As we prepare to savor every episode of the new Twin Peaks, we thought it might be helpful to take a look back at a David Lynch interview from our archives. Please enjoy with a hot coffee and a slice of pie. (From the archives, originally posted in 2000.)

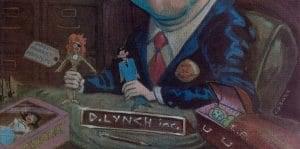

David Lynch has a painting hanging in his office. It’s very lovely, and very David Lynch. Just how David Lynch is breathtaking.

For you see, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the center of David Lynch’s very lovely canvas is dominated by a very old, very large slab of roast beef. Attached to one side of the meat is a mummified squirrel. And to the other side, a dead bird. The squirrel and the bird are covered, like the beef, with a thick, clear, gleaming layer of varnish. They’re all dead. Wrapped in plastic. David Lynch talks about the painting with the enthusiasm of a teenager, using words like “neat” and “cool.” (“I’m sending it to an art show in France,” he declares.)

Lynch has worked at a deliberately slow pace… producing seven films over 25 years, including Eraserhead, The Elephant Man (for which he was nominated for an Academy Award), Dune (1984), Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), the 1992 Twin Peaks movie, Fire Walk With Me, Lost Highway and The Straight Story.

Lynch’s films have often been accused of being weird. But they’re not. No more than real life, anyway. The truth is, life does not unfold like a three-act screenplay with snappy dialogue and a tidy ending. (Can you imagine if it did? Now that would be weird.) Lynch’s films are simply more attuned to life’s stranger moments.

Where do you get your ideas?

I really believe there’s, like, an ocean of ideas. And all of the ideas are sitting there. They bob up from time to time and come into your conscious mind and you know them. When a good idea bobs up, it really smacks you. It’s like a piece of electricity and you see the whole thing and you feel it and you know what to do. It all comes with the idea.

Since film is basically the art of compromise, how do you get away with what you do on the screen?

Well, you don’t. You don’t compromise. Except that a person has to work with what they have. If you call that a compromise, then you compromise. There are many, many, many things that you’re forced to dream up to make do with what you have, but it’s not a compromise. It’s just different ways to skin this cat. I really believe that even if you just have a little bit of money there’re ways to get into that film and make it work without a compromise. It may take a long, long, long time, like in Eraserhead. We didn’t have the money but we had the time.

Right. I should have rephrased it and said “For many in Hollywood, film is the art of compromise.”

Well, I don’t know, I think that a lot of people are able to get what they want and the one way to get what you want is to have had a hit film. Where there’s compromise, to me, is in a studio situation. And I don’t really know about it too much. But more and more there’s not just one person at the head of the studio that can make the decision. There are, like, committees of people, and if I ever had to go through a committee, I would be in big trouble, because they all want to understand the picture and I don’t want to explain in words and not only don’t want to, but I can’t sometimes, you know what I mean? I love the delicate abstractions that cinema can do and only poets can do with words. Maybe if I could write a poem to them, but it wouldn’t work anyway.

“There are, like, committees of people, and if I ever had to go through a committee, I would be in big trouble, because they all want to understand the picture…”

Do you want to have a hit film?

Well, I would like to have a hit film. A hit film means many, many people appreciate this particular film and that would be a unique and pleasurable experience for me.

It seems to me that you’ve had hit films on your terms.

Well, The Elephant Man was a pretty successful picture. But it was, you know, based on a true story. It was further away from what you say, a personal film, although I felt very personal about it and I got into that world, and I feel I didn’t compromise. Dune was the only film I’ve made that was a failure to me.

What about Dune? I always thought it succeeded on more levels than it failed.

Well, that’s nice of you to say. (Laughs.)

I mean visually speaking, it’s unbelievable. Maybe a two-hour, mainstream, big-budget sci-fi movie just wasn’t the right way to tell that story. Perhaps it would have been better as a 12-hour TV mini-series with a lower budget, and fewer whiz-bang, ray-gun special effects.

But the ironic thing is Dino (DeLaurentis)… I really can’t prove any of this… but Dino is sort of from the old school, where, in hyping a film, one of the things that they would say is “cast of thousands–millions of dollars spent.” This kind of thing. And that was just really the wrong thing to say about a film during (the early 1980s.) Plus, it may have been a “cast of thousands,” but it wasn’t the “millions” that he said. We were down in Mexico shooting. Our motion control system was antiquated even for those days. We were making do with almost nothing. I started selling out early on (in Dune), knowing Dino was a certain way. I knew I could only get away with certain things, and if I’d had a different kind of producer I would have just felt more freedom, and who knows what would’ve happened.

“Dune was the only film I’ve made that was a failure to me.”

So Dune you feel is the only time you’ve really ever compromised?

Yeah, I didn’t have final cut. If you don’t have final cut you’re in trouble.

You removed your name from a version of Dune shown on television and opted for the infamous Alan Smithee moniker…

I’ve never seen it and I took my name off because they added things in and did things that I wasn’t involved in, and so when it came to the crunch and I couldn’t do it… do the changes or agree with the changes… I just had to walk away.

Eraserhead is a cult classic. It seems to have the same kind of power it had when I first saw it. How do you feel about that film looking back now?

I used to say it was the perfect film, but now I don’t think it’s 100 percent perfect. Maybe 99 percent.

What’s the one percent?

I don’t know– nothing’s perfect.

Jack Nance has appeared in all of your films since playing the lead in Eraserhead. What is Jack really like?

He’s one of a kind, but everybody is one of a kind. But Jack, I would underline that. Jack is not motivated, that really is one of his only flaws. He has no motivation. I always said, if you want Jack for something, you have to go over to his house and get him spruced up and take him to where you’re working, because he sometimes doesn’t get there on his own. But when you get him, he delivers the goods. The guy is incredible, he is one of the best storytellers I’ve ever met. He’s got an unreal sense of humor, great timing. He’s interested in very strange things and holds in his head tremendous knowledge. He’s capable of great things.

I would like to meet him, it would be refreshing to meet someone in Hollywood who’s not motivated.

Yeah. (Laughs.)

“Because it was George Lucas’ film. He had already designed these little–bears; he had already done all this stuff. I didn’t understand why he wanted another director to come in.”

Star Wars fever is back and I know you had the opportunity to direct the third film Return of the Jedi. But you turned it down. Why?

Because it was George Lucas’ film. He had already designed these little–bears; he had already done all this stuff. I didn’t understand why he wanted another director to come in. It would really be George’s puppet on a string and I couldn’t see what my value would be. So it was very friendly. I was flattered that George even wanted me to. But I think he should direct those himself. They’re his things.

How do you handle criticism?

There’re two kinds. There’s destructive criticism and constructive criticism. I had a teacher at AFI (American Film Institute) that was named Frank Daniel, who passed away last year. The greatest teacher, not only for me, but all his students would say he’s the best. He practiced constructive criticism. I think criticizing something is– if it’s meant to make the following project better or if you have the time or the inclination to make it better, that’s constructive criticism. It gives you something to think about, you don’t have to do it, but it’s something to think about. Most critics… and that’s a general statement… are in the more destructive thing. They don’t care what it does to you, the director. I don’t know exactly what it is, but it seems sometimes it destroys something, and nothing good comes of it.

I think most of the press are concerned with, “Go see it”–“Thumbs up, thumbs down.” They get caught up in the horse race. On Mondays they report the film grosses–Who’s number one…

Exactly.

There’s not much appreciation for the experience. You really need to actually think about it, but that’s completely lost, at least in America.

I’m not a film historian or knowledgeable about film history or a film buff. But the critics should be. They should be able to appreciate many different types of cinema. Not throw one up against another and not get involved with the box office so much. See what really great cinema is, even though it’s sort of subjective. They, I think, could inspire an audience for many more different types of things and it’s just not happening.

“There’s no law against strangeness, it’s just the context.”

You have been accused by the media of being weird for weird’s sake…

Well, how do you spell, “Baloney?!” It’s just something that people say. It’s an easy thing to say. It doesn’t mean it’s true. To me, it’s completely wrong to do something strange for strange’s sake. It has to be an honest thing and it has to come from way inside. If you get an idea that you are in love with and you stay true to that, you can’t go wrong. But some of these ideas are strange, just like there are a lot things down the block that are happening that are strange. There’s no law against strangeness, it’s just the context. If you have contrast and interesting things based on true human behavior, then you’re okay.

I know you don’t like to do interviews.

No, because in an interview I like to do things that you’re really unable to talk about. You sort of end up talking about the surface of things or you say the same things many, many times.

I can just imagine how exhausting it is to do hundreds of interviews and being asked the 10 same questions over and over.

You sometimes stop and wonder why.

To plug the film, I guess. That’s the purpose. I hope that this interview isn’t too distracting.

No, it’s okay. (Laughs.)

In Lost Highway, there’s a brilliant scene where Robert Blake confronts Bill Pullman at a party and hands him a cellular phone then tells him to call him at his house… Blake is suddenly there. Where did that idea come from?

It just grows out of the idea that a person who understands fear could instill fear in another by suggesting super-normal things or magical things. It was sort of born out of something like that.

There’s also a particularly jarring scene where nothing particularly violent happens. Robert Loggia is talking to Balthazar Getty on the phone. He just keeps saying, “I just wanted to say you’re doing great. That’s great.” The scene is so frightening, yet it’s just a guy on the phone. How do you create that kind of intensity?

One of the things about film, it takes place in a way involving time. You kind of move down the road, and along the journey you introduce people and they perform actions, and if the actions are certain ways and you remember those things, then you can have a scene later on where your memory is covered with what they’re saying. You have a different experience, the same words said early in the film would hold not nearly the power. You have to have a certain knowledge and the character has to be defined in a certain way, so then he doesn’t have to say much.

I’m curious about you working with Bill Pullman. This is such a different role from him. He’s been in all this mainstream stuff. It just seems out of character for him.

Well, think of what you’re saying. Actors are hired because they seem to be a certain way. They get into this (typecasting) thing when they know in their heart that they could do 25 other things. As far as Bill Pullman goes, I’d see his eyes and something would come out of those eyes that made me know he was right for this role. I didn’t really think about what he had done before.

When you cast Wild at Heart, you never had Nicholas Cage or Laura Dern read for their roles…

I never read anybody. I’ve tested maybe one or two people because I was asked to, not necessarily forced to, when I didn’t have final cut and wasn’t able to make that decision myself. Just by talking to somebody I can tell right away if they can do the role. I worked with a casting director, Joanna Ray, and everybody she brings me I know can act. I don’t have to ask her, all I have to do is talk to them. Then we go from there.

What exactly do you look for?

It’s just a feel. They’re in the room and you’re talking to them and they may be quite a bit different than the character they’re going to play. Something is communicated and it’s just known right away. They hardly have to say anything. I just have to get a feel for them and then kind of verify it with a little conversation. Then you know if they’re right or wrong. Sometimes they’re wrong for what you brought them in for, but you get an idea if they would be perfect for something else. So you never know what’s going to happen.

“Well, she could be a brutalizer as well. You can’t say she’s just brutalized. She might be in the driver’s seat?”

What about Patricia Arquette? In Lost Highway, she’s brutalized in all sorts of strange ways.

Well, she could be a brutalizer as well. You can’t say she’s just brutalized. She might be in the driver’s seat? Again, it’s just a feel. I think I said somewhere that Patricia Arquette is the greatest young actress around in the world. She has got the stuff, there’s nothing that she couldn’t do. She’s super-intelligent, she’s beautiful, she understands human behavior and she’s courageous. When I was working on the editing, we kept seeing Patricia. Her performance was getting better and better. The more I watched, I started seeing the subtlest things and it was absolutely beautiful.

Sex and death are always somehow connected in your films and I wanted to ask if you know why that is?

Everything is connected in some way.

In particular, sex and death seem to come together…

Well, I don’t know.

Perhaps life’s two most intense experiences are those two. One you get to experience only once… maybe twice… if you’re lucky. Sex and death are very much a part of all of your work–

That could very well be. I never really thought of that.

Now is your chance…

I don’t know if that’s true. But give me an example.

Well, for example the scenes between Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette when they’re making love. Bill is disturbed, and Patricia ends up in the bedroom sliced entirely in half. That brings a violent and fairly gruesome conclusion to their relationship.

That relationship possibly could be in some sort of trouble. So every scene manifests to some degree, those problems.

I think there’s a lot of humor in your films. I’m just wondering if everyone gets it.

But there’s many different kinds of laughs. Some laughs come out of nervousness and some come out of generally funny things. So you never know. I think sometimes in a screening early on, when you’re still shaping the picture, you’ll get a laugh when you never dreamed you would get a laugh there. You have to analyze why this is happening.

When you’re making a film, or in the writing stage, do you think about how the audience is going to react to certain things?

I don’t think about the audience, really. I think about the ideas and I try to watch what’s happening to catch new ideas and listen to what’s happening or what someone’s saying. Keep acting and reacting all the way through the process, letting the ideas talk and staying true to the ideas that talk. I really feel that if you’re true to those things, like I said, an audience will appreciate that, the same way you do. But everybody is different. I always say that (Steven) Spielberg is a very lucky human being, because the things he likes, millions and millions of people like. The things I like, maybe thousands and thousands people like. But you have to be in love yourself and see these ideas unfolding. That’s how it goes for me.

“I don’t like television. I don’t like it because it forces a person to move too fast.”

How do you work on the set? If there’s something spontaneous that happens, do you just go with it? Maybe alter what’s on the printed page?

I’ve said this before, the script is super important, the story is super important, the structure of the story is super important. But even if the script is perfect, you still have to make the film and you don’t open the script up in the theater. In translating the script, if you just keep your eyes closed and just do the script, that’s fine. But things jump onto another level when I see actors come in costume. I hear them talking, acting and reacting and suddenly changing things or you get a whole new idea.

Visually speaking, Lost Highway seems to bring more shades of black to the screen than I’ve ever seen. The first half of the film is so dark, it just seems that there was quite a bit of time spent to create the look and the cinematography.

(Directory of photography) Peter Deming and I would talk a lot about mood. With (production/costume designer) Pat Morris, we would talk about mood and that gets into color and that gets into some shapes… the speed of the room, the speed of the people, and the mood of the whole thing. It all goes back to the original idea. So the production designer, the DP, hair and make-up… everybody has to tune in to that. Then they start operating in that area and it comes out fine. Always in the beginning it’s rough, then little by little we all get into that spot. Then it just follows. If you want something to happen visually and you haven’t done it before, then there’s some experimentation. Like early on we did tests on various things, so that when it came time do the real thing, it was like having money in the bank. We wouldn’t waste a lot of time experimenting with the whole crew. We tried to nail those areas down up front, so you can figure out the best way to do something.

Do you storyboard your films?

I don’t like to storyboard. For film, storyboards mean that’s the way it’s going to be. Many people lock into that. For car chases, and things like that, it’s helpful to storyboard. Most often, I’d rather go in with my own ideas and be able to change them after rehearsing or seeing certain things or having accidents happen, not harmful accidents. But strange accidents often lead to really interesting ideas.

Can you give me an example?

Well, it wasn’t exactly an accident, but there’s a shot that I wanted out of focus. But when Peter (Deming) de-focused it as much as he could, I said “Pete, that’s completely almost crisp, that’s not nearly far enough out of focus.” So he said the only thing we could do is take the lens out, so I said, “Take the lens out.” So he took the lens out and it was beautiful. So then we started taking the lens out all the time, it became a tool for saying a certain thing. We were doing that and we got used to calling it “wacking,” so we were wacking all the time. Then Gary Busey started working. We were in the front yard of a house and the camera was down on the ground… Gary and Natasha (Gregson Wagner) were up above. I guess Natasha had been working long enough to know about (“wacking”), but Gary stayed in character and everything, and then just had a huge fit. He thought they were goofing around or something. So we had to explain to him what was going on.

That’s funny. So, you literally just pop the lens off the front.

Unhook it, unscrew it and then just put it back in.

Switching gears on a goofball kind of comment, it seems that a lot of the lead actors in your films have the same haircut as you. You never noticed?

Really? That may be so.

It seems like a manageable haircut to have.

Yeah, it’s very manageable.

I know that you abandoned Ronny Rocket (a long-planned Lynch sci-fi movie project.) If you’re not going make it into a film, perhaps a graphic novel–?

Are you a psychic?!

Wha… you’re doing that?!

I’m doing that. It’s in the early, early stages.

To me, comic books are the closest thing to creating a film without actually making the film.

You’re a very sharp guy. That’s exactly what’s happening. It’s almost helpful to the film to realize that in another form and maybe see some things that may help you later.

I’m curious about Twin Peaks, which you lived with for years as a TV show, and later as a movie. Would you ever consider returning to television?

I don’t think so, but you should never say never. I don’t like television. I don’t like it because it forces a person to move too fast. Waterskiing works really good when you’re moving fast because you stay on the surface. But for a lot of things you want to go deep. I think television forces you into a shallow sort of thing.

There’s an interesting quote from Lost Highway, where Bill Pullman says, “I want to remember it the way I remember it in my mind, not necessarily the way it really happened.” That seems like you talking there.

That’s the downside to video. Memory, they say, is so subjective. But there’s a tremendous amount of possible beauty that can be added into a memory, like a nice varnish. If you were to see, after all these years, video of the actual event it could be devastating. I personally really appreciate Bill Pullman’s thoughts.

“Some laughs come out of nervousness and some come out of generally funny things.”