Dominik Graf’s Fabian: Going to the Dogs isn’t your typical historical romance. The seasoned German filmmaker expands Erich Kästner’s 1931 slim novel Fabian: The Story of a Moralist into a three-hour, experimental epic, continuously subverting expectations and resolutely avoiding predictability. A glossy Hollywood throwback it’s not, but those attuned to its wavelength are bound to find themselves mesmerized.

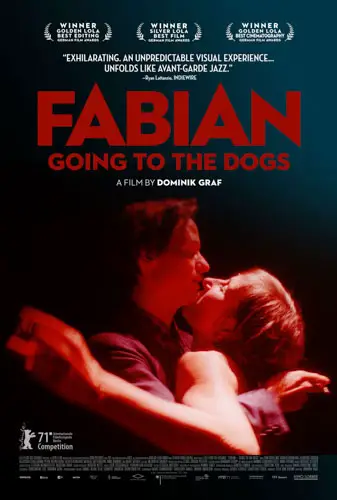

The opening tracking shot glides through a modern-day subway station in Berlin before transporting the viewer to the 1930s upon emerging into daylight. Jakob Fabian (Tom Schilling) is an ad associate/aspiring writer by day, debauched street wanderer by night. After nights of inconsequential sexual shenanigans, he falls for Cornelia (Saskia Rosendahl), a film-lawyer-in-training who dreams of becoming a star.

At first, the couple is passionately in love. As things look up for Cornelia, however, Jakob’s life falls apart: he gets fired, the lack of income begins to have its toll, and then there’s his rich, handsome, politically-involved friend Stephan (Albrecht Schuch) – an ambiguous presence, both a friend and a threat. Jakob gradually distances himself from his true love, reexamines his own vanity, and deals with a tragedy.

Graf’s film consists of disparate elements that shouldn’t cohere but somehow do. A wonderfully disorienting opening choral soundtrack jarringly morphs into punk rock; before one realizes it, classical orchestral motifs are driving the narrative. At first, the rapid-fire editing and imagery have an abrasive effect, but Graf expertly assembles these elements into a fluid, rather sophisticated narrative. Lo-fi footage goes hand-in-hand with archival shots, POV shots, split-screen, and fast motion. Further complimented by somber narration, it all feels both anachronistic and oddly fitting.

“…an ad associate/aspiring writer by day, debauched street wanderer by night…”

Fabian: Going to the Dogs is poetic, ugly, romantic, tragic, and side-splitting. Some sequences approach the edge of sanity, take a glimpse into the abyss, then the plot reassembles itself – but the threat of derailing remains, and it’s quite exhilarating. Early on, Jakob gets entangled in an off-kilter (to put it mildly) contractual obligation with a doctor and his sexually-demanding wife. A brief flash-forward gives the viewer a taste of Jakob and Cornelia’s tragic romance. Cornelia folk dances in the nude. Jakob applies soothing cream to a nasty wound on a large man’s sagging stomach. The final scene is absolutely gut-wrenching in its nonchalance.

Graf, who co-wrote the film with Constantin Lieb, has a great ear for dialogue that resonates without sounding forced. “The only thing I’ve not experienced is suicide,” a character says, “but there’s still time.” Another character proclaims: “Starving is a matter of taste.” My favorite line may belong to a philosophizing Fabian: “You can always find a man who’ll block a woman’s path.”

The central trio is spectacular. Schilling – who unnervingly resembles James McAvoy – maintains a fine balancing act of cynicism and earnestness. “At night I dream I’ll lose her,” he laments. “I’m ashamed of it.” It’s a carefully calculated, introverted performance that holds one rapt. Rosendahl keeps up, her Cornelia tender and determined, unwilling to let the oppressive regime, or the man she loves so much, stop her from attaining her goals. Albrecht Schuch has an arguably even more challenging task of casting a major impression with a few delicate brushstrokes, which he does with aplomb.

A relationship drama, a story of resentment, power play, the pursuit of one’s passion, and sexual politics – all seen through the prism of the iron-fisted 1930’s Germany – Fabian: Going to the Dogs is a lot to digest. It takes a while to get going, or perhaps it just takes a while to get used to its peculiar look and rhythm. Some may find Graf’s complete and utter lack of reliance on historical drama tropes grating. I found the film’s energy, melancholy, and anarchic vibes refreshing, a 68-year-old master splattering paint over a well-worn genre.

"…feels both anachronistic and oddly fitting"