thirty-two films that included haunted homes between 2008 and 2016. It was not just that people realized homeownership was less accessible than they had been led to believe. It was that homeownership became a literal nightmare, and Hollywood, as it often does, tapped into the zeitgeist.

Financial duress is a frequent plot point in many haunted home narratives. After all, if your house is haunted, the logical response would be to leave. However, something prevents these homeowners from leaving, and in the vast majority of cases, that reason is financial. People stay in bad housing situations because they cannot afford to leave. People stay because all their money has been invested in the aforementioned house, often purchased at a steal for reasons that soon become obvious, and so they cannot move. Haunted home narratives frequently beg the question: What is more terrifying, the supernatural or bankruptcy?

In an exchange from Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (Troy Nixey, 2010), that could just as easily be from any number of haunted home movies, Kim (Katie Holmes) tells her boyfriend, Alex (Guy Pearce), that they must leave the house. Alex does not take Kim seriously, protesting that every cent he has “is in that house,” and Kim ends up dying as a result. In the episode “Murder House” of the television series American Horror Story: Murder House (FX, October 19, 2011), the first season of the horror anthology created by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk, Vivien Harmon (Connie Britton) begs her husband, Ben Harmon (Dylan McDermott), to let them move. She knows the house they just bought is evil and will destroy them. He tells her that they cannot move because they cannot afford it. When she asks if they are broke, he says no, they have money, but it is “just tied up in this house,” and they cannot get it back until they sell the house. In other words, the house owns them. In the episode “Halloween: Part 1” (FX, October 26, 2011), former residents of the house are shown via flashback also wanting to leave. However, Chad (Zachary Quinto) similarly tells his partner, Patrick (Teddy Sears), that they cannot leave because all their money “is in this house.” They had planned to flip the house and “make a mint on it,” but now they cannot “because the economy is in the shitter,” as Chad explains. Like the Harmons, they are stuck.

The idea of profiting off a home purchase that then becomes a disaster is a central tenet in the Netflix television series The Haunting of Hill House (Mike Flanagan, 2018), in which the Crains buy an old home with plans to renovate and then resell it, just like Chad and Patrick. Initially, they are preoccupied by the money they will make by flipping, while the children are excited about the sheer size of the house. In the episode “Screaming Meemies,” when the Crain family first arrives at Hill House, the children react with awe, describing the house as “insane,” “a castle,” and “bigger than anything” they have seen. The mother, Olivia (Carla Gugino), cautions her children that there is a lot of work to be done on the house but that once they are finished—and here Hugh (Henry Thomas) interrupts his wife to declare, “We’re gonna be rich!” Olivia cautions her husband not to speak like that in front of the children, but Hugh’s exuberance is unrelenting: “We’re gonna be swimming in it!” he declares. By “it,” of course, he means money. They forgot to take into account the supernatural.

Homeownership also promises fresh starts. In a flashback within the American Horror Story: Murder House episode “Afterbirth” (FX, December 21, 2011), Vivien tells her husband, Ben, that she is going to leave him and move to Florida after finding out about his recent affair with one of his students. He pleads with her to reconsider, to let the family have a “fresh start” in Los Angeles. When she refuses, saying that she cannot get past the affair, he shows her a photo of a house he wants to buy in Los Angeles. “It’s right near Hancock Park, where all those big mansions from the ’20s are. You always talked about how much you wanted a house like this,” he says. He even jokes that maybe the house is haunted because the price is such a steal, but that seems a small price to pay (literally) for such a bargain. This house, he swears, will make their family whole again. “When I look at this place, for the first time I feel like there’s hope,” he says. It is clear that Ben sees homeownership as a magical salve that will heal all their wounds.

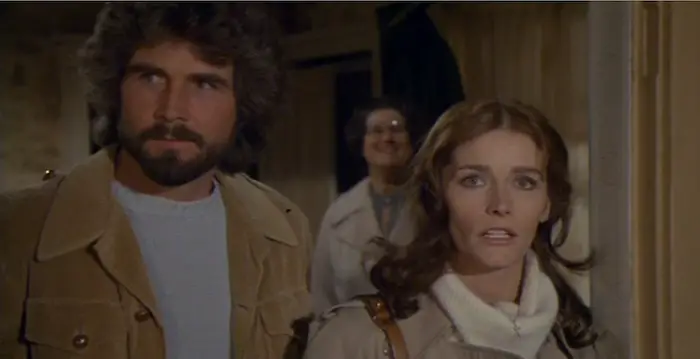

The ideal of homeownership at a bargain is also an incentive in the first film of the Amityville franchise, The Amityville Horror (Stuart Rosenberg, 1979). A few minutes into the film, a real estate agent shows the Amityville house to George (James Brolin) and Kathy (Margot Kidder) Lutz. After the couple find out about the house’s past—in which the Montelli family was murdered—they withdraw to the attic to discuss the situation. Kathy tells her husband that she loves the house but that she is disturbed by the house’s past. However, her husband, who insists that “houses don’t have memories,” and therefore that the murders are not an issue. He also points out that if the murders had not happened, there would be no way they could afford the house, which is all the encouragement Kathy needs. When the Lutz family moves in, we find out why buying the house had felt so unattainable for Kathy. “This is a big event in my family,” she tells George. “We’ve always been a bunch of renters. It’s the first time anyone has bought a house.” It is almost understandable that an accomplishment like that would make one overlook a murder or two.

Whether consciously or not, Hollywood has continued to promote the image of suburbia with its uniform houses and uniform heteronormative families. Hollywood has also continued to reflect the glory of homeownership, the way that owning a house seems to fill so many of the requirements of successful adulthood, whatever the price.

“Anyone who has ever owned a home knows the terrors of getting a mortgage and closing. So it should surprise no one that the source of pure evil turns out to be… home ownership. Dahlia Schweitzer’s brilliantly-crafted collection of insightful essays provide a perfect autopsy of the haunted house genre. Haunted Homes is not just a useful dissection of a popular subgenre of horror, it provides the perfect re-watch list for fans seeking to go layers deeper to confront their inner fears.”

– Chris Gore, FILM THREAT

About the Author

Dahlia Schweitzer is an Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. Previous books include L.A. Private Eyes, Going Viral: Zombies, Viruses, and the End of the World, and Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer: Another Kind of Monster. Dahlia Schweitzer’s Haunted Homes book can be ordered here and you can get more info at thisisdahlia.com

[…] Exclusive Excerpt from Dahlia Schweitzer’s Haunted Homes Film Threat Article Source […]