As technology becomes more invasive and culture becomes more conformist—two trends more related than not—it’s understandable that Orwell and Huxley’s dystopian visions are often food for inspiration. Greatland nibbles, taking place in a future that assumes our weaknesses will exacerbate until they become our oppressors. While the country of Greatland partakes in some of the customary dystopian practices, such as an all-seeing familial figure (“Mother”) and outlawed procreation, the particulars of its future are more tailored to our present.

Our hero is named—wait for it—Ulysses (Arman Darbo). Should there be any doubt, a character is never randomly named Ulysses. The hero with the heroic name that connotes an impending journey wakes up in his big, pink, enclosed bed. From this womb, he crawls through a pink tunnel until reaching his bedroom, decorated in a less than traditional way for a fifteen-year-old boy. It’s filled with rainbows, unicorns, plastic mugs with smiley faces on them, and not a single Ramones poster.

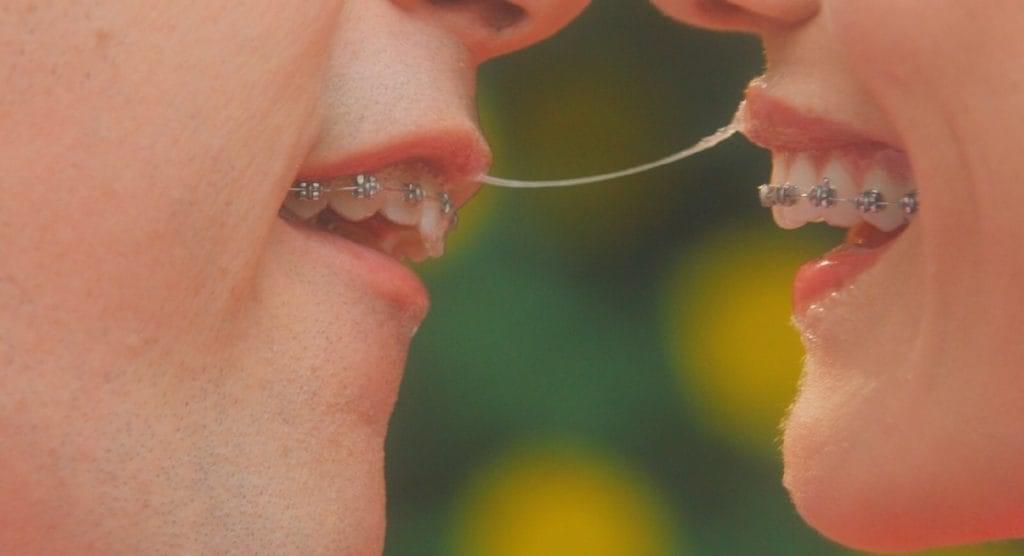

When Ulysses leaves his room, he’s dressed head-to-toe in pink, nails painted, and wearing a hairpin. It ceases to become a “hey, man, live and let live” situation when you see that the entire country of Greatland has the same aesthetic. The streets are filled with confetti, streamers, chalk drawings, and other multicolored lawn trash. Whatever hellhole the Teletubbies crawled out of upside-down, like Linda Blair, it probably looked like this.

“There is no death, no making babies, and no books—everyone is to be kept in the naïve, comfortable bubble of childhood…”

As you meet some of the world’s eclectic citizens, you find out that not only is it visually vomitous to anyone over the age of four, but the culture champions positive reinforcement above all else. There is no death, no making babies, and no books—everyone is to be kept in the naïve, comfortable bubble of childhood, hence the swap of Big Brother for Mother. One thing leads to another, and, well, his name is Ulysses.

Written and directed by Dana Ziyasheva, Greatland does its best work in the beginning, establishing the world and rattling off a bunch of cultural in-jokes. For instance, when a citizen of Greatland defies the orthodoxy, he or she is made invisible and mute. There’s a word for that, I think. Since sex is a no-no, all marriages are arranged, which might not be so bad if plants and animals weren’t given the same rights as humans. Ulysses’ poor friend is married to a birch tree. All of this is solid satire of a certain social movement—lump it into Harold Bloom’s “school of resentment”—but things get shakier when the journey begins.

As the cast grows and the setting extends beyond Greatland, the movie pushes its ideas and jokes to the wayside for intrigue, drama, and excitement. Due to some awkward acting and story meandering, it never convinces you of its stakes. That jarring tonal change makes the last third of Greatland a less fun, less inventive Logan’s Run. I will say there is some “weird for weird’s sake” future tech reminiscent of ’70s sci-fi, such as a quiz buzzer that must be held in your mouth like a snorkel. There’s also a reoccurring news program that looks like it’s broadcasting from Ziggy Stardust’s home planet.

"…takes place in a similar vision of the future one that assumes our weaknesses will exacerbate until they become our oppressors."