It’s challenging to pinpoint filmmaker Boaz Yakin’s style. As a writer and director, he’s responsible for films as varied as the original Punisher adaptation, the gritty urban drama Fresh, the soapy sports flick Remember the Titans, the fluffy rom-com Uptown Girls, and the sleight-of-hand thriller Now You See Me. The less said about Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, the better. Yakin is consistent at being inconsistent. He continues that trend with the out-of-nowhere, poetic, experimental, indie drama Aviva. It couldn’t be any more different from the filmmaker’s previous output and is all the better for it. Unchained from the artifice of the Hollywood system, Yakin seems to finally, truly express himself here.

The filmmaker makes his intentions clear from the start. His nude characters break the fourth wall as they address the audience directly with smug monologues about said filmmaking artifice and sexual role reversals. “I’m acting right now,” states Bobbie Jene Smith, a choreographer who plays the female version of a male character called Eden (Tyler Phillips). “I didn’t write these words. They are written by what we, as a species, currently refer to as a man.” On the flipside, Eden’s partner, Aviva (Zina Zinchenko), is played by Smith’s fellow choreographer, Or Schraiber. The four are interchangeable throughout the narrative.

“…different iterations of Aviva and Eden argue, make love, search for a new apartment…”

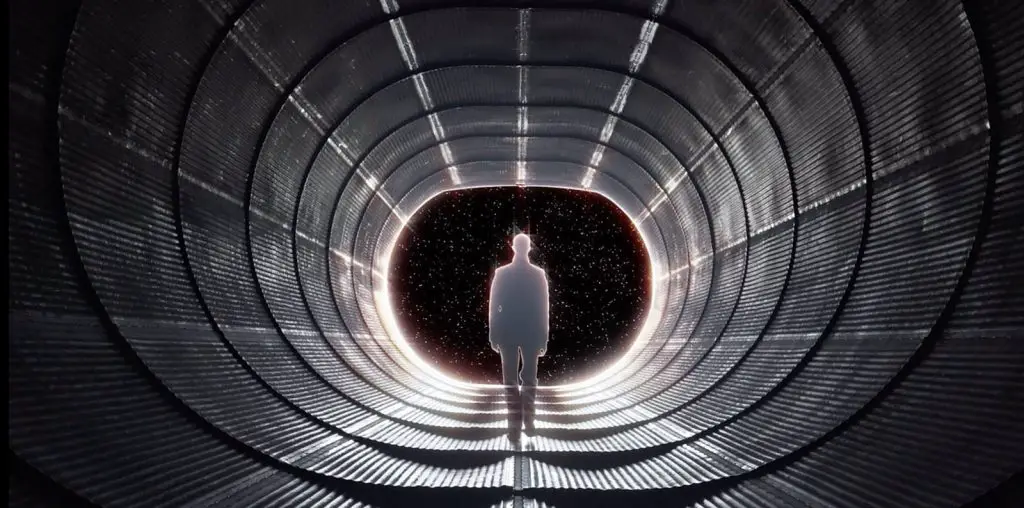

Confused yet? Aviva is meant to be disorienting, but pleasantly so, a kaleidoscopic whirlwind of sounds and images. Through this colorful prism, Yakin observes the blossoming(s) and downfall(s) of Romance. The different iterations of Aviva and Eden argue, make love, search for a new apartment – the childish Eden literally manifested as a bratty child – go through immigration and marital woes (“I don’t even know who I am anymore in this fu**ing country!” Aviva shouts about our great nation), break-ups and reunions, and of course, dance, dance, dance.

It may all be a tad indulgent and overlong. Not all of it gels as well as Yakin intended: Aviva flips back and forward between narratives, non-sequiturs, tones, not to mention genders and timelines, with such reckless abandon, the orchestrator of this organized chaos can only be applauded for his audacity – and the fact that most of it actually does work. Yakin’s exploration of flesh, sexual desire, connection, and isolation is deeply sensual, built on juxtapositions, unabashedly romantic, and tongue-in-cheek (the purportedly French Aviva nonchalantly acknowledges her clearly-Russian accent).

"…Aviva is a palindrome, reflecting the film's ouroboros-like narrative"