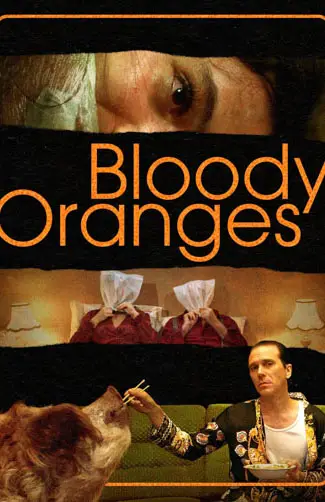

Director Jean-Christophe Meurisse’s Bloody Oranges starts with a panel of judges arguing over selecting finalists for a rock dance contest. The judges, all with different ideas and perceptions, struggle to reach a unanimous decision. However, they work it out when the sponsors ask them to choose “people-pleasing” winners, hinting that the contest isn’t the fairest. But that’s just the setup leading to a highly unpredictable story and a transition from a comedy into a very gritty and macabre outtake on France’s social complications and their consequences.

The comedic crime drama intertwines four separate story arcs. First, an elderly couple, Olivier (Olivier Saladin) and Laurence (Lorella Cravotta), is trying to win a dance contest, the same one that is semi-rigged. Their career-obsessed son, Alexandre (Alexandre Steiger), is a hot-shot lawyer for a well-connected firm who is on his arrogant journey to endless success. Then there’s Finance Secretary Stéphane Lemarchand (Christophe Paou), who’s on the verge of being exposed for tax evasion and fraud. All the while, innocent Louise (Lilith Grasmug) is trying to woo her crush and lose her virginity to him.

“…an elderly couple…is trying to win a dance contest…that is semi-rigged.”

Despite a few characters already interacting in the first half, their stories are not concerned with one other. During this section, the themes remain well-hidden, wherein co-writers Meurisse, Yohann Gloaguen, and Amélie Philippe intentionally try to veer the audience into a different zone. A quote from Antonio Gramsci, “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters,” while not giving away much, it denotes a stark transition. It points to the tension that’ll overtake the stories that the film has established. And it does get intense.

This is when Bloody Oranges undergoes an epiphanic transition in terms of both its narrative and thematic interpretations, giving us an allegorical depiction of modern-day France’s social issues. Here, the stories intertwine, and each characters’ impact on the other is visible. Moreover, the complex connection of dots between all events centered around our protagonists reveals the underlying subtexts of crime, capitalism, societal grading and stratification, and the consequences of corporate profiteering.

The first sequence, where judges select winners based on popularity and not talent, is a direct setup against the unfairness people face due to these complex socio-political scenarios that put profit before them. The writers cleverly create this melange of stories that comprise characters of different backgrounds and personalities. The film creates an atmosphere where the relevance of the conspicuous relationship between each narrative strand is profoundly encapsulated in visuals, not dialogue, leaving most of it to viewers’ interpretation.

"…somehow registers itself as an important film and proves significant in every cinematic sense."