Adapted from Stephanie Kallos’ 2015 novel of the same name, Language Arts tackles one family’s journey through the evolving narrative of Autism. It reminded me of a term I heard used on a podcast from one of my favorite film critics, Mark Kermode: neuro-divergent. It’s a phrase that can surmise the vast members found on the Autism spectrum whose minds merely process information in a fashion atypical to which we are accustomed.

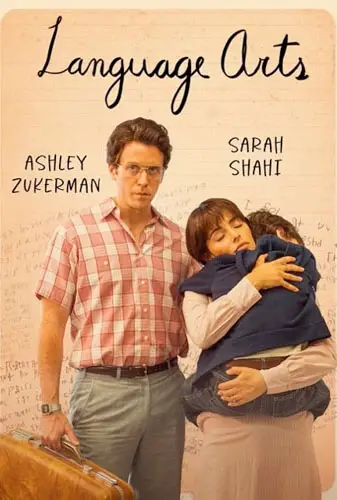

Written and directed by Cornelia Duryée, the film begins in 1993, as Charles (Ashley Zuckerman) and his wife Allison (Sarah Shahi) are re-evaluating their lives after years of recalibrating to suit the needs of their son, Cody (Kieran Walton). Years ago, they realized that Cody “lost his words,” which was particularly devastating to Charles, for whom, as an English teacher, words are invaluable.

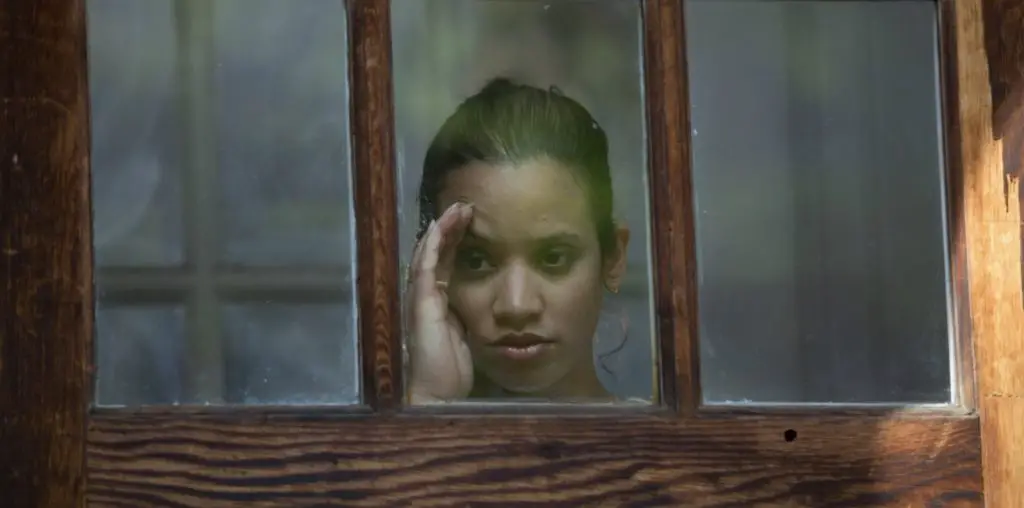

Language Arts then hopscotches through its narrative timeline, which can initially be jarring, but soon provides a broader context for all its characters, allowing us to see how past actions and precedents influence their current behavior. Charles, for example, appears solemn and standoffish, but we witness glimpses of his life as an awkward grade-schooler, which slowly pulls the curtain on his adult mannerisms. In the early 1960s, young Charlie (Elliott Smith) was a reticent student with a penchant for writing and one of the few who showed compassion for a classmate who was clearly on the spectrum.

At home, young Chalie would use writing as an escape from his highly dysfunctional home life with an alcoholic father and a materialistic mother. While effective in their own right, these scenes give meaning to the adult character, who is repressing childhood pain and using his silence as an emotional shield.

ELLIOT SMITH as YOUNG CHARLIE MARLOW in the film “Language Arts” – PHOTO CREDIT: Annabel Clark

“…re-evaluating their lives after years of recalibrating to suit the needs of their son…”

The story of Language Arts is relatable for any whose lives have been affected by Autism, but the compassion demonstrated by the filmmaker, who approaches the subject with compassion and heart. This helps the film blossom into something more than a “dealing” with Autism narrative. Instead, it is about how people connect (and separate) based on the bonds they form through life’s circumstances.

The film features actors portraying the various mannerisms associated with those on the spectrum, which could easily have come off as pandering and offensive, but is demonstrated with care and respect for its characters. As a result, we become invested in their lives and well-being. Zuckerman’s nuanced performance slowly reveals the roots of his pain and sadness, while Shahi remains resolute and determined throughout. She shows moments of self-doubt with her decisions but remains steadfast with her choices for the betterment of her son.

As the young Charles, Elliott Smith is heartbreaking. His flinches at loud noises and thousand-mile stares at home reveal more than any monologue ever could. Yet it’s the remarkable, humane performance of Lincoln Lambert as Dana, young Chalie’s autistic classroom friend, that is the crown jewel. His sweet, carefully modulated performance is equally compassionate and moving.

Without steering into treacle, Language Arts demonstrates that acceptance of others can prove a challenge even for those with the noblest intentions. However, Duryée equally shows that empathy and love can arise from some of the most unexpected places.

"…demonstrates that acceptance of others can prove a challenge even for those with the noblest intentions."

[…] post Language Arts first appeared on Film […]