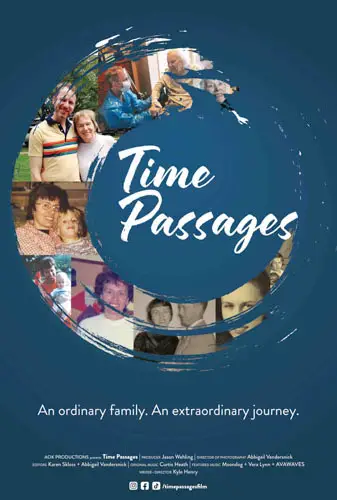

There’s a delicate honesty at the heart of Time Passages, Kyle Henry’s deeply personal documentary which straddles the line between memory and mourning, self-portrait and family archive. What begins as a document of his mother Elaine’s descent into dementia becomes a fluid exploration of identity and memory, and the strange business of recording, editing, and presenting your own family’s pain.

In less skilled hands, that might sound like an exercise in narcissism. But Henry, a filmmaker and academic with an editor’s eye and a confessor’s soul, isn’t interested in sanitising grief. Instead, he leans into its messiness. Time Passages is full of moments that feel intuitive, even unpolished, as though he’s working out the film’s structure in real time, and that’s entirely the point.

Framed through the lens of the Covid-19 pandemic, when Henry could only speak to his mother through screens and wires, the film takes on an added urgency. Locked away in a Texas care home, Elaine is already slipping beyond the reach of language. So Henry sings to her, plays her old tunes, clings to the fragments of familiarity that Alzheimer’s hasn’t yet claimed. And in parallel, he assembles a mosaic of her life from old home movies, letters, sketches, and sound recordings, preserving what disease has begun to erase.

“… a document of his mother Elaine’s descent into dementia…”

It is a film as much about reconstruction as remembrance. Henry’s decision to appear on screen, sometimes impersonating his mother in drag, might seem absurd on paper, but within the film’s handmade aesthetic, it works. It’s part therapy, part role-play, part filmmaking experiment, like Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture crossed with a late-night monologue. These scenes, though perhaps divisive, carry an emotional weight that’s difficult to dismiss.

There’s humour, too, which is wry, understated, and welcome. The film gently pokes at its own pretensions, questioning its purpose even as it unfolds. The scenes where Henry talks directly to camera, while wrestling with the ethics of representation, give the film a confessional texture. Then there’s Elaine herself: vivacious, flawed, opinionated. Her voice, whether captured in grainy footage or echoed through Henry’s performance, grounds the film in humanity.

What elevates Time Passages is its embrace of contradiction. It is meandering yet purposeful, poetic yet raw. Structurally, it’s loose, at times frustratingly so, a tangle of timelines and emotional strands, but that, too, feels honest. Memory is not a linear medium, nor is grief.

The film’s craftsmanship is quietly impressive. The editing by Karen Skloss and Abbigail Vandersnick threads the past and present into something organic. Visually, it avoids slickness, favouring a handmade quality that’s fitting for a story so intimate.

Time Passages is an acquired taste. It forgoes neatness in favour of emotional resonance. But for those willing to sit with its uncertainties, it’s a moving, quietly audacious film, less a biographical portrait than an emotional excavation. A son’s love letter to his mother, written in fragments, shadows, and song. It’s a personal memory box, left slightly ajar, and is all the more affecting for it.

"…a moving, quietly audacious film..."