“An actor projects himself. The movement is from the inside out. In a film, it’s the opposite. Everything must be within. Nothing most escape.”- Robert Bresson

“A film should be something that is continuously being reborn.” – Bresson

The Criterion School of Cinema is a continuously miraculous, almost religious form of filmic education which has required only a DVD player, TV, and a wide-open canyon-like mind. Through 327 teachers by March 2006, ranging from the French New Wave to Italian neo-realism and relatively recent works like “Traffic”, it presents classes in history, philosophy, and filmmaking technique, even reaching the technical side of the artform. After #314, “Pickpocket”, I wonder why the heck I haven’t returned to this side of DVDs earlier. Certainly Warner Bros. has earned its reputation as being second to Criterion, but here is an experience that is always above words, despite the makeup of it always containing thousands upon thousands of syllables and hundreds of thoughts. Robert Bresson’s quote about the rebirth of films indirectly foresaw The Criterion Collection, and “Pickpocket” has received quite a treatment.

I believe Bresson would approve of Criterion’s efforts, as all possible interpretations of “Pickpocket” are spread throughout the very special features of this disc. But first, my own. Admittedly, I have not yet schooled myself deeply in the ways and methods of Bresson. A few of his movies are still deeply buried in an insanely enormous Netflix queue. But “Pickpocket” is an exceptional surprise. I’ve harbored a hope that with every movie I see, it affects me. No matter if the action is cartoonish or the material satirical, it has to click, present itself as actually trying to move me either to laughter or solemn emotion. Even chills and tears have happened through many movies. After all, that’s one of the major reasons movies are seen everyday by millions of people. Entertainment, yes, but to be affected, to feel the lives of different people, that’s also a great reward and certainly for any filmmaker too if audiences connect with their movie. Another desire is also to supply my own emotions, to be an active participant in a movie that way. “Pickpocket” supplies both the former and the latter. In this story of Michel (Martin LaSalle), a pickpocket who plies his trade for whatever reason you wish, the faces of Bresson’s imagination are blank. They’re distinguishable only to us, but put them in a crowd and they’re gone.

Why does Michel do it? Love? Perhaps. Love of the act, excitement that can’t be had from a regular day’s work like anyone else who might pass by him unnoticed, unless that person is his next victim. A desire for money is the sticking point in talking about Michel because he doesn’t seem like the type to buy new suits or anything else that would better his dingy, prison-like apartment. He is also young, perhaps unsure about what to do in a society that seems to do everything, but does it without feeling. In fact, when he joins two accomplices (Kassagi and Pierre Étaix) to pickpocket a few people aboard a train, it is stunning that the victims don’t even notice their money or watches missing, or even feel the act taking place. Perhaps the victims are less attuned to the sights and sounds around them than he is.

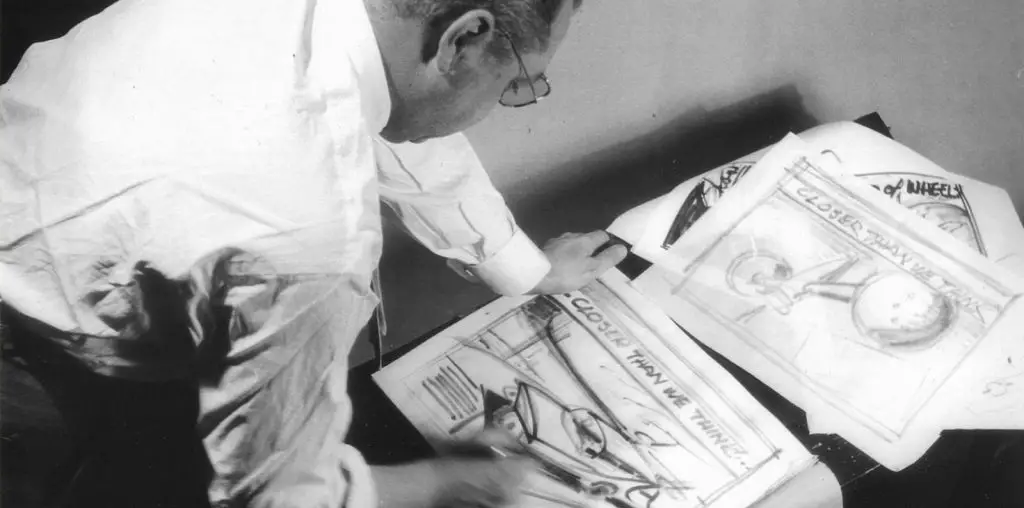

The questions over Michel aren’t the only ones to be mulled over. As in Dosotoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, there is a woman (Marika Green) who may prove to be salvation to Michel, turning him away from the life he embraces. Michel’s friend Jacques (Pierre Leymarie) represents further honesty, the career side, in giving Michel some names to pursue for work. Marika Green, 16 years old at the time, is the pre-Natalie Portman, exhibiting the same qualities Portman has today, the same look of ethereal beauty that triggers curiosity, wanting to listen to what she has to say, besides simply admiring her looks, for the sake of knowing more about her. Michel also contends with a police inspector (Jean Pélégri) who’s interested in him for the obvious lawful reasons. Pickpockets cannot slink through the streets, snaking out people’s money like a handkerchief, and he tries to figure out Michel, listening to his theories on thieves, but it doesn’t go anywhere. A memorable face in Bresson’s museum of faces is Kassagi, credited only by last name. He’s hardened by experience, quiet, quick about the job and very skilled. In fact, according to the concentrated, educated voice of James Quandt on the audio commentary, Kassagi was credited as such so any authorities watching wouldn’t recognize the name. He also loved lifting the wallets from the four policemen who were present during a complicated sequence of the movie and shocked them when he returned their wallets. Fortunately, Kassagi’s skills are on display outside of the movie in an episode of what appeared to be an amusing French television show in which he performed sleight-of-hand tricks and lifted many wallets and watches at the same time. In fact, with how quickly Kassagi performs his act, it is a true testament to a most amazing set of skills as he not only can switch from one part of his act to another, but with his quick words throughout, he knew how to entertain. Make them laugh, and any pocket can be picked.

Just as remarkable as “Pickpocket” is the journey of the three main actors, in a documentary from 2003, “The Models of Pickpocket” by the elegant-minded Babette Mangolte who is not only intent on interviewing Leymarie, Green, and LaSalle, but also focuses on certain aspects of their world with her camera, defining who they are outside of their words, what they have become after all these years. Leymarie talks of 40 takes for him to climb the staircase, and explains how Bresson wanted to wear down the actors, to bring out from them an emotion not seen in the first take. As Green explains, Bresson wouldn’t even give any reason for another take. He’d just call it and they’d do it again. We, in turn, are given a most exquisite treasure, actors honest about a director, a full portrait of Bresson from their perspectives. Bresson himself is given about six minutes in an interview from a French television show called Cinépanorama in which the militaristic-looking interviewers simply sit down after Bresson has been seated and start asking their questions. There are no pretensions, no grand scheme. In fact, they spend two of the questions arguing for the audiences, in what they might want to see, and Bresson defends his view that he’s not turning his back on those expectations. This interview proves that no matter what it takes for any title, Criterion scours the Earth for anything of value. Bresson is quiet, well-spoken, confident in his views, and never wavering. Couple that with a Q&A featuring Marika Green and two French filmmakers after a screening of “Pickpocket” in which the filmmakers explain the influences of Bresson on them, and Paul Schrader’s marvelous 14-minute introduction explaining Bresson’s influence on him as well as the meaning of Bresson’s work, and this is a fascinating, masterly education which compels any viewer to hunger for more knowledge after they have learned whatever it is they want to learn. Whether it’s how the pickpocketing was done, or Bresson’s filmmaking methods, or analysis of the characters (Quandt’s commentary covers every possible angle from religious to psychosexual), this Criterion school is open to the intrepid lovers and curiosity seekers of the movies. Embrace it and enjoy!