In today’s society, it seems that mankind is withdrawing further and further away from the importance of the natural, while orcishly hurtling towards a false sense of gravitas, sought after in the un-organic, technological distractions. This atheistic and objective view of the world hasn’t changed since the great inception and implementation of the movement of modernism over 100 years ago. Of which German Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche “christened” in the late 1800s with the conclusive phrase—”God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” This chaos-ensuing cynicism did not “resonate” per se with C.S. Lewis’s cynicism. His take on it was, “No, I did not believe God existed. But I was angry at God for not existing.”

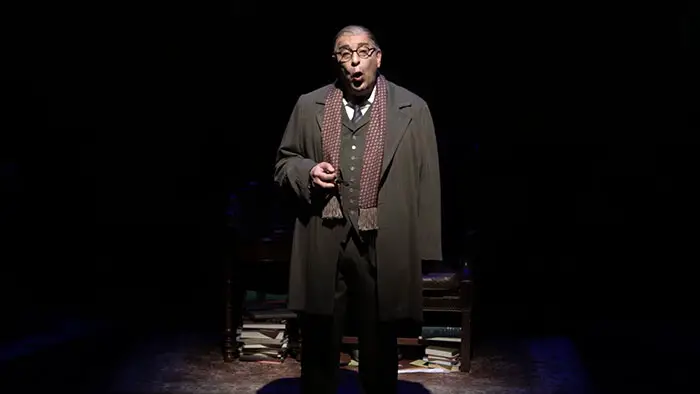

Max McLean’s C.S. Lewis Onstage: The Most Reluctant Convert explores the embodiment and incarnation of one of the most prominent atheist-turned-believer authors of the twentieth century. It is important to note, however, that this is not a piece employed to convert anyone who voluntarily (or under duress) is seated in the theatre to watch the play. No. McLean portrays Lewis with precise symmetry in order to transform into the Oxford University lecturer to perform a piece. Instead of finding yourself listening to the Charlie Brown Teacher’s “Wah wah wah wah wah,” you will be illuminated by the sincere, warm, and scintillating conversation of the supreme, yet charming, intelligence and comprehension of a man whose brain is the size of a planet, and yet his outlook on life humbly celebrates nature, history, and the arts.

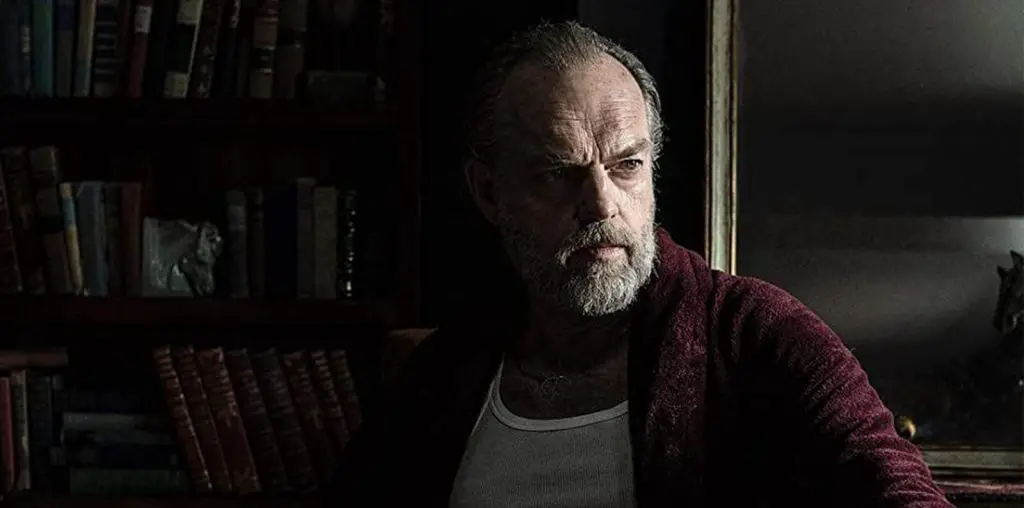

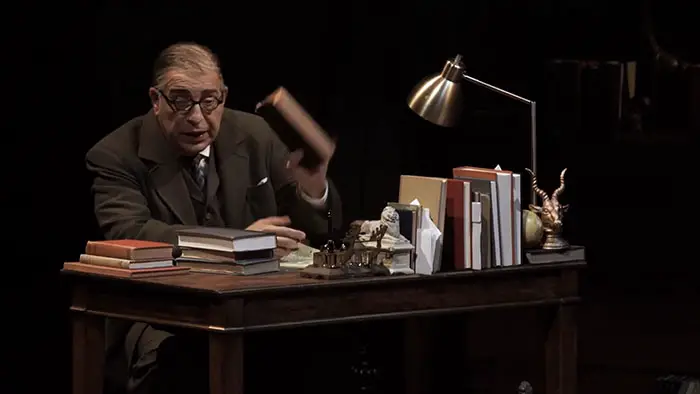

The most existentially crucial events of C.S. Lewis Onstage: The Most Reluctant Convert are mental. Their perceptive impetus concerns how thought A prepares for thought B, which propels realization C, amounting to surreal instants on stage and in one’s own mind. With 70 minutes of run time, no intermission, and 11 Acts, McLean gently holds his enthralled audience in the palm of his hands throughout his Shakespeare-esque performance—delivering Lewis’ eloquent writings and embellishing them with elegant sentences. McLean obviously, yet deferentially, relishes his work, savouring every phrase and pause with decorum and grandeur. If one is not acquainted with Lewis beforehand, then they definitely will be after the play is long over. McLean’s portrayal will resonate with audiences throughout the years. If one is to go further and listen to tapes of the real C.S. Lewis’ voice and compare them with McLean, telling the two apart is nigh on impossible. With the set mirroring the organized clutter of Lewis’s Oxford office, ancient books, pipe smoke, and a frequented leather chair, McLean upholds Lewis’s war-time propriety with a tweed jacket and trousers, grounded with a pair of polished brown brogues and gentleman’s side parting. It is as if Lewis himself is standing welcomingly at centre stage.

“…the embodiment and incarnation of one of the most prominent atheist-turned-believer authors of the twentieth century.”

Opening the play with stories of Lewis’s childhood, McLean details the death of Lewis’s beloved mother Florence, and his relationship with his brash and onerous father, Albert. His father was gifted with an unrelenting and volatile talent for verbal assault and disproportionately reacting to the actions of his two little boys. His demenor provided an unbidden source of misery for Lewis and his older brother Warren.

As Lewis attempted to meet this opposition, the audience is shown an emergence of a young man’s sophisticated intellect and coherence. From time spent with a private mentor, this further nurtured and cultivated Lewis’s articulate command of literature and the English language—invigorating his desire to pursue deeper meaning. Nevertheless, Lewis religiously faked the acceptance and involvement of his religious upbringing by his father out of an instilled fear for greater disapproval.

Lewis’s disbelief transformed into materialism—a form of atheism, with the “understanding” that there was no cosmological order orchestrated by an almighty and omnipotent being and certainly no primary mover. Everything that was or had been having occurred due to the movements of mere atoms careering arbitrarily through space…quite unexpectedly, later presenting itself to Lewis was a mental plot twist beyond meagre surmising . Lewis realized that the mind could not explain itself. Consciousness, sentience, rationality, and perception are impossibly ordered as intricate bodily implements to experience the universe a result of pure pandemonium and complete accident due to the random composition of bouncing atoms. “It must be more than biochemistry.” Deliberate and purposeful arrangement of the complex must be the answer. The answer in question is God—to which Lewis reluctantly and objectively concludes the play with, “I believe.”

Had Lewis not attained and embraced this revelation, with help from Tolkien’s influence and teachings, one being that “the Gospel story is a myth working on us like other myths, with one difference: it really happened,” then perhaps without this pivotal acknowledgment and embracing of God, Lewis would not have lived the life he lived, and The Chronicles of Narnia would have never been written.

"…portrays Lewis with precise symmetry..."