In terms of commercial timing, the new film adaptation of the controversial John Adams opera “The Death of Klinghoffer” could not have come at a worse time. As interpreted by British filmmaker Penny Woolcock, “The Death of Klinghoffer” is an unashamedly pro-Palestinian and virulently anti-Israeli (and, unspoken but clearly implied, anti-American) creation. Yet “The Death of Klinghoffer” is also a profoundly disturbing work which dares to grab at the least commercially viable aspects of the film medium and tie them together into a richly textured and intellectually jolting creation. If this film is allowed to be shown widely, it could easily become the most hotly-discussed and dissected production of the year.

“The Death of Klinghoffer” first debuted as an operatic production in 1991 and was almost immediately greeted with condemnation from many corners. The primary complaint was using the hideous real-life events at the core of the plot, the 1985 hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro by Palestinian terrorists and the execution of wheelchair-bound American Leon Klinghoffer during the siege, as a platform to inveigh against Israeli policies in the Occupied Territories–as if the hijacking and murder were, in some way, justified to avenge for years of Israeli repression and brutality against Palestinians. Oddly enough, some complaints on the opera came from those who saw it as pro-Zionist.

The film version of “The Death of Klinghoffer” will not be confused with the Zionist cause. Certainly not in the opening sequences, a black-and-white recreation of the May 1948 eviction of Palestinians from their homes by gun-toting members of the militia in the newly-created State of Israel. One Palestinian family is forced out at gunpoint with only the clothing on their backs by a rifle-toting Israeli who later claims the now-empty home for himself. His first action in this stolen property: taking a woman (it is not certain if it is his wife or sweetie) and making love on the bed left behind by the evicted and now-exiled family.

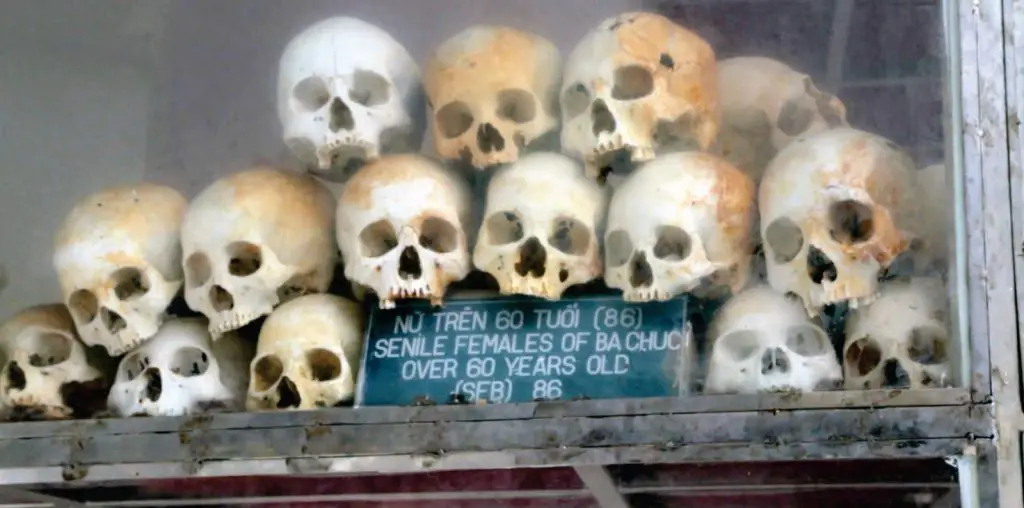

Throughout “The Death of Klinghoffer,” Israelis are depicted in a harsh and unforgiving manner. Woolcock spins a sharp historic overview of the region’s history by juxtaposing newsreel footage of Nazi stormtroopers emptying the Jewish ghettoes of wartime Europe with scenes of Israeli army personnel opening fire in Palestinian refugee camps. A mass grave from a 1945 concentration camp is balanced against a mass grave from the 1982 slaughter at the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps. Equating Israelis with Nazis will certainly and deservedly brand this film as Palestinian propaganda, but “The Death of Klinghoffer” has so many gaping holes in its recollection of what transpired since 1948 (including no mention of how Egypt and Jordan stole the land set aside by the United Nations for a Palestinian state) that it would never be able to seriously stand up as a proper presentation of Middle East history. Even when presented with an opportunity that shows unmitigated Palestinian sadism (when a woman who refuses to wear a hejab is stoned and disfigured with acid by a crowd of men) offers a weak mea culpa by stating this is the result of Islamic fundamentalism rooted in despair; the fact the Koran specifically does not condone misogynist acts of violence is never raised, nor is the bloody toll of Palestinian terrorism during the past several decades ever mentioned. (For the record, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, the spiritual leader of the Palestinians during the 1940s, was an open supporter of the Nazi cause.)

But where the productions fails as an honest record of the roots of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it rises as a vibrant experiment in striking a union between opera and cinema. Unlike many opera films which are heavily theatrical in their presentation, “The Death of Klinghoffer” is shot in the manner of a cinema verite docudrama. At first it seems incongruous to offer realistic location shooting (not to mention violent political situations) where the characters converse via operatic singing, but as the film unreels this unlikely mix clicks into its groove. Indeed, the film’s occasional breaks into straight dialogue (mostly from an unruffled British newscaster providing updates on the Achille Lauro hijacking) seem totally surreal compared to the rest of the soundtrack.

Unlike other opera films, “The Death of Klinghoffer” tries very hard to remove all traces of operatic acting. By opting for a neo-realistic style of acting, the film succeeds in polishing the abrasive agitprop edges of Alice Goodman’s libretto and almost gives a humanizing spin to the deeply flawed mix of characters gathered here: the terrorists who alternate between bravado and unease over their gun-toting power, the ship captain’s whose attempts at diplomacy and reason ultimately prove impotent, an elderly Austrian passenger who remains hidden in her cabin’s bathroom with a basket of fruit throughout the entire ordeal, and a British showgirl among the ship’s hostages who unexpectedly hams it up for the news cameras after the hijacking is over. Thanks to the ensemble cast, who are in fine voice and look quite good on camera (particularly Christopher Maltman’s captain, Leigh Melrose’s macho terrorist Rambo and Kirsten Blase’s showgirl), this is an operatic experience that benefits both eyes and ears.

Strangely, the character of Leon Klinghoffer doesn’t quite fit the mix. Part of the problem clearly comes from the Goodman libretto, which makes the wheelchair-bound American something of a pompous bore in his arguments with his captors. And part of it may be Sanford Sylan’s weak performance, which is not allowed to tap into the humanity of the man. But director Woolcock strangely pushes the envelope here after Klinghoffer is assassinated and thrown overboard: for several minutes, the camera follows the murdered man’s body as is sinks under the sea, unleashing a flood of pearly white air bubbles while it descends to the watery depths. It is a credit to Sylvan for maintaining the stillness of death during these underwater sequences, but the extended length of this segment becomes tasteless very quickly. From an artistic standpoint, this is the film’s biggest and ugliest mistake.

“The Death of Klinghoffer” is not an easy film for many people to endure, from both an aesthetic and geo-political level. Yet at a time when so much film output feels formulaic and quotidian, the audacity and gutter-level rudeness of this production comes as a shock to the system. And for those who know how to respond to such shocks, “The Death of Klinghoffer” can be a much-welcomed challenge.