Six months after Jordan’s tragic death, his mother Virginia passed. That took its toll on Ernest and his children. A lengthy process ensued, with multiple figures within a variety of community and government echelons fighting for “the plight of aboriginal children across the country.” In 2017, the Jordan Principle was finally recognized as a law. The film ends with a touching sequence at the Jordan’s Principle Summit, wherein the Andersons were honored – in typically Canadian fashion – with a quilt depicting the country’s national flag.

“…fighting for ‘the plight of aboriginal children across the country.'”

If you have a heart, there’s no way you won’t be affected by the subject matter. Obomsawin lets the families of differently-abled children tell their stories, both harrowing and uplifting. They persevered against all odds, fighting for social justice, taking a stand against the directorate – “The conservative government fought to protect its own image,” Alanis narrates – and prevailing at the end. These are universal issues, bound to resonate.

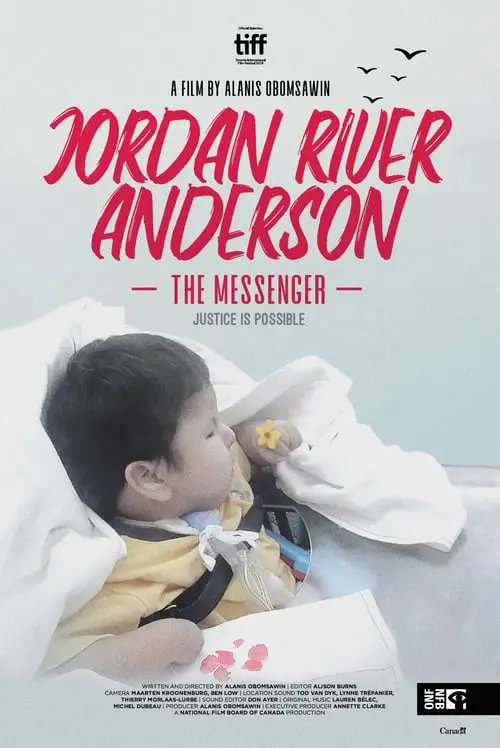

That said, while the documentary avoids being sensationalistic, it’s also rather unsensational. Its schematic structure is not helped by Obomsawin’s solemn, borderline-somnambulant narration. Extended sequences take place in hearing rooms; if footage of parliament members debating gets you riled up, then delve right in. Jordan River Anderson: The Messenger functions fine as a heartfelt, important PSA, a tribute to Jordan’s legacy – but less so as a fleshed-out, layered documentary.

Jordan River Anderson: The Messenger screened at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival.

"…if you have a heart, there’s no way you won’t be affected by the subject matter."

Would love to see this at the University of Manitoba in any relatable faculty’s course – law, social work, medicine, Indigenous studies.