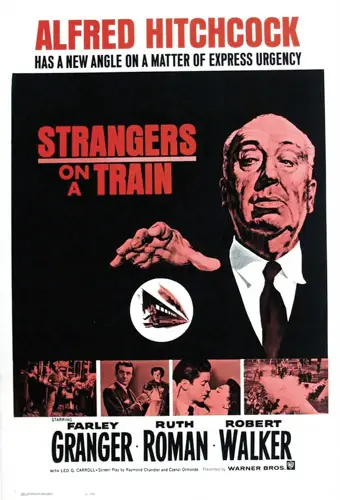

TCM CLASSIC FILM FESTIVAL 2021 REVIEW! How much should a traveler engage with an unfamiliar fellow passenger when both must share an intimate space in transit? As the plot spark of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 psychological thriller Strangers on a Train, this common social conundrum devolves rapidly from awkward politeness and curiosity to innuendo, and then to unwelcome, and deadly, personal intrusion.

An accidental, under-the-table toe-tap aboard a Washington, D.C.-to-New York train lands buttoned-down tennis-pro Guy Haines (Farley Granger) in the sights of nattily attired Bruno Antony (Robert Walker), a self-described “bum” and college dropout who lives vicariously through headlines, celebrity gossip, and his otherworldly fantasies. After an exchange of pleasantries, Bruno sidles up to the increasingly uncomfortable athlete and casually reveals that he knows all about Guy’s failing marriage and mistress, Anne Morton (Ruth Roman), thanks to the tattle columnists.

While looking his reluctant lunchmate up and down, Bruno, who has endured a life of belittlement by his rich, unforgiving father, hooks Guy with what at first seems a joking proposition: that these two complete strangers each kill the other’s problematic relations; in Guy’s case, his unfaithful wife, Miriam (Laura Elliott, AKA Kasey Rogers). “You do my murder, I do yours,” suggests Bruno, explaining that such a “crisscross” would eliminate motive. Guy exits, appalled, but inadvertently leaves Bruno enough information to embark on a one-sided, blackmail-minded homicidal mission.

“…these two complete strangers each kill the other’s problematic relations…”

Working from a screen adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 novel, Hitchcock sets the wheels of suspense in motion efficiently in an atmospheric and stylish first act. Save for a D.C. socialite party scene that abruptly turns shocking, the sinister one-on-one momentum established in the early going partly derails as the second act unloads a boxcar of supporting and peripheral characters, including several lackluster law enforcement types. Most annoying is Anne’s younger sister, Barbara Morton (Patricia Hitchcock, the director’s daughter), who, after supplying forced comic relief and unsolicited speculation about Guy’s Bruno dilemma, is redeemed somewhat by the story’s often strikingly visualized themes of doubles and human duality.

Robert Walker’s turn as the psychotic Bruno, deftly alternating between suave, fey, and evil, largely powers the film past its lapses into silliness and some uneven acting by a couple of players. Walker is an aggressive, clever cat to Granger’s cornered, uncertain mouse — an eruptive id stoking both men’s worst impulses. And while the homoerotic tension he creates through furtive looks, gestures, and dialogue may have escaped midcentury mainstream audiences, it’s now right there on Bruno’s seersucker sleeve. The actor’s compelling work is a forerunner to obsessive, stalking screen villains etched by the likes of Malcolm McDowell, Kevin Spacey, and Glenn Close decades later.

Strangers on a Train, of course, showcases the technical prowess and brilliant editing that are among the hallmarks of Hitchcock’s work. As in other famous thrillers from the filmmaker, the growing danger is interlaced with ironic twists (including, in this case, a perverse reversal on the fateful footsie that connects the two men). The movie’s metaphorical, choose-your-own-interpretive-adventure climax in an amusement park is a dizzying ripsnorter, at once scary, funny, and, even within this scenario’s surreal confines, wholly implausible. It’s also unforgettable.

Strangers on a Train screened as part of the 2021 TCM Classic Film Festival.

"…growing danger is interlaced with ironic twists..."