NOW IN THEATERS! For anyone who has ever studied film or appreciates the cellular art form, there is a fascination with filmmakers who break barriers or “crack the eye.” Contributing to a visionary pursuit, Leni Riefenstahl created her most significant works, Triumph of the Will and Olympia, while working under commission from Adolf Hitler as a Nazi propaganda filmmaker. She praised fascism through body worship and celebrated superiority. However, Riefenstahl denied her allegiance to the Nazi regime and repeatedly said she had no idea about the Holocaust, dying at the age of 101. Her support for Hitler was consistent with most of Germany as he rose to power.

In the compelling and somewhat disturbing documentary, Riefenstahl, filmmaker Andres Veiel explores Leni Riefenstahl’s extensive archives and examines her filmmaking to reveal truths and uncover her efforts to “rewrite history.” With access to Riefenstahl’s estate, including private films, photos, recordings, and letters, Veiel provides insight into the historical context in which the celebrated Nazi filmmaker operated, highlighting her close contact with Hitler and her husband, who was committed to the Nazi regime as an officer. In the aftermath of the Nazi regime’s fall, Riefenstahl spent the rest of her life claiming innocence, which hardly makes sense. Nevertheless, despite her controversial past, Riefenstahl’s work is studied and remains a pinnacle of cinema, especially today when a resurgence of fascism has become more evident.

A vain and driven woman with few female friends and several male partners who all supported her, Veiel establishes his subject’s close association with Adolf Hitler as an important detail in her filmmaking. Where do you draw the line between art and vision while providing support for one of mankind’s most outrageous atrocities, with an evil that is difficult to suppress even in the 21st century? Claiming political inexperience, only her ability to set up 30 cameras and multiple camera elevators and pans, including placing cameras in balloons, was ingenious for its time. Her syncing and editing were mesmerizing, revealing her empowerment for film and craft. Yet, her coverage may have revealed more than what was going on. It’s feverish, and scary, dark, and shadowing.

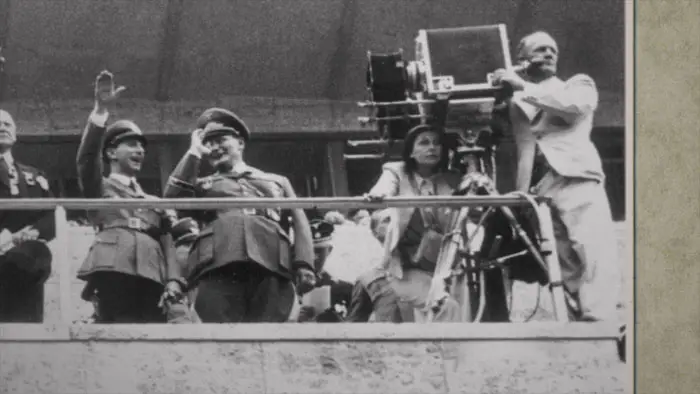

Leni Riefenstahl behind the camera during the filming of Olympia alongside Nazi officials in 1936.

(c) Vincent Productions

“In the aftermath of the Nazi regime’s fall, Leni spent the rest of her life claiming innocence, which hardly makes sense…”

Veiel not only provides details of letters and images throughout Riefenstahl but also constructs a story of filmmaking through his own film. He conveys the emotion of “how could she” using selective footage and placement, timed interviews, behind-the-scenes actions, and subtle narration, allowing imagery to tell a story for the viewer to decide their side.

Veiel also begs the question of what is the artist’s responsibility. Riefenstahl had supporters and fans who carried her opinions. Her partners, including Horst Kettner, 40 years younger, supported her. She held hands with the Führer, and there is Joseph Goebbels, the worst Nazi of them all, whom she claimed he assaulted her. She was not afraid of work or extreme conditions, especially working with Arnold Fanck, which perhaps gave her the armor to live her life in denial. Even when she worked in Sudan, it was still unconvincing that she was not a Nazi sympathizer.

With all the impressive archive footage and meticulous arrangement and presentation, Veiel presents Leni Riefenstahl’s life and persona as beautiful and most unsettling. Perhaps the guttural sound of German adds another layer of revulsion, but Veiel does give Riefenstahl due as a talented pioneer in film, which might be hard to swallow, just as it undoubtedly became for her.

Header image copyright of CBC.

"…beautiful and most unsettling."