“Zombies are fueled by a desire to consume vacantly, eating their way to the end of civilization, infecting us with their emptiness. Zombies are us, hollowed out. They emphasize what we can become when only a body is left.”

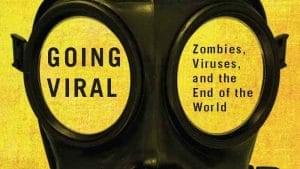

Our fascination with zombies has become a pop culture obsession. So it’s perfect timing for Dahlia Schweitzer’s new book, Going Viral – Zombies, Viruses, and the End of the World. Here’s an exclusive excerpt…

Going Viral: Zombies, Viruses, and the End of the World

By Dahlia Schweitzer

The preoccupation with zombies and the apocalypse fills both television and movie screens. To say the last two decades have mainstreamed zombies is an understatement. We have become increasingly fond of zombies and the post-apocalyptic narrative. Movies like the Dawn of the Dead remake (Snyder, 2004) and I Am Legend (Lawrence, 2007), the most recent filmic adaptation of Neville’s book, as well as television shows like The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010–present), Fear the Walking Dead (AMC, 2015–present) and The Last Man on Earth (Fox, 2015–present), play into our fascination with the idea of a post-apocalyptic world devoid of humans, governments, and technology, forcing survivors to adopt a ruthless neo-liberal ethos. These narratives look at what happens after an unstopped infection, after social order has broken down, after cities have been devastated and deserted. They play on the tension of what might be possible, preparing us for what may occur in a way that our families and our governments do not.

Zombie narratives, by their very conventions, speak to present-day America precisely because of how well they capture what feels like an eventual future (if not the actual present). Kyle William Bishop argues that “the aftereffects of war, terrorism, and natural disasters so closely resemble the scenarios depicted by zombie cinema . . . Scenes depicting deserted metropolitan streets, abandoned human corpses, and gangs of lawless vigilantes have become more common than ever, appearing on the nightly news as often as on the movie screen.” Zombie narratives play out the dystopia that already seems to be occurring. The empty streets, the packs of zombies, and the fetishization of guns, in particular, have now become tropes for a twenty-first century where war and the need for security feel just as ubiquitous as the threat of socioeconomic collapse and environmental crisis.

Another reason contemporary zombie narratives speak to present-day America has to do with their portrayals of networks with indeterminable centralized figures, with their emphasis on diminishing individuality and diminishing individual agency, and with their fusion of disease with fears of a terrorist attack. Even though the world was overrun with zombies in Day of the Dead, World War Z (Forster, 2013) is generally considered to be the first global zombie narrative because of its depiction of a worldwide fight to stop the outbreak.

“Zombies are us, hollowed out. They emphasize what we can become when only a body is left…”

However, the impact of globalization and a networked world could already be seen in the earlier Resident Evil franchise. The narrative arc of the franchise revolves around the global health industry, with a stronger emphasis on bioterror following 9/11. The central plot depicts a set of characters and their battle with zombies, caused as a result of exposure to the t-Virus, created by the Umbrella Corporation. The original Resident Evil film opens with a description of how the Umbrella Corporation has become the largest commercial entity in the United States: “Nine out of every ten homes contain its products. Its political and financial influence is felt everywhere. In public, it is the world’s leading supplier of computer technology, medical products, and health care. Unknown, even to its own employees, its massive profits are generated by military technology, genetic experimentation, and viral weaponry.” This prologue already establishes a global capitalistic world where one “umbrella-like” company impacts almost every aspect of contemporary life, hearkening to Gallo- way and Thacker’s description of a world where the “networks of FedEx or AT&T can be seen as more important than that of the United States.”18 While the first film and the sequel, Resident Evil: Apocalypse (Witt, 2004), both take place in Raccoon City, by the third film, Resident Evil: Extinction (Mulcahy, 2007), the destruction has gone global. In fact, one of the tag lines for the fifth film, Resident Evil: Retribution (2012, Anderson), is “When Evil Goes Global.” Not only does the series reflect fears of overly powerful corporations using overly powerful technology and bio-warfare to have their way, but it also demonstrates the way infected individuals are reduced to “animalistic, subhuman threats.”After all, the dehumanized are disposable, and the disposable are dehumanized.

Yet another reason for the zombie’s increased contemporary resonance also has much to do with its lack of centralized agency and control. In early Haitian incarnations of the zombie figure, as seen in White Zombie, a voodoo master controls and creates the early zombies. Similarly, Dracula is known for his ability to exert mind control over his victims. In contrast, the modern zombie terrifies because “no singular agent acts to possess the victim’s mind.” The zombie’s individuality and mind are both blank, replaced only with an insatiable appetite. Modern zombies drift aimlessly and mindlessly, driven only by their search of food, an appropriate shift considering that decentralized networks have become “the most common diagram of the modern era.”

The lack of centralized agency in an era of networked and global capitalism also results in a loss of individuality. Stephanie Boluk and Wylie Lenz, coeditors of Generation Zombie: Essays on the Living Dead in Mod- ern Culture, argue that, in an era of cloud computing, bots, and avatars, the possibilities for agency and individuality are “ever more restricted,” our subjectivity limited to “various network protocols of control.” Zombies embody fears of no longer being discrete entities (as people or countries), of losing freedom, identity, and agency. After all, the zombie is, as Marina Warner describes, “a body which has been hollowed out, emptied of selfhood.” Unlike Frankenstein or Dracula, zombies are stripped of their personal identity, losing their individuality as well as their connections to others. While vampires and werewolves can be seen as representing attractive states of being—primal, sexual, emotional, intense, and charismatic—becoming hyperbolic versions of themselves, zombies become empty versions, with no identity or consciousness. Zombies are fueled by a desire to consume vacantly, eating their way to the end of civilization, infecting us with their emptiness. Zombies are us, hollowed out. They emphasize what we can become when only a body is left.

—

Dahlia Schweitzer is a pop culture critic and writer. With a growing list of zombie and outbreak movies on the horizon, Schweitzer writes with wit and insight about our fascination with outbreak stories and zombies.