Monte Hellman hardly merits an introduction. My words cannot do him justice. No aspiring director should be allowed to pick up a movie camera without seeing TWO-LANE BLACKTOP. If you don’t know that film, shame on you. And shame on me for not owning the DVD.

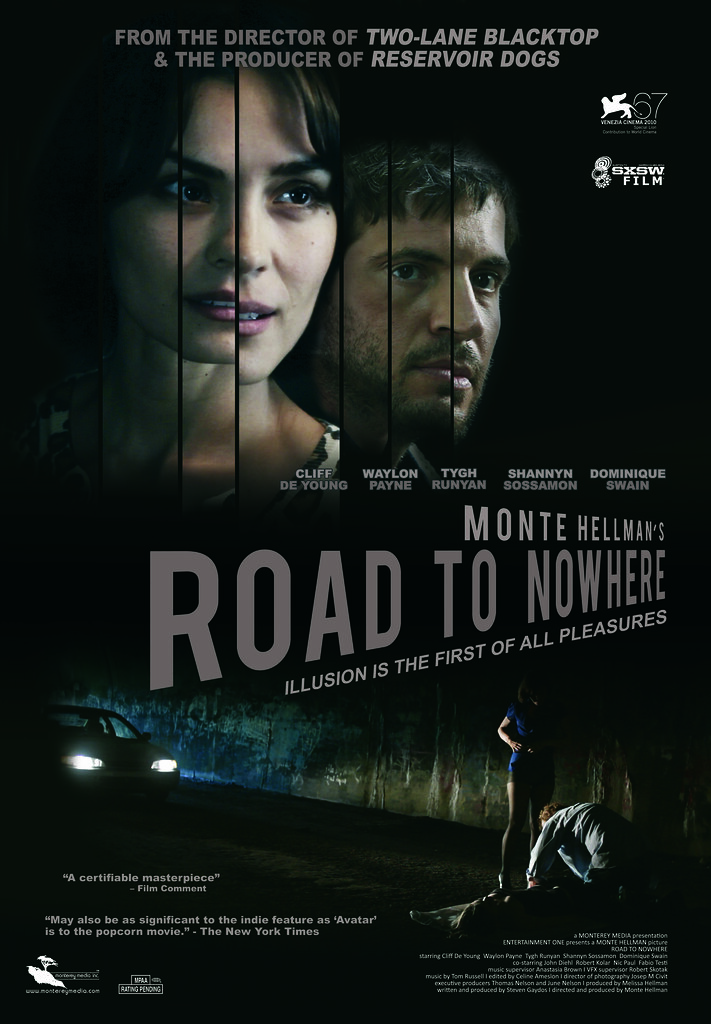

That Hellman just premiered his first film in 20 years got many tongues wagging in the cinephile community. A lot of cynics told me ROAD TO NOWHERE couldn’t be as good as people said it was. I saw the film last night after this interview and let the record reflect it is that good. While enigmatic as anything Lynch ever shot, its relaxed pacing and subdued direction liberate the film from stylized gimmickry and make its labyrinthine storyline all the more disturbing. ROAD TO NOWHERE will supply grist to the film theory mill for the next half-century.

As for the auteur’s own interpretation, Monte is keeping a poker face. As he said during the Q&A about the film: No Apologies. No Explanations. And, most importantly, NO REFUNDS. That said, he is very approachable and has a quick trigger finger on the e-mail “send” button.

For those not lucky enough to have seen the premiere of ROAD TO NOWHERE in Venice last year, tell us about the new film… in your own words.

ROAD TO NOWHERE is a magical movie. Every other movie that I’ve done has been a conscious act of creation. ROAD TO NOWHERE let me know early on that it had a mind of its own. It caused actors to withdraw from the project — or me to fire them — when they weren’t the actors IT wanted. It forced me to shoot additional takes that completely altered the meaning of the movie. It constantly changes into new shapes and forms at each projection so that I’m continuously discovering new movies I hadn’t seen before. I can’t say that I’m afraid, but I’m certainly careful.

The famous closing shot of TWO-LANE BLACKTOP involves a frame of film melting in the gate of a projector. What does that image represent to you? Does it have anything to do with laying bare the artifice of film as material (i.e. celluloid) as opposed to the cinematic illusion of moving pictures?

It certainly recognizes the material going through the gate, but it’s not about that material. I was initially resistant to the idea because I thought it was too intellectual, the reference to the speed of film moving through a projector. But when I imagined it, I was moved. So against the advice of many of my collaborators, I decided to go for it. And I’m still moved by it, so I have no regrets.

I think it’s historically short-sighted to romanticize film as an integral part of photography. It was merely one stage in a long process of development. Before film there was glass plates. Film itself was both a chemical and physical process at different stages. Now we have digital imaging. I’m sure someone is already at work on whatever it will be to replace it.

You’ve worked mostly outside of the studio system. Do you think it is easier to make an independent film today or in 1961?

It was easier in 1961 because for me at that time it only depended on a decision by one person. Now there are readers, studio executives, production company development persons, producers and executives, and/or multiple groups of investors.

Looking back over your career in film, what is your greatest regret?

That I allowed my agents and lawyers to prevent me making FAT CITY.

If you had unlimited resources and artistic freedom, describe the film you would most like to direct.

I now insist on artistic freedom, which I sometimes had to obtain through political means before, and I never worry about resources. I believe any movie can be made for any budget if you have the will to make it. So the film I want to make now is the next one on my plate, one I’ve been trying to make for some time. I probably have others that are even dearer to my heart, but I’ve put them aside because I don’t feel the time is right for them. The one I plan to make now is a supernatural romantic anti-terrorist thriller called LOVE OR DIE.

Sounds interesting. Could you tell us a little bit more about LOVE OR DIE?

It’s a “ticking clock” time-bomb thriller about two people who are murdered who fall in love after death, and are given a chance to go back to life and live out their lives together if they can prove they’re still in love after 24 hours.