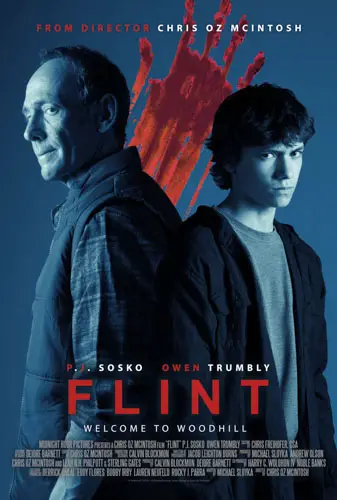

Thunder is clapping, and you will be too when you experience the near-perfect nail-biter short Flint, directed by Chris Oz McIntosh. It’s all coming down tonight at the Wood Hill Home for unruly boys, as young Scotty (Owen Trumbly) has a knife and has run out the door into the woods. The head of the program, Eric (P.J. Sosko), insists on going after Scotty alone, leaving the other counselors to look for Terrence (Dash Mellrose), another boy who went missing earlier.

We then jump flash to daylight over a month ago, to when Scotty’s parents, Casey (Todd Jenkins) and Lisa (Becky Bartlett), dropped him off at Wood Hill per court orders. Scotty had beaten a classmate bloody and then punched the cop who tried to intervene. Eric tells Scotty about the indigenous creation legend of the twin brothers, Sapling and Flint. Sapling was all things growing in the spring and summer, while Flint was all things destructive throughout fall and winter. Eric says it is his job to try to get the Flint out of Scotty.

We then flash forward back to the woods, where Eric finds Scotty making slices into his own arm…

We can talk for days about how well Jacob Leighton Burns shot this, with highly stylized lighting applied to naturalistic settings in a precise way to darken the atmosphere. We could also have long discussions about how masterful Sosko’s performance is here, as he is a paragon of true villainy. Trumbly also impresses mightily, expertly riding a range that goes from repressed to rage. We would conclude that director McIntosh wrangles all these elements into the thirty-minute cinema symphony that is Flint.

“…Scotty had beaten a classmate bloody and then punched the cop who tried to intervene.”

All of that is well and good, but it doesn’t even scratch the surface of the greatness here. Paramount above all else is McIntosh’s magic with the razor, as his skill set as an editor is unmatched, even among record holders like Jonas Åkerlund. The opening scene’s alchemy of cuts instantly draws the viewer’s attention, with its alternating simmering exterior shots of the group home, intercut with laser-fast sequences of all Hell breaking loose and rolling for the door.

Aspiring filmmakers should study this opening sequence, as it shows the kind of dynamic start needed for a strong film. Once watched, hopefully, no film will ever start with someone waking up in the morning again. There is also an amazing section where several scenes of brutality are lined up to match the shot, showing the passage of time through the beat of repeated abuse. I was hoping for another feat of editing flourish in the finale for a trifecta, but the path taken didn’t call for one.

I respect the direction that McIntosh took instead of a cathartic release, as we are still dealing with youth behavior centers torturing children. If you don’t live with the daily consequences of having survived or living with someone who survived these abuse camps, Flint will give you a touch of the heat of the inferno this topic sparks. As close to cinema perfection as we dare get.

"…As close to cinema perfection as we dare get."