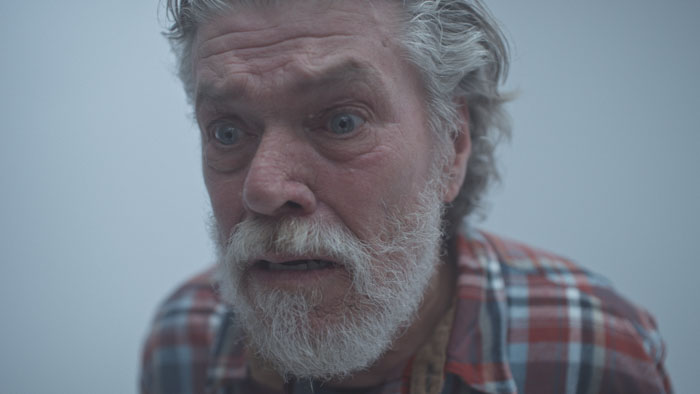

Ward’s restrained yet emotionally layered portrayal is punctuated by interior voice-over monologues. This device was used in Thornton Wilder’s stage classic Our Town, having a remarkably similar theme of appreciating the present, the universality of human experience, and the inevitability of change, death, and time. It was an abysmal film in 1940, with William Holden staring at his feet as the voice-overs were delivered. It is somewhat better handled here, yet the effect is still the same, numbing sometimes numbly with a device better suited to the noir genre. Montgomery adds an unsettling anchor to proceedings. She seems to see through the masks of people, exposing them, taking the place of the interior monologues.

Herman falls apart as the story shifts more decisively toward overt supernatural confrontation. This causes the film to lose some of its earlier subtlety. Herman’s behaviour becomes more exaggerated, and the symbolic darkness he has been wrestling with turns increasingly literal. What had functioned powerfully as a metaphor begins to feel overstated, and certain moments verge on awkward rather than terrifying, giving the film a look of an intervention with CGI, giving it that neat solution to an often clichéd film situation. The film cannot escape the fact that this is a static stage story. The actors do their best shifting moods, but it ultimately comes down to revelations made in a student drama, making them trite. The revelations lack colour, reason, excitement, and horror of discovery. Even so, the film’s shortcomings do not negate its strengths of keeping the narrative going and having some interesting quirks to the characters that enter the cabin. The theme was handled strongly in Michael Vlamis’s Crossword, with the cabin being replaced by a well-appointed Los Angeles home in the hills.

“…its most compelling scenes are not its supernatural set pieces, but its quiet conversations…”

In the theatre, when a character enters, the mood should change with others in the room, and it does happen as each is given a chance to be who they are. But cinema is not theatre, and preachy dialogue demands to change and accept, leaving one cold simply because you don’t care about Herman as a character. He is an unfortunate fellow who had something happen to him, and he has chosen to hide away and consider suicide. Hollow, yes, even with some confusing flashbacks and supernatural declarations of love from spirits looking like Ophelia in Hamlet, minus the river.

Herman succeeds mostly as an advert for suicide prevention and intervention in people who may watch it and be triggered. Its most compelling scenes are not its supernatural set pieces, but its quiet conversations, particularly those in which Herman is forced, against his will, to articulate what he has lost and why. The film is thoughtful in moments, and it means well; perhaps for some, it will shine a light on their grief.

"…for some, it will shine a light on their grief."