Kalbinur’s father feels uneasy about relocation. He does not want to leave his father alone. This scene is bathed in glorious natural light and elevated by its universality. Difficult conversations in which parents fret over aspirations for their children, changing schools, and the duties binding them to their parents and culture are hashed out in dinner tables and hearths across the world.

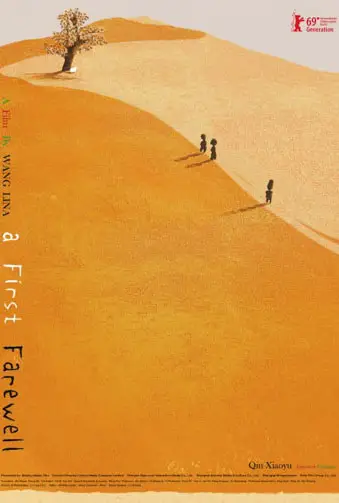

The performances Wang obtains from both the children and adults are extraordinary. The cast does a glorious job, to the point that the viewer is not sure if they are witnessing acting or documentary filmmaking. Every element clicks brilliantly because Wang combines character, setting, and cinematography to create a breathtaking whole. Wang films the children as if they are part of the landscape, blending into the majestic trees they climb and the dunes along which they merrily skip.

“…Wang combines character, setting, and cinematography to create a breathtaking whole.”

Two scenes stand out as some of the most sublime moments in my recent film memory. A heart-wrenching scene in which Isa, enveloped by shadows at night, desperately calls out for his lost mother, and the other is of Isa riding a donkey. Both are testaments to Wang’s talents, proving that her visual language ranks with that of established masters like Majid Majidi and Abbas Kiarostami.

If A First Farewell is Wang’s debut, it boggles the mind what her future films hold in store for us. She has captured a culture at the precise moment of transition. The landscape may be ancient, the village steeped in tradition, but there should be no mistake made, this is a culture in the midst of galloping change. When Isa reads an essay about a train in Uyghur, we are struck by the discord. He is reading in his language about the very thing that represents movement across vast distances, industrialization, change, and leaving tradition behind. We sense that for Isa leaving his village will be the first of many farewells in an everchanging Chinese economy.

"…a culture in the midst of galloping change."

It seems the rounding up and “re-education” of Uyghurs, removal from their land, and small little things like organ harvesting, never entered this reviewer’s mind. If a movie is made in China, it’s state-approved. The reviewer ignores that fact. Tibet couldn’t be reached for comment.