The 1925 silent film “The Phantom of the Opera” starring Lon Chaney stands as the best argument against remaking classics. Since its release, there have been five official remakes (a sixth, based on the Andrew Lloyd Weber musical, is currently in the works) which brought to the screen everything that the original lacked: color, music, a higher level of sadistic violence, and more sophisticated special effects. But none of these remakes came close to capturing the genuine sense of horror in the original version, which is widely regarded as being among the finest films ever created.

Yet “The Phantom of the Opera” itself has come down through the years rather worse for the wear. The problems began four years after its release, when Universal Pictures decided to cut 10 minutes from the footage and add new footage (including a prologue with a weird man holding a lantern in a dark catacomb) plus a new soundtrack that would take advantage of the new push to talking pictures. One major problem with this was the absence of Lon Chaney, who was then under contract at MGM and could not add his voice to the film. The solution, if you could call it that, was to leave the Phantom’s voice off the soundtrack. Inexplicably, the soundtrack was lost over time yet this reissued version became the accepted standard version. The 1925 version survived, but the extant prints deteriorated to the point that they were rarely screened; many scholars mistakenly believed this version was lost. In 1953, Universal stupidly neglected to renew the film’s copyright and “The Phantom of the Opera” lapsed into the public domain, resulting in a flood of badly duped prints that became commonly seen on TV broadcasts and cheap videos.

This new DVD release presents the ultimate treat for “Phantom” fans by offering both the 1925 and 1929 versions. The latter has been fully and lovingly restored, while the battered 1925 is presented here in the best quality print known to date (which is very watchable, given its history). Quite frankly, both versions are more than adequate in serving up the classic chills and creeps in this wonderfully eerie tale and it is a major event to finally enjoy this film in the pristine visual presentation it deserves.

So much has been written about this film that additional commentary may seem like a waste. Still, some points that are often overlooked need to be stressed. Perhaps the most satisfying aspect of the 1925 version, compared to the endless remakes and ripoffs (including the hi-fi “Phantom of the Paradise”), is the Phantom here is presented as Gaston Leroux envisioned him in the original novel: as a demented freak with extraordinary musical genius. The subsequent versions recast the Phantom as a kindly composer who was cruelly disfigured after his music is stolen and who is driven to homicidal depths. This revision of the Leroux text makes the later Phantoms seem like bitter men out for much-deserved revenge against their tormentors. Chaney’s Phantom, in comparison, is a genuine physical and emotional monster, which actually makes his love-pangs and suffering for the soprano Christine (a rather diffident Mary Philbin) seem all the more gut wrenching. Chaney’s Phantom does not rediscover a stolen humanity, but unexpectedly taps into a dormant humanity that he is unable to manage.

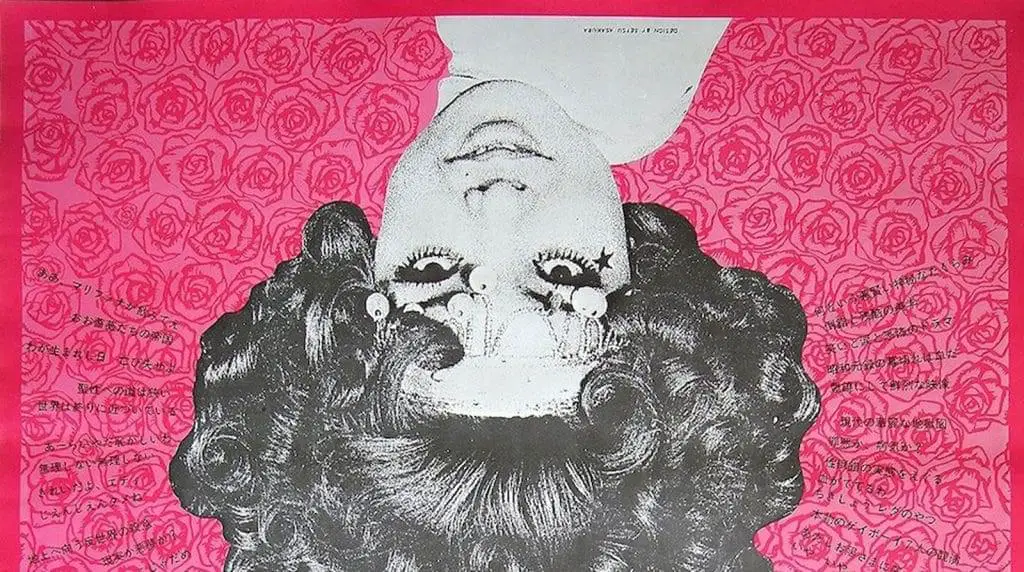

The famed unmasking of Chaney’s Phantom by Christine while he is playing the organ actually comes much earlier in the silent version than in the subsequent versions, which kept the Phantom’s mutilated face covered until the final moments (the Lloyd Weber musical puts the unmasking back to its earlier place in the plot). While much as been written on Chaney’s extraordinary self-designed and self-applied make-up job, what should be noted is the manner in which the unmasking scene is shot. This is the rare film where a character looks straight into the camera without intentionally cuing the audience that the proverbial fourth wall is down (such as Bob Hope’s asides to the audience in the Road pictures). The Phantom reacts in horror that his mask has been ripped off by Christine, who is behind him and is clueless to his appearance. Chaney’s eyes widen and his mouth gasps in terror when Christine’s curiosity exposes his deformity–one can feel the sense of violation which immediately infects him. The head-on, literally in-your-face presentation of the Phantom’s appearance horrified the less sophisticated audiences of the 1920s (some people reportedly fainted when the film was screened), and it is inevitable that Christine will be horrified by what she is to witness when the Phantom rises and turns around to show himself. But the concept of having the Phantom share in the terror of his appearance is a point of subtle intelligence that many people never quite grasp.

The one thing missing from the 1925 version of “The Phantom of the Opera” is, of course, opera. After all, this is a silent movie. The subsequent remakes put in plenty of opera (the 1943 version put in way too much, with booming Nelson Eddy actually taking star billing over Claude Rains’ Phantom). The 1929 sound reissue incorporated new opera footage to take advantage of the film world’s liberation from silence, though ultimately that effort cannot be appreciated since the soundtrack disappeared years ago. Yet the idea of a silent movie with an opera house setting should not be considered too strange, since there were several silent film versions of celebrated operas including “Carmen” (with Metropolitan Opera diva Geraldine Ferrar), “Thaïs,” “La Boheme,” “The Merry Widow” and “Madama Butterfly.” Silent movie opera? We’ll leave you that one to ponder.

Disagree with this review? Think you can write a better one? Go right ahead in Film Threat’s BACK TALK section! Click here>>>