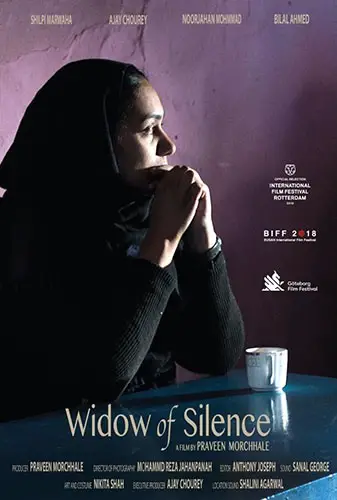

It takes an artist of great skill to make the mundane resonant, to speak volumes with a brushstroke. Like his Belgian counterparts, the Dardenne brothers, Indian filmmaker Praveen Morchhale deftly chronicles the plights of those shunned by society. Seemingly simple, minimalist narratives gain tremendous depth as they progress, revealing existential/sociopolitical/spiritual undercurrents that linger in the mind long after the silent credits roll. In Morchhale’s debut, Barefoot to Goa, a children’s journey to reunite with their grandmother became a parable about loneliness and death. Similarly, a broken chair morphed into a coming-of-age symbol in his follow-up, Walking with the Wind. With his third feature, the tragic Widow of Silence, Morchhale firmly establishes himself as the leader of the Indian New Wave.

It takes patience to sit through Widow of Silence’s slim running time. Morchhale is not out to entertain. With splendid assistance from cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah, the filmmaker immerses his viewer into a milieu both relentlessly grim and breathtakingly gorgeous, endlessly vast and claustrophobic, evoking a vibrant halo in the midst of hell. Allow yourself to be hypnotized by its sedate, melancholy allure, and you will be rewarded with a deeply affecting experience.

A Kashmiri nurse who lives in a village with her daughter and elderly mother-in-law, Aasiya (Shilpi Marwaha), seeks to obtain a death certificate for her missing husband. Declared a half-widow by the corrupt government, Aasiya has no choice but to visit the local registrar officer (Ajay Churney), over and over again, begging for the document that would allow her to move on with life. Her attempts are futile – until she’s faced with a choice that no human being should face. The final ten minutes of the film are so soul-shredding and darkly ironic – “How can a dead person murder someone?” – they make the sometimes-ponderous preceding seventy minutes well worth it.

“Aasiya seeks to obtain a death certificate for her missing husband…”

Morchhale utilizes a mostly non-professional cast playing themselves, which imbues the film with verisimilitude and authenticity. Shilpi Marwaha provides a deeply charismatic and introverted performance, pulling us deep into her world with nary a word. The real revelation here is Bilal Ahmad, a real-life cab driver, whose ceaseless optimism, wit and lyricism go a long way in counterbalancing all that desolation. He does not fear the wrath of man, only God. “Here, youth and fruit sour very quickly,” he comments cheekily about the terroir.

In a sparse narrative, every word matters, and Morchhale’s dialogue – despite the subtitles’ poor quality – shines. “Do poets earn enough to fill their stomachs?” Bilal asks his passenger. “You really make good jokes,” comes the reply. “Why [would] someone become a poet if his stomach [were] full?” At another point, Aasiya ponders: “I don’t know why I hope against hope.”

As the radio crackles reports of terrorist attacks, as impoverished folks struggle to survive the harsh bureaucratic regime and rough climate, as uniformed guards disappear the day after accepting fruit from a kind stranger, Nature looks on, majestic and unsympathetic. Morchhale would wholly embody that pitiless gaze, were it not for tender moments, such as the opening scene of Aasiya tying her mother-in-law to a chair by an open window so that the ailing woman wouldn’t fall forward. Those embers of affection are what sustain us, make us human. Widow of Silence demonstrates how they may also grow into an all-encompassing inferno.

"…Morchhale firmly establishes himself as the leader of the Indian New Wave"