How far into someone else’s world can a person go before a person finds himself lost? What doors are opened that perhaps should not have been? What happens when a person wants to leave but cannot? Nicholas Garrigan (James McAvoy), one of two major characters in Kevin Macdonald’s film “The Last King of Scotland,” knows very well the consequences of entering a stranger’s territory and venturing in too deep. Inspired by the life of Idi Amin, Uganda’s dictator in the 1970s, “The Last King of Scotland” follows Nick Garrigan’s experiences as he becomes entangled in the private and public worlds of Ugandan politics.

Macdonald’s film begins by introducing the viewer to Garrigan, a Scottish lad who has just graduated from medical school. He has dinner with his mother and father to celebrate the occasion and to mark the beginning of what could be a very uneventful life as a family doctor. Garrigan will not let the prospect of such dullness zap his young adult years dry. He takes a globe, spins it, and vows to go wherever his finger lands: Canada—which doesn’t count, so he spins it again. Uganda. Chance (or fate) brings him to a country that is dealing with decolonization and a new government under Idi Amin.

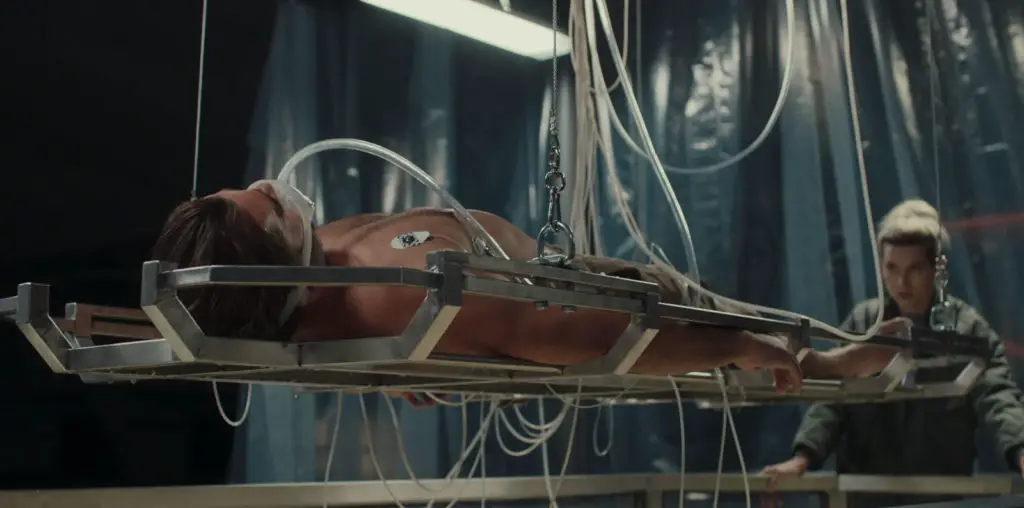

Garrigan works at a rural clinic run by Sarah Merrit (Gillian Anderson) and her husband (Adam Kotz) until an encounter with Amin lands Garrigan the post of personal physician. The Scotsman quickly becomes fascinated by the intimidating but charismatic leader of the new Uganda. As Amin’s physician, he is granted tremendous access to information as well as the man himself. Garrigan gets to know him from such a privileged point-of-view that it is nearly too late when he realizes just how far into the heart of Amin’s realm he has treaded. Amin is not just a patient; he is a man who can make people disappear.

With ethnographic-like imagery reminiscent of French documentary filmmaker Jean Rouch’s film “Jaguar” (1967), “The Last King of Scotland” doesn’t just present the unlikely friendship and father-son relationship that develops between two people of very different backgrounds. “The Last King of Scotland” is as much about the Ugandan dictator as a historical figure as it is about Nick Garrigan, a signifier of the white “Other.” Without lecturing too much, the film suggests that Garrigan is just like all the other citizens of the British Empire—all conquest and no concern. The viewer knows, however, that such an attitude does not apply to the Scottish doctor. He may have to take responsibility for some of what happens to him, but viewer identification with him is strong throughout, especially after Garrigan has learned the many lessons that Uganda teaches him. The Scotsman wanted excitement and adventure, and he gets a triple dose of it by the film’s end.

In addition to a very engaging script, Forrest Whitaker and James McAvoy amazingly express the tension and the camaraderie shared by Amin and Garrigan. Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle expertly highlights the volatility of their interactions in certain scenes through close-ups and hand-held camerawork. “The Last King of Scotland” ends with footage of the real Idi Amin, a man whose kingdom a person could very likely choose to enter and then leave beaten but alive or not at all. The juxtaposition between the jubilant music and the end titles that inform the viewer that Amin’s regime had killed 300,000 of his own people is somewhat unnerving but nonetheless powerful.