Michael Day’s Clawfoot is one f***ed-up flick. It maintains an ice-cold satirical tone while upping the ante on casual viciousness, morphing from a psychological cat-and-mouse game into a sadistic bloodbath. It draws a few controversial conclusions in its dissection of classism and toxic masculinity. It pits Clint Eastwood’s daughter, Francesca, against Mel Gibson’s son, Milo. All these elements may not entirely cohere, but this chamber piece is unlike anything I’ve seen in a decade, twisting expected conventions on their head.

When contractor Leo (Gibson) shows up at Janet’s (Eastwood) house to fix her bathroom, she’s reluctant to let him into her multi-million-dollar mansion. There’s something off about him. Yet he presents her with papers stating that Janet’s husband, Evan (Nestor Carbonell) – who’s gone missing – hired him, and she lets him in. Leo is borderline obnoxious in how casually he oversteps boundaries. He goes through her fridge, rummages through her belongings, invites a coworker, Samuel (Oliver Cooper), lets himself in the next morning, makes breakfast, and starts pounding through her walls.

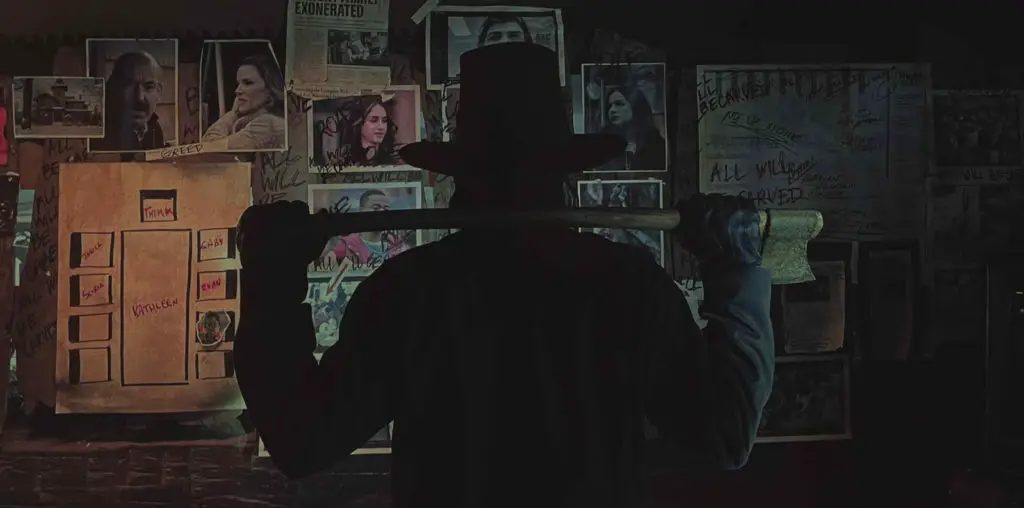

As overbearing as he is, Janet’s no peach either. Judgmental, referring to Leo as a “working man”, she epitomizes every stereotype that’s attributed to wealthy housewives: obsessed with looks, money, and living in the clouds. She also harbors murderous fantasies, in which she violently bludgeons Leo with a variety of items. She shares those fantasies with her lawyer BFF, Tasha (Olivia Culpo), who totally gets it. As the plot unravels, the two form an unholy, pseudo-revenge-feminist team of sorts.

“…he presents her with papers stating that her husband hired him…”

By taking things to an extreme, director Day and writer April Wolfe seems to ask: when does a lot become too much in these days of ideological madness? Sure, their film functions as a pretty brutal condemnation of predatory men, particularly – surprise! – straight white males, but it also, gasp, has the gall to wonder whether radical feminism is the answer. The sly interweaving of a socioeconomic imbalance only magnifies these issues, Leo being from a low-middle-class background and Janet having escaped it and become accustomed to a frivolous lifestyle. He’s acting out of need. She’s acting out of privilege and dark fantasies.

Clawfoot is surefooted when it comes to the brisk pace, the tongue-in-cheek tone, the quirky score, and the snappy dialogue from the capable leads (“Not the cabernet, you f*****g peasant!” Janet screams at one point). There’s even a funny little homage to film noir mixed into this delirious concoction. But the film is not without its flaws. The first half of the narrative is sharper than the second, when most of the tension and humor are dependent on the interplay between Gibson and Eastwood. When things slide into grisly territory, the filmmakers fare worse, losing some of the delicious ambiguity prevalent in Act One. The film also comes dangerously close to crossing the line from “inspired and weird” to “ridiculous”, but thankfully never does.

For a low-budget, contained flick, Day’s film does a remarkable job of keeping audiences riveted with a minimum of pyrotechnics. It doesn’t aspire to greatness, knowing perfectly well what it is: a lean, mean, bloody little machine with a few subliminal – and not-so-subliminal – messages thrown in. Dive right into this tub.

"…unlike anything similar I’ve seen in a decade, twisting expected conventions on their head..."