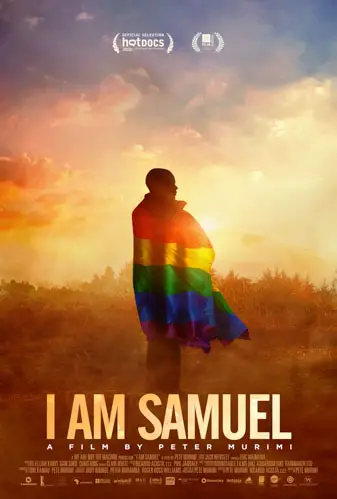

Peter Murimi’s I Am Samuel continues the recent trend of successful documentaries that examine the trials and tribulations that LGBTQ+ communities undergo throughout the world. Whether we’re privy to the institutionalized brutality against gay people in Eastern Europe in Welcome to Chechnya, or the general criminalization of homosexuality in Nigeria on display in The Legend of the Underground, it’s clear that vast swaths of the globe are sadly still hostile to the human rights of LGBTQ+ citizens. But, this begs the question, has the field become too crowded for a documentary like this?

No, because the film, written by Murimi and Ricardo Acosta, so intently focuses on the titular Samuel and his lover, Alex, that it is quite intimate. These young Kenyan men struggle with reconciling their relationship with Samuel’s conservative family and the draconian restrictions on gay rights in Kenya. It’s simply tragic that so many individuals are still forced to cut ties with their families just because of their expression of love, and the documentary does an admirable job depicting how two lovers try to manage both worlds.

I Am Samuel is filled with powerful images of domestic life in Kenya contrasted with the country’s unique topography. At a brisk seventy minutes, the film covers a lot of ground. We spend large portions of the film in the busy capital of Nairobi, but the most affecting sequences take place at Samuel’s small family farm in rural Kenya. Here we are introduced to his family, with the most attention being given to his religiously devout father, who is in a state of constant denial about his son’s sexuality. While the relationship between Samuel and Alex is compelling in and of itself, this father-son dynamic provides the most potent emotional throughline.

“…struggle with reconciling their relationship with Samuel’s conservative family and the draconian restrictions on gay rights in Kenya.”

The director shows restraint by not delving into the politics as he easily could have devoted extensive segments to the Kenyan penal code or the high rates of HIV transmission in East Africa. Instead, Murimi wisely recognized that the standard documentary composed almost exclusively of talking heads would not have been as effective. But because we are left without a true resolution, we’re missing the anticipated poignancy of the conclusion. Even so, we’re so accustomed to documentaries containing grand gestures designed to inspire social change that it’s refreshing when a filmmaker brings down the scale to a personal level.

Of course, one naturally gravitates towards the latter when one is aware that I Am Samuel is banned in Kenya. That a relatively innocuous and modest story of two gay men has been deemed by the authorities too threatening to their countrymen is as strong of a sign as any that change is desperately needed in Kenya. We cannot do much as filmgoers to affect change other than spreading the word on documentaries like this. But, the power in stories that humanize “others” is key to progressively eroding the ignorance that is endemic throughout the world. One film won’t necessarily change society but sharing these stories as a form of collective action is a step in the right direction.

"…key to progressively eroding the ignorance that is endemic throughout the world."