NOW ON MUBI! Athina Rachel Tsangari’s surreal allegory, Harvest, is the perfect example of “hard to love, easy to admire.” It’s an art piece with lofty ambitions, and the running time to match them. Not much happens during the 133-minute visually splendid study of a village and its inhabitants over a week’s period, yet surely Tsangari would argue that a tremendous deal occurs, a bottomless well of wisdom and insight is revealed, each wisp of the wind through the cornfields a symbol of encroaching change. Fine, but the non-narrative holds one at arm’s length, or perhaps even two, rendering the proceedings oddly flat despite the clear and at times impressive shrewdness.

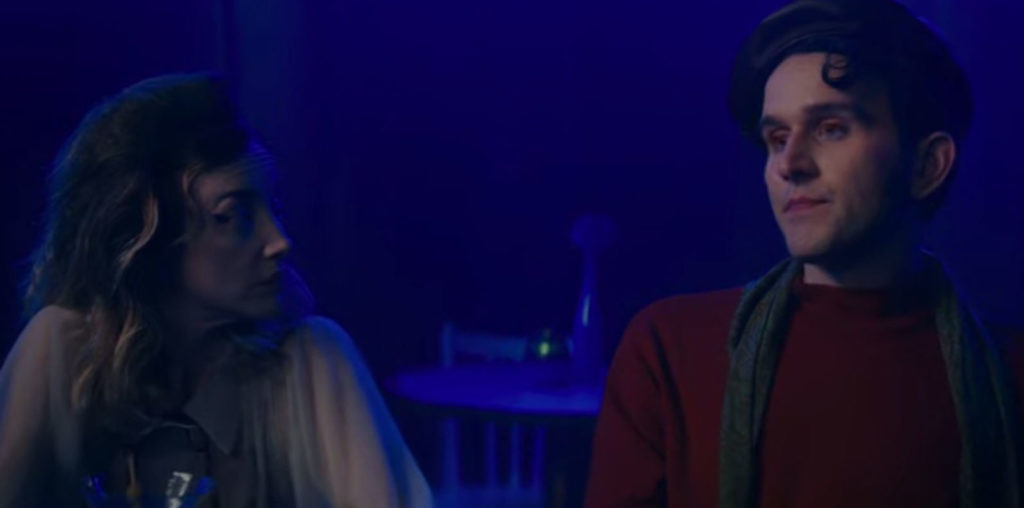

Widower Walter (Caleb Landry Jones) swims through a field of hay, eats branches, studies bugs, and sticks his tongue into trees. He’s part of the Amish-like village in an undisclosed location, out of place, out of time. Folks don self-made garb, speak in an eccentric dialect (“We have become like animals… goat drunk and lecherous. Dog drunk and barking mad,” Walter states), and live off the land, yet there are also traces of modernity. Presiding over the village is Walter’s friend, the well-meaning but misguided Master Kent (Harry Melling).

These people know their plants, what’s edible/medicinal (“everything here will either give you the s**ts or keep you from getting them…”). They also “bump their children’s heads against the boundary stone so they know where they belong.” Since it’s harvest time, they dine, dance, and chant together by the fire to medieval tunes. “We are sitting warm at home, weaving fortune for ourselves from yarn,” a proud Master Kent proclaims.

Villagers assemble in traditional attire during harvest rituals in Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Harvest

“…outside world begins to seep in, horses get murdered…”

But then things unravel. Unwelcome visitors get punished for burning a farmhouse and “dining out on fowl that don’t belong to [them]”; they are forced to stand in pillories for a week. Walter seems to be the only one attempting to help the bitter men. Particularly notable is that the village folks are all white, responding with great suspicion to two Black newcomers, especially the woman, cutting off her hair and shunning her. The outside world begins to seep in, horses get murdered, seeds of capitalism, industry, greed, and corruption are planted, and, as their land gets mapped, the inhabitants get “drawn out of existence”.

A series of bird’s-eye view shots reveals the residents as ants, scurrying about their duties. This is how Tsangari regards humanity and its eventual demise. The filmmaker coolly observes the inevitable through Caleb’s sorrowful, empathetic eyes (the always excellent Jones, restrained here). Humanity is doomed, but nature is ethereal, lovely, captured in glorious sepia tones. This is pure cinematic meditation, requiring a surrender to its languid tempo and hallucinatory vibes. For a fable about humanity, there’s surprisingly little warmth here, next to nothing resembling a real, relatable connection. There’s only so long one can admire the imagery and costumes before yearning for something more, a little zing in the proceedings.

Think The Wicker Man or Midsommar without the encroaching horror, or a stretched-out The Village sans the shocks or twist ending, or even a less artsy, but also significantly less powerful, Dogville. Harvest seems to draw inspiration from these studies of cults, but also dials things down and stretches them out, all in the mood, atmosphere, and style. The pitch never rises, which is bound to test one’s patience, despite the occasional recognition of true ingenuity.

"…pitch never rises, which is bound to test one's patience"