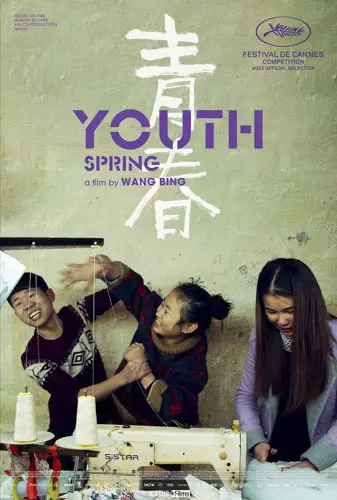

NOW ON VOD! “Made in China.” A simple phrase we see stamped on the bottom of plastic toys, welded into heavy machinery, and, of course, adorning the tags of our clothing. The phrase might get a rise out of a politician or an activist and prompt a debate about American jobs being moved overseas or poor working conditions, but how often do we think of, or much less see, those in China producing all those lovely things for us? Youth (Spring) shows us the intimate lives of those workers.

Filmed over the course of five years, the documentary takes a thorough look at workers in various textile facilities in the Chinese manufacturing town of Zhili. As the film’s name would imply, these workers are young, often in their twenties, but some are as adolescent as sixteen. They often come from rural parts of the country to make money, living in tight dormitories and less-than-ideal conditions. Some come to make enough to chase their dreams or plan for the future. One young woman comes because she is pregnant and is saving for either a wedding or an abortion, as her parents, her boyfriend, his parents, and finally her decide what to do.

“…a thorough look at workers in various textile facilities in the Chinese manufacturing town of Zhili.”

She’s just one of a massive cast of characters we come to meet over the course of the film’s three-and-a-half-hour-plus runtime. Much of that time is spent following these youths in their day-to-day lives as they work and interact with each other. In many ways, it works like a documentary companion piece to Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, as both follow the monotony and frequently slow-paced day-to-day lives of their protagonists. A good chunk of Youth (Spring) is devoted to following people simply walking from one place to another in an unbroken shot as they interact with others and observe the world surrounding them. Other times, a camera will linger on a pair of people having a long (often flirtatious) conversation.

The immense length and repetitive format can sometimes make the film feel like an endurance test. To say that its pacing is glacial would be unfair to the melting ice caps. There isn’t much to engage the audience with extremely limited explanatory text, no voice-over, and even an absence of non-diegetic music. The filmmakers are seemingly not interested in telling a particular story or promoting a specific narrative. Rather, they want to put the audience in the shoes of the people who inhabit these factories and tell their very human stories. For two hundred and twelve minutes, we become a fly on the wall watching as these young people work in sweatshops, form connections, bicker, head home to see their family, fight for fair pay, and do nothing at all for a good chunk of the runtime.

Youth (Spring), which had its premiere and competed at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, is the first in a planned trilogy from documentarian Wang Bing. All told, Wang estimates the three films are planned to follow the same cast for an astounding total of nine hours and forty minutes. At the very least, it will be shorter and more kinetic than Charlie Shackleton’s ten-hour-long “documentary” Paint Drying.

That film, however, was made as a way to torment a ratings board; this was meant as, if not exactly entertainment, a piece of art to connect viewers to people half a world away. So, is it worth the portion of your day you’ll devote to it? I suppose it depends on how much you enjoy unbroken shots of people walking up and down stairs.

"…Other times a camera will linger on a pair of people having a long (often flirtatious) conversation."