“Deprivation” is a new-classic example of how to take a great idea and spin it into a not-great movie. You know a film has problems when the 78 minute running time was cut down from 150 hours of footage–and of the 78 minutes that remained, more than half is barely functional.

The film takes place in a pre-9/11 New York (the World Trade Center is seen in the opening montage) and focuses on Steven, a somewhat creepy loner with a boring job (he literally falls asleep at his work cubicle) and a pathetic approach to love (he stalks a Hasidic Jewish woman in his Brooklyn neighborhood and chats up girls from scuzzy escort service advertisements). Steven’s life is abruptly shaken when his high school friend Thomas comes crashing into town. Thomas is everything Steven is not–gregarious, impulsive, risk-taking–and some things he should not be–obnoxious, immature and prone to evasions and lies. But the reunion is ill-matched and problematic, as the activities the men share (whether it involves a basketball match or a hook-up with a high school pal) inevitably end with deep problems. During Thomas’ crash in Stephen’s tiny apartment and tiny life, there is an avalanche of talk and in time buried truths about both men come out. For Steven, it is the roots of his inability to secure a happy and healthy relationship with women. For Thomas, darker corners of his life and personality are exposed with disconcerting results.

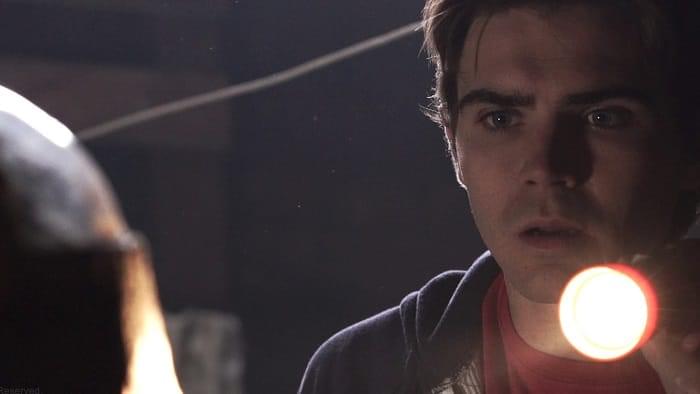

The basic set-up of “Deprivation” is more than adequate for a memorable film to be built up, and the rapport between the actors Neil Driscoll Jr. as Steven and Jeremy Davidson as Thomas is uncommonly strong in pushing the film to that goal. The actors improvised much of their dialogue along the screenplay’s arc and they respond to the depth of their roles beautifully. Davidson has a striking and kinetic screen presence that gives him bad-boy appeal even when his character dips into boorish behavior, while Driscoll infuses the less-flashy role with a subtle sense of inner torment trying to break through a crumbling outer protective shell of studied indifference.

But where “Deprivation” fumbles is the manner in which it is presented. Director Jesse Scolaro inexplicably decided to give the film a nausea-inducing visual style complete with annoying handheld cinematography and hiccuping editing. So much of “Deprivation” is nearly unwatchable because the camera cannot hold still while the editing chops and slices the scenes without any degree of rhythm or purpose. The actors’ work in creating such unusual characters is undermined by a technical approach which turns the performances into character assassination. It becomes difficult to focus on what is happening in the story when the camera itself can’t keep its focus (literally and figuratively).

“Deprivation” also takes a very dark and strange final act turn which seems to come out of nowhere and leaves the film with a sour and miserable coating. Without spoiling the ending (which would be redundant, since it is rather spoiled already), “Deprivation” goes into dark psychological and physically violent territory where it does not belong and should not have tiptoed in the first place. Instead of giving the film a gritty wind-up, it instead lobs a grimy cop-out which cheapens all that came before it. And even the intense acting of the film’s stars cannot make sense of the very wrong final note they are forced to play.