A minor chapter in the history of domestic terrorism gets the feature-film treatment, to decidedly mixed results, in “The Assassination of Richard Nixon.” Sean Penn plays the mostly forgotten Samuel Bicke, a man who, having come to the end of his quite frayed rope in 1974, tries to hijack a jetliner and fly it into the White House in an attempt to kill Nixon. He failed, of course, but the film isn’t really so much about the hijacking itself – a brave choice, considering how many parallels the filmmakers could have tried to draw with 9/11 – as it is about a put-upon furniture salesman and the unraveling of his life.

Sean Penn plays Bicke, a sad-sack furniture salesman in Baltimore, circa 1974. We get glimpses of his previous life, the little house that he shared with his kids and his wife, Marie (Naomi Watts, trying so hard to look just as disheveled as she did with Penn in “21 Grams”), and the tire business that he used to work in with his brother, Julius (Michael Wincott). Bicke is an utter incompetent when it comes to living in a society, a mumbly and consistently inconsistent malcontent destined to get himself fired from one job after the next. By the time the film introduces us to Bicke, his wife is fed up, ready to make their separation into a divorce, his brother wants to wash his hands of him, and his only friend is a mechanic, Bonny Simmons (Don Cheadle), who will find good reason to regret this relationship by the end of the film.

Frustrated at his inability to make any sort of solid life for himself – his one idea at starting a business appears childishly inept – Bicke turns his anger at distant targets. Upset by pervasive racism, he makes a random visit to the local Black Panther office, where a bemused Mykelti Williamson takes Bicke’s donation after listening to an awkwardly stammered explanation of why white people need to do more. But mostly Bicke is angry at the president, whom he sees as emblematic of how society crushes the little guy (i.e., him). These thoughts he relates in long tape recordings that he addresses to Leonard Bernstein, whose music he loves. Determined to make a difference, and just get some attention, Bicke’s thinking turns to killing the president, fantasizing and planning while his behavior becomes increasingly erratic and full-on dementia looms. While much of the material here involving Bicke’s relationships seem to have been dramatized for the film, the basic details that make up the story of his insanity are true.

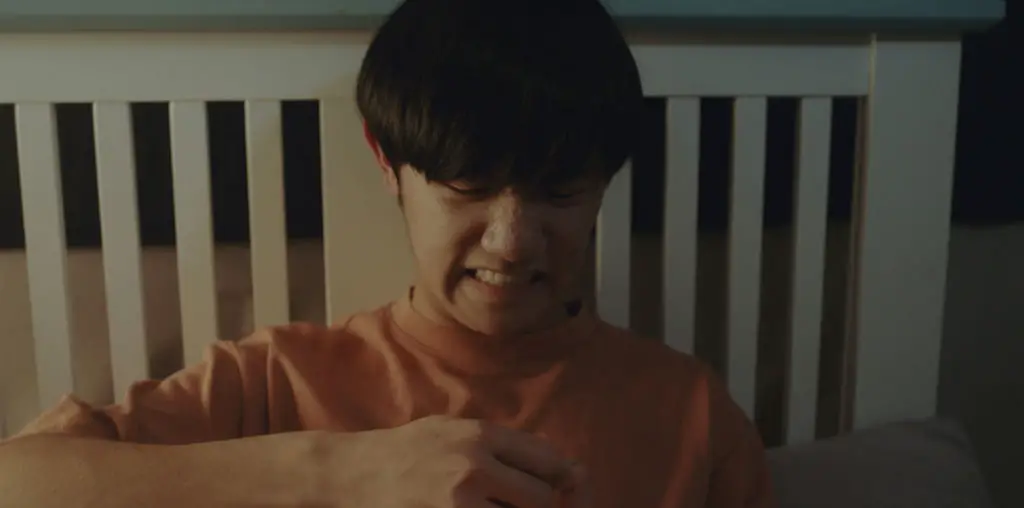

The primary problem with “The Assassination of Richard Nixon” comes in its attempts to make drama out of a minor man’s minor stab at infamy. While the film commendably refuses to try and elicit sympathy for Bicke (this is a man who dug his own, quite deep, grave) , it is never quite able to mold him into an interesting character. He’s such an obvious wreck that not only do we understand why everyone in his life walks away from him, but it seems utterly inconceivable that his boss at the furniture store even gives him a job. Many will see in Bicke’s antisocial tendencies and his stunning eruption into needless violence at the end (a truly horrifying conclusion, constructed with icy precision) more than a few echoes of De Niro and “Taxi Driver.” But charges of mimickery would be misplaced, as De Niro’s Travis Bickle was, though fictional, obviously inspired by the spate of lone psychopaths who cropped up throughout the 1970s, like Bicke.

Fine performances aside (especially from Penn and Cheadle, who establish a warm rapport that’s the only island of humanity here), this is too hermetic and sealed-off a film to really elicit much reaction in the end besides a mute sort of sadness. Which, given the pathetic spectacle of Bicke’s wasted life, may be appropriate.