An apocalypse movie from Michael Haneke, the Austrian auteur best known for his unflinching observations on ultra-violence and self-destruction? It’s a foreboding, albeit unsurprising proposal. The director of such infamous misery-fests as “Funny Games” was hardly likely to venture into cuddly rom-com territory. In recent years, Haneke has fine-tuned his signature brand of bleak, extreme, cerebral arthouse with devastating results; his harrowing adaptation of Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher showcased Isabelle Huppert’s most potent performance to date, winning both director and actress major awards at Cannes.

Any sense of trepidation surrounding Haneke’s vision of a post-apocalyptic existence is heightened by his movie’s title sequence, which unfolds in deathly silence, white words on a black screen, and lasts for what seems like an eternity. It’s a sufficiently unsettling build-up for the film’s brutally shocking opening. In the still countryside, a vehicle approaches a log cabin. A family – mum, dad, son and daughter – climb out of the car and head inside, where they’re abruptly interrupted by a stranger with a rifle. He fires once, killing the father, then ousts the remaining family members from the house, sending them into the woods and setting them on a long and initially fruitless search for refuge.

Although we’re not spoon fed a backstory it soon becomes clear that some sort of disaster has occurred: rations seem hard to come by, there’s little electricity and the family’s neighbours are mostly unwilling to assist them. When this disaster may have happened is not made clear. Why it happened is also left unexplained. And while it looks like the present day, we’re never told the exact year in which the film is set. Haneke holds most of his cards close to his chest, releasing the tiniest pieces of information as and when he sees fit.

As the mother (Isabelle Huppert) leads her children across the film’s bleak, desolate landscapes, you begin to think that this must be exactly what life would be like for the survivors of an apocalypse. Each day consists of walking, wondering, waiting. In this respect, the early stages of “Time of the Wolf” play out like that extraordinary sequence in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later where Cillian Murphy staggers around London’s empty streets, desperately calling for attention. Haneke, like that film’s creators, is primarily concerned with the practicalities of life after an apocalypse. Rather than lingering on the cause, his movie studies the after-effects, focusing on the struggle to find sustenance, the fragility of newly forged relationships and the fear of the not knowing.

Boyle, however, was quick to unleash packs of rabid zombies to keep things ticking over, whereas Haneke offers no extravagant sci-fi trappings. His pared-down, unadorned approach is the perfect complement to the minimal dialogue, those barren landscapes and the equally exposed characters. In fact, the director’s shooting style often brings the film close to documentary. It moves at a deathly slow pace, grinding to a temporary halt when Huppert loses her son and searches for him in the dark. There’s a refreshing absence of “movie speak” and the characters react to situations in a way that we may well imagine behaving ourselves. While Haneke has often used music to staggering effect (think of the relentless drumming in “Code Unknown”) he offers almost no soundtrack here, allowing just two snippets of Beethoven, played on a portable stereo. The norm is silence, punctuated by frequent screams and some particularly resonant sound effects (scratchy footsteps, the spinning spokes of a bicycle).

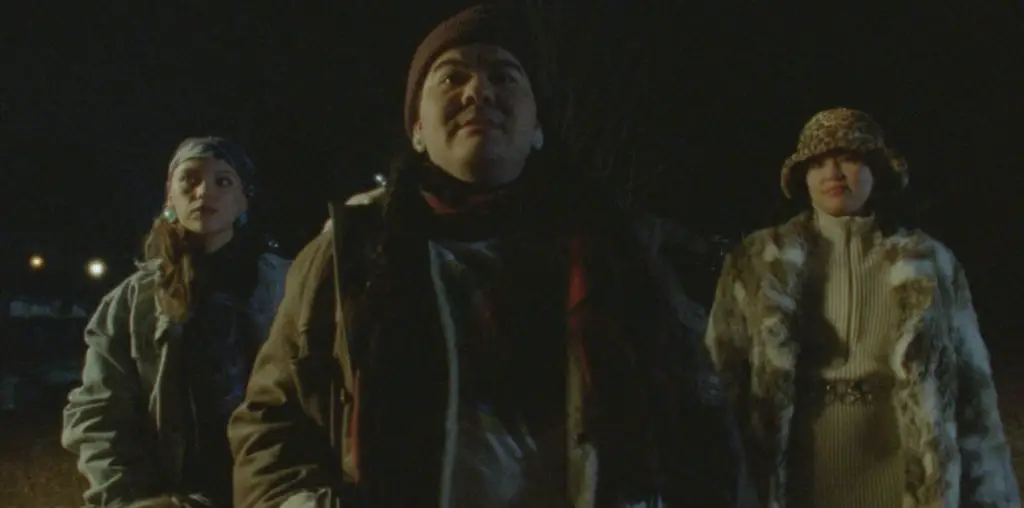

In 28 Days Later the horror of the zombies, scary as they were, was surpassed by that of Christopher Eccleston’s odious army boys, who take hold of the only female survivors and organize a session of ritual mating / rape. Haneke has similarly grim predictions for the future. When Huppert and her children reach a kind of shelter, populated by stragglers of mixed nationality, class and age (including a glum Beatrice Dalle and, bizarrely, “Intimacy” director Patrice Chereau), they learn that the self-appointed leader exacts payment in any available form from his wards. To survive, people are forced to trade whatever they can. One scene sees a pack of profiteers riding horseback through the land, selling water to the dehydrated. In desperation, one woman offers her body for a cup. Later, Huppert herself is raped at knifepoint in the middle of the night. When society breaks down, so do its rules…

In the somewhat muted lead role, Huppert really is a marvel. I last saw her playing a prim spinster in “8 Women”, François Ozon’s delectable murder mystery pastiche. The part seemed to spin on her disturbed turn as Haneke’s piano teacher, revealing a gift for comedy as well as tragic-horror. Here, re-teamed with Haneke, she burns with a quiet, white-hot intensity in what amounts to a razor’s edge performance. (Her daughter observes that she must weigh her words carefully or her mother will crack.)

Huppert and Haneke: they almost sound like business partners, purveyors of emotionally ravaging pictures. Certainly, they’re a formidable pairing, who have found in each other equivalent ambitions to test audiences, challenge themselves and push the boundaries of cinema. A film that’s easier to admire than enjoy, their “Time of the Wolf” is an unspeakably timely exercise in despair; an experience that leaves you feeling as exposed, as exhausted and as raw as its central characters. To sufficiently interpret Haneke’s rich, mysterious symbolism perhaps requires a second viewing but whether many would wish to take this journey again is another matter.