Writer-director Natasha Kermani’s Abraham’s Boys, adapted from a short story by Joe Hill, asks audiences to suspend disbelief long enough to accept the revisionist idea at its heart. If one can do that, the film rewards with quiet dread, and some rich performances. The story is set in rural California, years after the events of Bram Stoker’s novel, in a bleak period where Van Helsing (Titus Welliver) lives in exile. The man is emotionally and spiritually spent. His wife, Mina (Jocelin Donahue), and their two sons, Max (Brady Hepner) and Rudy (Judah Mackey), live in a household ruled by silence, discipline, and simmering violence. It’s a portrait of domestic unease masquerading as order, with alarm seeping in through every closed curtain.

The first and most jarring premise is the most inexplicable choice, though it does come directly from the short story: Mina Harker is the wife of Van Helsing. For readers of Stoker’s original novel, this union is sacrilegious. Mina has long been associated with resilience, purity, and the sacred bond of marriage. In short, she is the new Victorian woman awakened. To sever that and pair her with the aged and haunted Van Helsing feels like narrative reinvention for its own sake. There is no backstory or emotional justification for this coupling, and Donahue’s take is composed and sympathetic, but she remains passive without the resilience usually seen in the character.

Abraham’s Boys does better when focusing on the sons. Hepner and Mackey portray the solidarity of siblings weathering a volatile parent. Hepner’s ability to highlight Max’s transformation from a state of observation to defiance is particularly stirring. This parallels Interview with the Vampire, where Claudia rebels against her maker, the father figure Louis. Both are a story of the child rejecting the legacy of the parent. It’s thoughtful and engaging, thematically speaking.

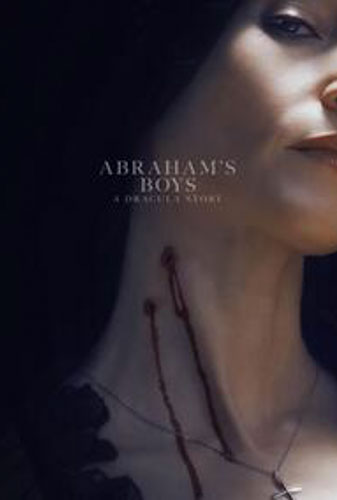

Promotional art for Abraham’s Boys, featuring Mina Harker and the telltale signs of a vampire’s bite.

“…Van Helsing lives in exile…wife, Mina, and their two sons…live in a household ruled by silence…”

Van Helsing, once the keeper of arcane knowledge, mystic turned monster-hunter, is rendered as an aged patriarch whose rigid, paranoid grip on his past becomes abuse. Welliver plays him not as a villain, but as a deeply broken man who has lost the line between vigilance and obsession. The tragedy is that Van Helsing believes he is protecting his family from evil when, in truth, he is perpetuating it.

If there’s a character who almost steals the show, it is Jonathan Howard’s Arthur Holmwood. In the original text, he is the noble Englishman, the man of title who loses Lucy and helps by eventually financially backing Dracula’s destruction. Arthur’s presence in Abraham’s Boys suggests that aristocratic virtue has been replaced by ineffectuality, implying that the future belongs to the flawed and orphaned, such as the Van Helsing family.

Kermani, known for her feminist and trauma-centred horror, does not offer jump scares. Instead, she delivers a creeping dread of old evil, a fear rooted in upbringing, repression, and the unreliability of memory. She impressively fills the frames with muted palettes and careful period detail. One wishes that the dialogue carried the same weight. Much of the story is dialogue-heavy, especially Van Helsing’s numerous speeches. The emotional weight often outpaces the writing, which too frequently tells us how characters feel rather than showing us. Still, the emotional center — the examination of inherited trauma and the myth of the protective father — is intense.

Abraham’s Boys asks uncomfortable questions: What if the people who save us also break us? What if the lessons we inherit are poisoned by obsession? Kermani shows that one can revise a classic text if there is reverence for what has happened in the past. This film emerges as a thoughtful, Gothic tale in the tradition of Anne Rice, rather than Bram Stoker, as it is less about monsters and more about their legacy.

"…delivers a creeping dread of old evil, a fear rooted in upbringing, repression, and the unreliability of memory."