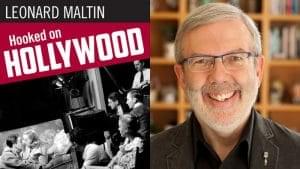

Leonard Maltin is a national treasure. So we jumped at the chance to present an exclusive excerpt from Maltin’s lated book, Hooked on Hollywood: Discoveries from a Lifetime of Film Fandom. Enjoy!

THE FORGOTTEN STUDIO: RKO REVISITED

Excerpted from Hooked on Hollywood: Discoveries from a Lifetime of Film Fandom by Leonard Maltin (GoodKnight Books) ©2018 by JessieFilm Inc.

RKO is, in many respects, the forgotten studio. It wasn’t created in the silent era, like Universal or Paramount. No one central figure was identified with it as Louis B. Mayer was with MGM or Harry Cohn with Columbia. What’s more, it ceased making movies in the 1950s, although its corporate name lives on.

As to its output, any buff can rattle off virtually all of the studio’s major movies during its heyday: King Kong, The Informer, Stage Door, Gunga Din, Bringing Up Baby, the Astaire-Rogers musicals, the Val Lewton horror cycle, It’s a Wonderful Life, Out of the Past, the John Ford films, and some other goodies with Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Carole Lombard, and Ginger Rogers, along with Citizen Kane. RKO’s top-drawer product fills a short list while a similar roster for MGM, Paramount, or Fox would take pages. This means that there are literally hundreds of RKO films unknown to film buffs and historians.

RKO’s creation at the dawn of the sound era from components of Joseph Kennedy’s FBO, David Sarnoff’s RCA Corporation, Radio-Keith-Orpheum, Radio Pictures, and Pathé Studios, is a saga unmatched by other Hollywood corporate histories. Its financial ups and downs over the years, and revolving-door studio heads (William LeBaron, David O. Selznick, Merian C. Cooper, Pandro S. Berman, Dore Schary, and the notorious Howard Hughes, among others) pique one’s curiosity as to how the company managed to survive at all. Thank goodness the entire story has been documented by the eminent historian Richard B. Jewell in his books RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan is Born and Slow Fade to Black: The Decline of RKO Radio Pictures, published by the University of California Press.

There is also the matter of the studio as a releasing outlet. No other major company had so many films pass through its hands without retaining ownership. For many years RKO released the works of Walt Disney and Samuel Goldwyn along with other independent producers, including Sol Lesser (the non-MGM Tarzan films), International Pictures (before that organization merged with Universal), and Boris Morros (The Flying Deuces with Laurel and Hardy). David O. Selznick acquired the rights to films like Topaze, Little Women, and Notorious, while Pioneer Pictures kept Becky Sharp and its other early color films. Series like Dr. Christian, Lum ‘n’ Abner, and Scattergood Baines did not stay with the company, and even their backlog of Pathé Newsreels left the company when Warner Bros. bought that library.

RKO lost still more properties by selling major films to other studios for remake purposes, or not renewing certain rights, resulting in tremendous legal snarls to clear the films for viewing in recent years. Among these titles are Cimarron, The Animal Kingdom, Winterset, Hit the Deck, Little Orphan Annie, Of Human Bondage, Girl Crazy, My Favorite Wife, She, Roberta, and Bird of Paradise, to name just a few. Fortunately, many of these have now come to light, but some remain in limbo.

It is no secret that the television package was once owned by the C&C Cola Corporation, because C&C refilmed the main and end titles of every RKO feature to herald “C&C MovieTime,” obliterating the RKO tower trademark and any action or opticals that might have been on-screen at the head or tail of each film. Even worse, C&C altered the 16mm negatives and managed to cut off the end-title music on many features, leaving audiences hanging in the middle of an unresolved musical phrase. Fortunately, most significant titles have been restored in the years since Turner Entertainment acquired the catalog.

When RKO burst onto the scene during the first days of talking pictures, the company was looking to knock the competition for a loop with large-scale films like Rio Rita, based on the hit Broadway show produced by Florenz Ziegfeld and partially filmed in Technicolor. An announcement ad in the 1930 Film Daily Yearbook for Radio Pictures showed the Radio Titan holding the company’s lightning-bolt logo. The copy proclaimed, “Mightier shows…Mightier plans…Mightier progress. The Radio Titan Opens the Curtains of the Clouds and a New and Greater Year Dawns for the Most Spectacular Show Machine of All Time! A New and Mightier Pageant of the Titans Is Forming…Titanic in Conception…Titanic in Development…Titanic in Reality! And Marching Irresistibly to Leadership of the Modern Show World!”

The Show World found a hollow ring to these statements as the studio, after initial blockbusters like Rio Rita and Cimarron, settled into the same mass-production groove as its competitors. The hiring of David O. Selznick gave a tremendous shot in the arm to the company’s fortunes, and he paved the way for some of the studio’s all-time best films. But after his departure RKO concentrated on a handful of major titles each year, filling in the release schedule with programmers and vehicles for its contract players.

This is the forgotten product of the forgotten studio, and it bears closer scrutiny.

Every studio produced its share of “filler” during these years, and every backlog has its share of overlooked gems. RKO’s list is especially intriguing since so many films fit into this category. The studio had its own formulas. One was to take talent from the short-subject unit and turn them loose in the arena of feature films. This accounted for some unusual and rewarding work by Mark Sandrich and George Stevens, who blossomed around the same time and became RKO’s leading contract directors in the mid-to-late 1930s.

Director John Cromwell told me that he enjoyed his period at RKO in the mid-1930s when he was able to make “little” pictures like Jalna and Village Tale, although he had difficulty getting major stars to work in such seemingly unremarkable properties. Consequently, RKO didn’t feel it could successfully promote these star-less films. They were treated as Bs although they really weren’t. Cromwell found them satisfying because they were “real and valid material, and not the usual concoction that you got from most studio writers.”

Another transplanted New York director, Elliott Nugent, rebelled at Paramount when they handed him B assignments but welcomed the opportunity to do a quiet character study at RKO like Two Alone. The studio’s perennial problem was in marketing these pictures.

Other directors have said they enjoyed working at the studio because there was none of the stagnation that existed at companies like MGM. The reason was simple: no management regime was in power long enough to settle in that way, and men like Selznick, Cooper, and Berman gave directors a chance to try new ideas. Consequently, more modest but offbeat pictures came out of RKO than from any other studio. Like Columbia, RKO borrowed stars and directors, or signed them to short-term contracts, and the results were often felicitous.

The look of RKO pictures was largely determined by the art direction of Van Nest Polglase and Carroll Clark. Polglase’s name has become synonymous with the lavish white-on-white moderne settings that we all remember from the Astaire-Rogers musicals. These sets and the photography of David Abel, Nick Musuraca, and Roy Hunt gave all the studio’s films a certain veneer that set them apart from those of other mini-majors like Columbia.

In the early 1930s Max Steiner wrote virtually all the title and background music for RKO releases. This was primarily during the Selznick regime, and while the scores of King Kong and The Informer have become classics, Steiner did equally impressive music for such films as She and Symphony of Six Million. For many pictures title music was all that was needed, and the studio often reused cues from earlier films. (Morning Glory’s main theme turns up under the credits for Two Alone, for instance) There was also “a song” at RKO. Whenever an incidental song was needed for someone to hum, to be played on a radio, or sung in a two-reeler, the answer was “Isn’t This a Night for Love?” written by Val Burton and Will Jason and introduced by Phil Harris in Melody Cruise. Harris sang it again in a two-reeler called Romancin’ Along, Ruth Etting crooned it in one of her starring short subjects, and it echoed through RKO soundtracks for the rest of the decade. No studio ever got more mileage out of a song, except perhaps Universal with “Swan Lake.”

Here, then, is a random sampling of modern-day viewpoints on a group of RKO films: some obscure, some ignored, and some merely worthy of another look.

Street Girl (July 30, 1929) directed by Wesley Ruggles, with Betty Compson, John Harron, Jack Oakie, Ned Sparks, Guy Buccola, Joseph Cawthorn, Ivan Lebedeff. Songs by Oscar Levant and Sidney Clare. Predictable but charming little film with likable performances all around. Harron, Oakie, Sparks, and Buccola are a musical group called The Four Seasons, joined by a petite violin-playing refugee from Aregon named Frederika (Compson). Harron falls in love with her, becomes madly jealous when the Prince of Aregon (Lebedeff) arrives in New York, comes to see Freddi at their nightclub, and kisses her. Discord is patched up when Lebedeff explains that he was only being kind, and he doesn’t love her. Says Harron, “Gee, you’re a prince, Prince.” The Four Seasons’ theme, “Huggable and Sweet,” is an infectious melody played frequently during the film, while “Broken Up Tune” is given a creditable production number. Remade in 1936 as That Girl from Paris, with Lily Pons in the lead and Jack Oakie in support.

Friends and Lovers (October 3, 1931) directed by Victor Schertzinger, with Adolphe Menjou, Laurence Olivier, Lili Damita, Erich von Stroheim. An unexceptional film made interesting by its cast. Menjou and Olivier are British officers stationed in India, both in love with Damita. When Menjou realizes the identity of Olivier’s fiancée, he tries to describe his former relationship with her by saying intently, “I knew her very well.” Von Stroheim is sheer delight in this film as Damita’s conniving husband, who blackmails her lovers in order to support his expensive hobby, collecting porcelain. He handles his slyly humorous dialogue beautifully, and a showdown scene with Menjou is delicious.

A Woman Rebels (November 6, 1936) directed by Mark Sandrich, with Katharine Hepburn, Herbert Marshall, Elizabeth Allan, Donald Crisp, Doris Dudley, Van Heflin, David Manners. One of Hepburn’s least-revived films turns out to be a winner, with a women’s liberation theme that makes it incredibly timely today. Hepburn rebels against her strict Victorian upbringing, and after personal tragedy becomes an outspoken feminist, publishing a magazine called “The New Woman.” The soap opera plotting pulls out all the stops, but everything is done with such style and conviction that it works. Herbert Marshall gives one of his best performances as a diplomat who loves Hepburn, and unlike most of the men in the film, respects her independence. When he tells her that she hardly fits into the category of a helpless female, she replies, “Don’t you think men invented the idea of the helpless woman for their own protection?” By no means a preachment, the film also avoids the pitfalls of painting its characters in blacks and whites only. A rare dramatic venture for director Mark Sandrich, A Woman Rebels is certainly due for wider exposure, as an example of first-rate storytelling, first-rate Hepburn, and further proof that not every Hollywood film of the 1930s had its head in the clouds.