In the film, many people in Belarus and Poland don’t realize that Syrian refugees like Bashir (real-life Syrian exile Jamal Altawil) and his family are trying to escape from ISIS, not perpetuate their tyranny.

Exactly. Some of them are running from ISIS. Some of them are running from hunger and from domestic wars and from the extreme heat. It’s many reasons why the people of the south are leaving the failing states, and mostly I think we in the West are responsible for that situation. They have hundreds of reasons to run and to try to reach the paradise, the rich, democratic countries where they believe they will be safe.

In the beginning and what happens later in the film could not be a greater contrast because as their plane is starting to land in Belarus, they think that it’s only going to be a few days before they’re in Malmo, Sweden with Bashir’s relatives. They don’t realize that they are going to be in for a long-term struggle.

It also strikes me that I was documenting a new corridor of migration that was opened artificially by (Belarusian President) Alexander Lukashenko and Putin to destabilize the countries of the European Union. Because after the first refugee crisis in 2015, during the Syrian Civil war, it became obvious that Europe was not at all mentally prepared to accept the bigger number of people of different religions and colors.

And so the dictators like Putin immediately found a very efficient and cheap weapon to target the Union. And unfortunately, the politicians in the Union responded exactly the way (Putin and Lukashenko) planned. It means with fear, violence and manipulation. Normally, when they decided to go to Europe, they paid for a little boat that would take them over the Mediterranean. Sixty thousand people had already perished.

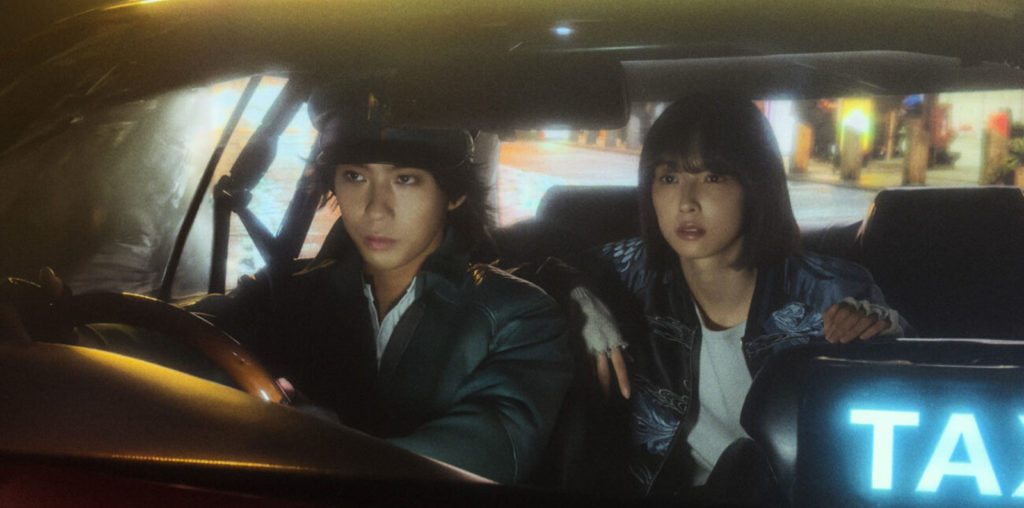

They knew where they were going, but at that corridor, it was very civilized. They had to buy a visa then take a plane, where they’ve been treated like the normal citizens of of the world.

And after that, they stay in a hotel in Minsk or to take a taxi to the border, and suddenly, when passing the borders, this situation totally changes. They believed that they are going to paradise, but they have found themselves in Hell. It is a very strikingly nightmarish situation. And I was thinking a lot about Dante’s Inferno as a figuration of that kind of situation.

“They believed that they are going to paradise, but they have found themselves in Hell.”

Shooting the movie in black-and-white was very effective because it put viewers in the characters’ place. You can’t tell if you are on the Polish or Belarusian side of the border.

You are in that huge, vast forest, and suddenly you have people who are your enemies and who don’t see the human being in you. You are chased like an animal, but are actually threatened with war. They’re not under the protection for sure. I’m speaking about the migrants.

Green Border reminds me of Jean Renoir’s The Grand Illusion because it changes languages so often. It adds to the tension because the dialogue changes from Arabic, French, and English to Polish, and many of the characters have no idea what each other is saying. Normally in dramas like these people speak a single language or have accents.

I wanted to show that alienation and the differences and the unity at the same time. Because by the end of the day, you know, when you find yourself in a situation like that, when you can die or you can be saved, when you suffer, when you are cold, hungry, afraid, we are all similar. We are all the same. Somehow, we are naked.

It doesn’t matter what language we are talking. If you find the human being, you can always find the language you’ll communicate with.

Your movie is not joyless. I adored the beatbox scene where you have the people from Congo and Poles beatboxing together. How did you guys come up with that sequence?

It happened in reality. A situation like that happened in the house of my friends who were living in the area and who decided to hide for some days three or four teenagers from Africa. They and their own children took care of them. And they had a common language because the children were in a quite rich household.

The children went to the French school, so they spoke French and then, and the teenagers had been from French speaking Africa. Suddenly they found such a common interest. After one hour the ice had been broken and they’ve been like, you know, part of normal teenagers no matter where.

That’s cool.

It was the most optimistic event which happened because you’ve seen the potential for unity and communication. It’s not like we don’t have the resources, we just don’t want to use them.