Alternative narratives to the animal-as-enemy entertainment trope do exist in film, including heartwarming stories in which humans approach animal-like creatures aiming to communicate with them. In Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 movie Arrival, seven-limbed aliens with octopus- and elephant-like features descend in spaceships hovering a few metres above Earth. Some humans want to launch an offensive military attack on the creatures, but that faction is subdued by academics and scientists. A linguist, Louise Banks (Amy Adams), learns to communicate with the aliens and receives an unexpected gift in return: fluency in their language, allowing her to see the future as if it’s already happened.

Popular stories can model more thoughtful relationships with animals: one where humans approach once-feared creatures with consideration and respect instead of treating them as de facto enemies. New narratives can inspire humans to overcome knee-jerk reactions by seeking to understand and accommodate animals rather than exploiting them.

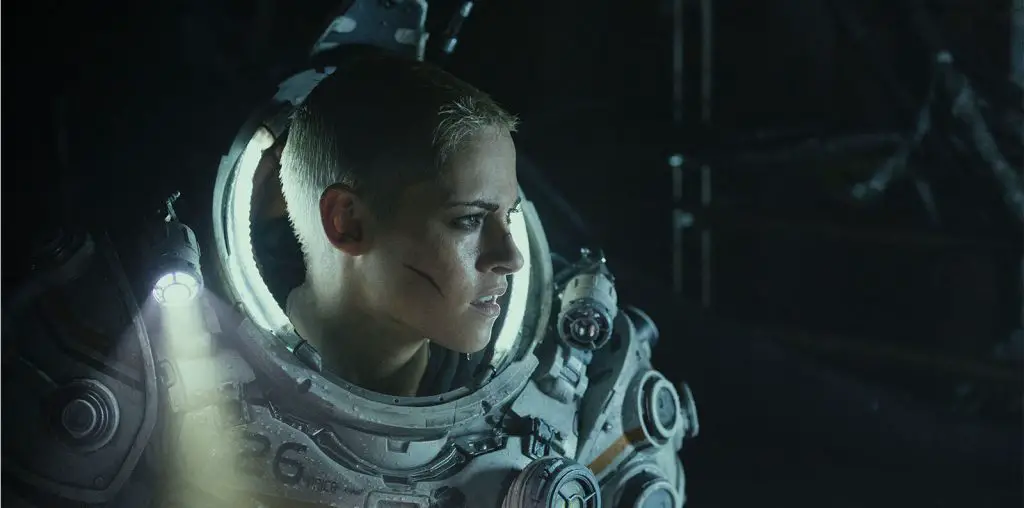

The film Underwater suggests that the familiar sea monster trope is overly simplistic by hinting at Cthulhu’s point of view. Consider that the monster may have had valid reasons to attack the human team. A research assistant, Emily (Jessica Henwick), from the rig team, suggests that Cthulhu is merely self-defending against colonial invaders. “We [humans] did this,” Emily says. “We drilled to the bottom of the ocean. We took too much. And now she’s taking back.” The gendered pronoun “she,” introduced here for the first time in the movie, suggests that Emily thinks of the creature as a being with her own motivations, rather than as a one-dimensional enemy.

“…learns to communicate with the aliens and receives an unexpected gift in return…”

Ultimately, the film does not entirely subvert the scary sea monster trope but does pay homage to the monster’s point of view. The animals demonized in films have their own understandable motivations—often, the impetus is to survive against human encroachment and antagonism. The colonialist viewpoint, which still prevails, that nature is an enemy to conquer, is immensely destructive to animals and ecosystems. The survival of many species, humans included, depends on a critical examination of this dated perspective.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with watching creature movies for fun, as long as we consider what ideologies our entertainment presents or reinforces. Movies too often uphold an ideology of human superiority by implicitly suggesting that humans have the right, or even obligation, to treat animals as enemies to be conquered. Fears of predatory animals may be partly instinctive, but these fears—which are generally not useful in the modern world—can be logically dispelled not just through education, but through entertainment, too. Films that exploit humans’ fears of other species inadvertently cause unjust, real-life consequences for animals. This narrative is an insufficient justification of our colonization of the natural world and the extensive death and devastation that results. Instead of accepting human-centred narratives without question, we can seek to overcome fear and better coexist with the animals with whom we share the Earth.

Alyson Fortowsky is a journalist, fiction writer, and activist based in Toronto, Canada. Illustration by Louisa Esposito.