Other than a walk through South Williamsburg a couple of years ago, I have almost no experience or knowledge of the Hasidic community in America or any other Orthodox Jewish community. If you’re like me, 93Queen will first and foremost be an introduction to an insular culture that protects itself from outside eyes—not just Hasidic people, but Hasidic women. In an essay in Filmmaker Magazine, director Paula Eiselt (an Orthodox Jew herself) recounts how the strict “modesty codes” of Hasidic culture often discourage women from appearing in media at all. In light of that, we’re lucky to have this movie, which documents the lives and cultural concerns of highly religious women in the “Lean In” generation.

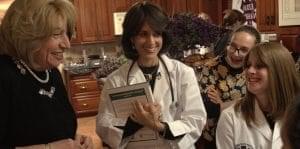

The central focus of 93Queen is Rachel “Ruchie” Freier, a Hasidic woman who, in contrast to the edicts of Hasidism, comes across as slightly immodest (in a good way). She is a mother of six who observes her religious duties to her family, but in the film, she is also a full-time lawyer who founded an all-female EMT corps called Ezras Nashim. The community backlash to Ezras Nashim is intense; with secular viewers in mind, Eislet guides us through the cultural barriers that make Ezras Nashim so controversial and so necessary.

“…a Hasidic woman who…is also a full-time lawyer who founded an all-female EMT corps called Ezras Nashim.”

In the Brooklyn neighborhood of Boro Park, home to a huge concentration of Orthodox Jews, there is an all-male volunteer EMT group named Hatzalah famous for its speedy response times. Because Hatzalah doesn’t allow women to join its ranks, Freier and many other Hasidic women think a female EMT group is necessary to serve the community’s women. In Hasidism, except in emergency cases, women are not allowed to touch or be seen naked/exposed by men other than their husbands. Even though Hatzalah is sensitive to this, Freier argues that the experience of being carried, handled, and treated by men during a medical emergency could be traumatizing for Orthodox Jewish women. A female option should exist for the comfort of those who need it.

Why aren’t women allowed in Hatzalah? There are no passages in the Torah that forbid women to drive ambulances. However, most of the Hasidic culture we witness in 93Queen sees women primarily as baby factories and homemakers, forbids women to shake the hands of men who aren’t their husbands, pressures women to marry and start producing children by their early twenties if not earlier, and sees modesty as the fundamental desirable trait in women. It’s not surprising that such doctrines foster sexism in many of their adherents. An anonymous member of Hatzalah tells the camera that there are simply certain roles that women are unfit for: we’ve never had a woman president, and the majority of CEOs are still men, so that proves women are less capable. The gender roles in this community are, by most American standards, extremely regressive.

“…a fascinating study of contradictions in values, made by and featuring women who want to transcend those contradictions.”

In this patriarchal environment, Freier is an anomaly, determined to trailblaze through professional milestones: the first Hasidic female lawyer, founder of the first Hasidic female EMT corps, and eventually the first Hasidic female judge. The film Is set up and ably edited as an “inspiring true story” of one woman leading others to break glass ceilings and conquer obstacles to their success. Freier is not just a go-getter, but a skilled politician who balances her responsibilities in ways that earn her community’s trust. In two telling interview segments, she rejects feminism (a bad word in Hasidism, apparently) as a secular ideology while claiming inspiration from the female activists who came before her. Her delicate balancing act isn’t without cost: some of 93Queen’s most heartbreaking scenes come when Freier doesn’t allow single women to join Ezras Nashim, which alienates some core members enough for them to quit.

93Queen ends on a happy note, a kind of victory for the “Lean In” brand of feminism. Women can have it all, even if they’re Hasidic! However, I left the movie with more questions than comfortable answers. Since Sheryl Sandberg wrote Lean In, we’ve heard arguments (including admissions from Sandberg herself) that “having it all” is impossible for a lot of women without the right resources. Yes, Freier has achieved great things, but her “always-on” personality is exceptional—what about the professional dreams of Hasidic women with more exhaustible wells of energy, or less support from their families?

There’s no question that Hasidism, by design, blocks most Hasidic women from professional accomplishments and public life. For that reason, 93Queen doesn’t soothe the anxieties about Hasidic sexism and gender roles that it raises for secular feminist viewers, even though it seems to want to. Ultimately, it’s a fascinating study of contradictions in values, made by and featuring women who want to transcend those contradictions.

93Queen (2018) Directed by Paula Eiselt. With Rachael “Ruchie” Freier, Tzvi Dovid Freier, Sarah Gluck, Yitty Mandel.

7 out of 10 sheitels