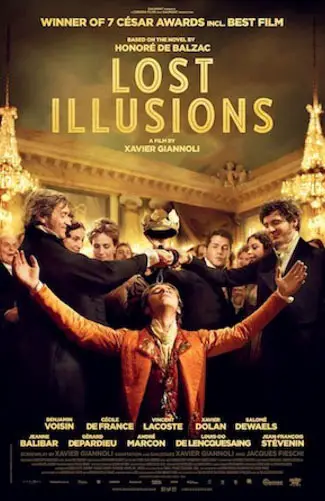

Xavier Giannoli’s cinematic adaptation of Honoré de Balzac’s Illusions perdues, Lost Illusions, happens to be the first to grace silver screens. The three-part novel has only been adapted three times prior: a made-for-TV film, a stage play, and a ballet. It’s no simple task to condense such a gargantuan piece of literature into a feature-length film, but the director is up to the challenge. There’s nary a hint of faltering in the epic narrative – the script was co-written by Giannoli and Jacques Fieschi – which trots along leisurely but confidently, like a 19th Century stallion on cobblestone Parisian streets.

From the sweeping, opening orchestral motifs, it’s apparent that this is a grand, old-fashioned retelling of a classic tale. An orphan working at a small-town printing shop, Lucian (Benjamin Voisin) harbors monumental ambitions of becoming a great writer. When an older, married aristocrat Louise (Cécile de France), with whom Lucian is in love, sees potential in him, Lucian accompanies her to Paris. Despite feeling overwhelmed, the young man refuses to become just another “provincial flocking to the capital.” Not fitting in and being told to return to his village just fuels his mission.

“…Lucien soon meets Etienne Lousteau, who…reveals the truth behind the industry…”

Although finding newspapers crude at first, Lucien soon meets Etienne Lousteau (Vincent Lacoste), who brings him on as a copywriter and reveals the truth behind the industry that supposedly promotes literature and art. Critics are shamelessly bought; it’s all about “raking it in.” Both appalled and seduced, our hero climbs the social ladder, falling for married actress Coralie (Salomé Dewaels) along the way. Before he knows it, Lucien embraces the bureaucracy, even ensuring Coralie gets cast in a highly competitive role. I won’t spoil the ending for those unfamiliar with the source novel.

Giannoli doesn’t aim to embellish Balzac’s hapless life with modern stylistic flourishes, a-la Baz Luhrmann. Instead, he focuses on how little our values have changed since then, depicting issues that remain as pertinent as they were hundreds of years ago: corruption on a massive scale, brazen advertising, biased media, radical class divisions, and blind pursuit of “raking it in”. These days, Giannoli seems to say, just like in the mid-1800s, to become a famous writer, you kind of already have to be famous.

"…trots along leisurely but confidently, like a 19th Century French stallion on cobblestone Parisian streets."

[…] Supply hyperlink […]