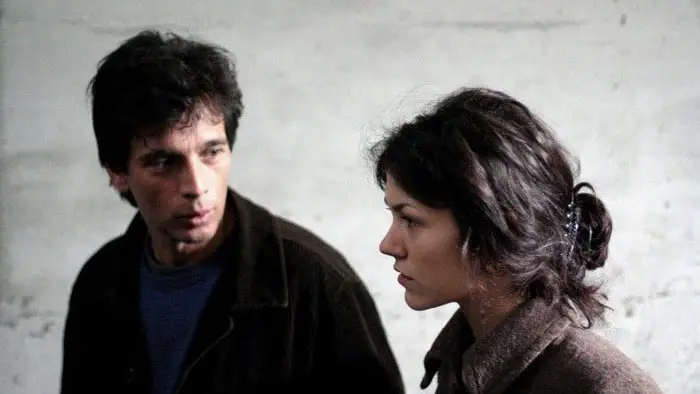

Mia Hansen-Love’s All Is Forgiven (Tout est pardonne) opens in Vienna in 1995 with toddler Pamela (Victoire Rousseau) playing dolls with her dad, Victor (Paul Blain). Victor is a poet who writes in the morning, takes long walks during the day, and does heroin at night. While Pamela bounces through her childhood, Victor’s habit starts to devour his relationships with her mother, Annette (Marie-Christine Friedrich), and reality. Moving to Paris, promising to clean up, Victor instead starts having needle parties with his drug pal Gisele (Olivia Ross). The ensuing wreckage eventually forces Annette to push Victor out, severing all connections between him and little Pamela.

The film then jumps ahead 11 years, where Pamela is now a teenager (Constance Rousseau), hanging with her buddies in Paris and doing normal teenage things. Her Aunt Martine (Carole Franck) secretly meets with Pamela to tell her Victor misses her and wants to see her again. She informs Marine she doesn’t remember anything about her father as she was too young when he left. Martine tells Pamela that Victor didn’t go but was thrown out, that he was very sorry and is clean now. Would Pamela like Martine to arrange a meeting to reunite her with her long-lost, heroin-loving father?

With All Is Forgiven, Hansen-Love immediately establishes a natural storytelling style, avoiding flashy lighting compositions and eschewing a musical score over the action, instead choosing diegetic songs. This allows for Cassavettes-like objectivity in which the audiences choose their reaction to the story instead of having it chosen for them. The director allows the characters to be presented how they see themselves, with Victor not understanding why he can’t relax with a bit of heroin now and then. Of course, there are clues to the filmmaker’s position, as seen in the repeated shots of parents with children in parks.

“Would Pamela like Martine to arrange a meeting to reunite her with her long-lost, heroin-loving father?”

Also, not criticizing Victor’s actions with melodramatic angles or angry horns blowing allows the narcotics to run their course and gives him enough rope to hang himself. Blain is wonderful, and you can really see him believing his own bullshit about how he has his habit under control. Friedrich does a perfect job of showing how much hurt Victor visits on everything. Hansen-Love’s brilliant choice of casting sisters as Pamela at different ages allows the viewer to understand that the same girl has lived two lives.

Much is made of the time jump, with some viewers upended that such a huge leap is done via a simple title card. However, considering the focus is the vanishing and reappearing of a drug fiend parent, it makes perfect sense, as Pamela was too young to remember how her father ruined her life the first time around. It also allows Victor a chance to do what many fiends do: use their absence to rewrite history as being simply misunderstood.

All Is Forgiven brings up an interesting question: If your life was wrecked as a little kid by a drug fiend and you were too young to remember it, was there any real harm done? While the treatment of Pamela’s reactions is a little too ambiguous, I was intrigued by the showcasing of the resilience of children. While Hansen-Love’s first work, the film is still a true accomplishment of raw emotion and engaging character observation.

"…a true accomplishment of raw emotion and engaging character observation."