Auteur director Steven Soderbergh and veteran writer David Koepp have devised Presence as if from the most metaphysical reaches of their craft. Thematically alchemical and technically freeform, Presence is more a vision than a film. But there is a delicacy to that vision — an intellectual litheness that transfixes like a syringe and, scene by scene, delivers a nostalgia that aches in the subconscious. You don’t watch Presence, you feel it watching you.

After moving into a new home, a seemingly ordinary family becomes aware of an otherworldly entity already residing there. As everyday life becomes strained, hidden resentments between the parents Rebekah (Luci Liu) and Chris (Chris Sullivan) begin to reveal themselves, fraying the family’s tenuous veneer.

Presence marks a noteworthy return to small-scale filmmaking for both Soderbergh and Koepp. It’s been 34 years since Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape won him Roger Ebert’s praise as the “Poster boy of the Sundance generation.” And it’s been two decades since Koepp’s pen held him at the crown of Hollywood in the early-2000s. This history is apt, as the intimate scope of Presence — principal photography lasting a mere 11 days and a total budget of only $2 million — has liberated both director and writer. Free from the distractions of a modern blockbuster, Presence sees both men at their most deliberate, articulate, literary, and sumptuously nuanced in years.

“…assembled together like fragile vignettes to present the image of a hopeful, broken, and fundamentally real family.”

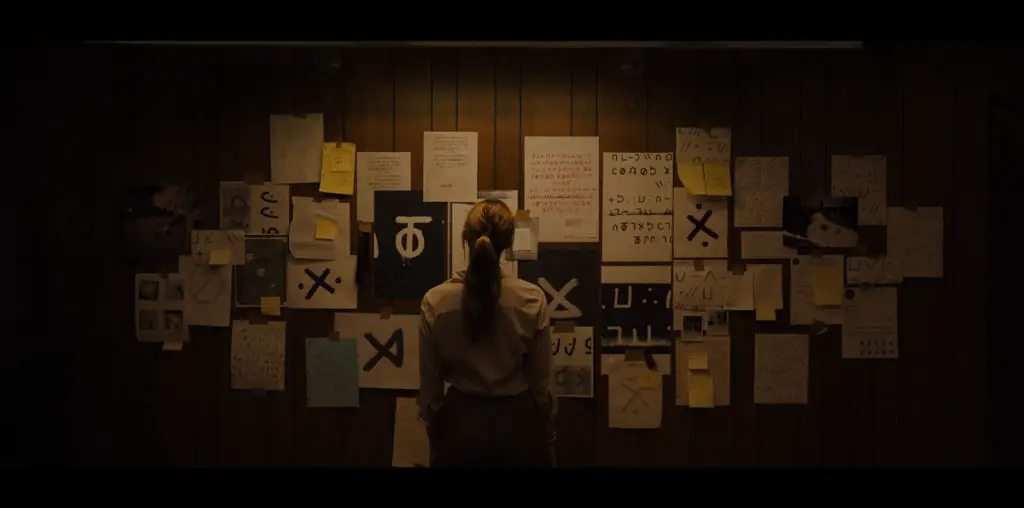

From a technical standpoint, the camera work is as meticulous as it is hypnotic. Soderbergh’s lens floats through the space with balletic sensibility, framing the characters with choreographed precision. Koepp’s script is similarly dreamlike. Scenes proceed like memories, revealing layers of emotion to the characters and the family. The marriage of story and camera is a marvel throughout Presence. The two aspects inform each other both proactively and retroactively as if to be studied. Benign interactions develop and expand, later returning to disclose secrets both narrative and symbolic. It is a deft experimental dance between director and writer, in turns whimsical and eerie, all leading to a finale that is utterly haunting in its revelation.

Still, Presence is not an immaculate experiment. Select moments in the midsection come across as exaggerated, almost silly, especially in comparison to the rest of the film. And key pieces of dialogue are likewise artificial, existing only for the sake of exposition. But these weaknesses are fleeting and, at a clean 84-minute runtime, easy to forgive. They in no way sully the oneness of the vision.

And, indeed, Presence’s great strength is not in the exquisiteness of its detail but in its quietness, its delicate vision. Both Soderbergh and Koepp are taking their time to cultivate a precise and pure sentiment that animates the film. The characters are tangible. Their emotion is palpable. Every shot is a moment of their lives, assembled together like fragile vignettes to present the image of a hopeful, broken, and fundamentally real family. Soderbergh and Koepp have melded form and myth as only two adepts could. With Presence, you feel them watching you, too.

"…You don't watch Presence, you feel it watching you."