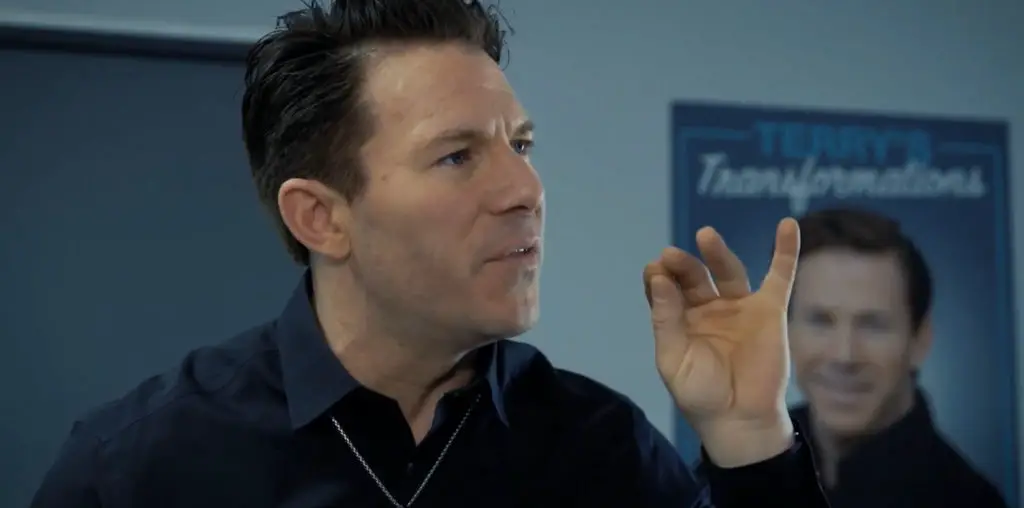

A Still Small Voice is a painful film about a nurse’s struggles to comfort her dying patients. Directed by Luke Lorentzen, it follows Margaret “Mati” Engel as she completes her residency in spiritual care at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital. Her program is supervised by Reverend David Fleenor, the other main subject of the documentary.

Mati’s job is an unenviable one: she comforts dying patients before they meet their Maker. Understandably, Mati’s outlook on life is tinged by pessimism and distress. She cannot cope with the harsh realities of suffering, which she encounters on a daily basis at the hospital.

A Still Small Voice is structured as an interplay between two psychological roles: the patient and the caretaker. Both of them are played to maximum effect by our protagonist, Mati, whose distress becomes our own. To her boss, she lays bare her unnerved mind, fraught with exhaustion and fatigue. But to her patients, our heroic nurse must muster up the courage to provide the spiritual and psychological healing needed to alleviate their pain.

Mati struggles immensely to make sense of this bleak world she sees. “I have no idea where my prayers are going,” the poor woman admits forthrightly. From this film’s perspective, healthcare is doing God’s work. As such, Mati is cast as a selfless saint, a martyr of altruism, who sacrifices her own well-being for the last-minute comforts of her perishing patients.

“…the story follows Margaret “Mati” Engel as she completes her residency in spiritual care at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital.”

Throughout the film, the claustrophobic camerawork is fairly observational about its hospital setting. Realistic colors and lighting are the norm. White walls, pale rooms, sterile environments, and blue masks form the dark film’s fatalistic end-of-life aesthetic. As hinted by the blue masks, A Still Small Voice expresses the anxiety, dread, and existential angst of the terrifying COVID pandemic. But it is equally true that this frightening film also represents the pandemic era’s boredom, malaise, and fatalism.

The movie’s title comes from an especially poignant scene where an elderly woman dying of lung cancer contemplates her miserable final days. “I go at my own pace in order to hear my own small voice,” she weakly croaks as Mati tries to console her. At certain points, the film’s thoughtful dialogue strikes many psychological cords with the careful observer.

A Still Small Voice engages honestly with tough philosophical problems, such as the existence of God, the problem of evil, the search for life’s meaning, and the soul’s odyssey beyond the grave. In one tear-jerking scene, Mati comforts a dead patient’s family member on the phone, who despondently asks her about the afterlife. “If anybody tells you they know an answer of where we go or what happens, I would say, ‘Don’t believe them,'” Mati tells her. The movie also reveals that Mati came from a family of Jews who the Nazis persecuted during the Holocaust. Her own history of tragedy and misfortune adds an intimately personal dimension to her questions about God, justice, and the hereafter.

But unfortunately, even these lucid moments of brilliant dialogue are unable to atone for a multitude of cinematic sins. The pacing is unbearably tedious, creating an unsettling mood that is as boring and sterile as it is pensive and philosophical. Even its best moments of dialogue cannot substitute the almost total lack of action or physical motion over the film’s inflated hour-and-a-half runtime. Although sincere and well-crafted, the repetitive lethargy of A Still Small Voice would perform much better in a short art film, not a full-length feature.

"…Mati struggles immensely to make sense of this bleak world she sees."