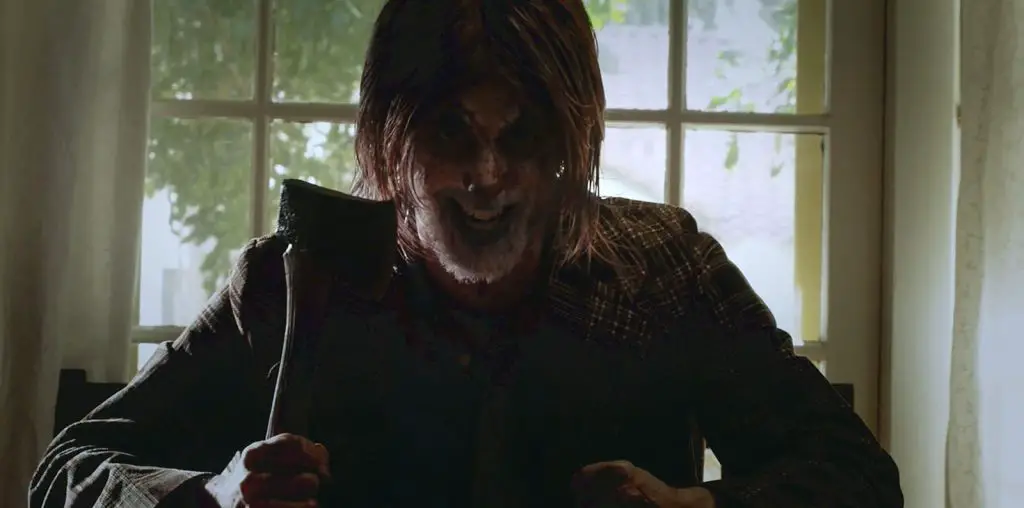

Stevie isn’t just another documentary. Unlike many releases in that genre, it isn’t just a fly-on-the-wall narrative in which the filmmakers are merely observers. This one is unique because director Steve James had a personal relationship with his subject. Because of that, I found myself interested in not only how Stevie’s troubles tore a tsunami through his family but also in how those problems affected James and challenged his ability to remain objective despite his feelings.

James knew Stevie in college, when he took the troubled young boy under his wing as part of a Big Brother program. Stevie’s mother didn’t want him and his step-grandparents had no legal right over him (he never knew who his real father was, and his stepfather died young), so he found himself cast adrift in the murky waters of Child Protective Services, where he was sexually abused while bouncing around foster homes. The trauma lit a fiery rage in him that even drug therapy couldn’t cure, and his teenage and young adult years became a litany of arrests and chronic unemployment.

In 1995, James reconnected with Stevie, deciding to make a small film that chronicled where his Little Brother wound up in life and the forces that pushed him there. After a two-year break to make another film (Prefontaine), he returned to resume filming and discovered that Stevie had been arrested and charged with sexual abuse. What he thought would be a minor project consumed two more years of his life as he tried to guide Stevie through the legal process while trying to reconcile his feelings for Stevie with the fact that he felt he was likely guilty.

Ultimately, James wanted Stevie to be placed in a counseling program instead of prison, an attitude that put him at odds with Stevie’s sister Brenda, who was abused by him as a child, and Stevie’s aunt Wendy, who was the mother of the victim and who initially viewed the director as the enemy. I found it fascinating to watch James navigate this tricky territory, trying to get people to speak honestly in front of the camera while convincing them that he will be objective. I can’t recall seeing another documentary where the director becomes such an integral part of the story.

Some may feel that this is a waste of film and that someone who committed the crime he did shouldn’t be worthy of a documentary, but they’re missing the point. Stevie is an indictment not only of the abysmal track record of child services in this country (look at the state of Florida, which actually loses children) but also of the generational cycle of abuse that afflicts so many people. Put those people in a low-income bracket that almost guarantees they will be neglected, and it’s heartbreaking to watch the resulting train wreck. When James introduces psych evaluations from Stevie’s childhood, complete with the statement that he was at high risk to sexually abuse a child later in life, the despair becomes palpable. How do you break that vicious cycle? It’s not James’ job to answer that question. His job is to pose it, and that’s the point of this movie.

Stevie is a depressing film, of course, but it’s also a very well crafted one. Several key events in the narrative, such as Brenda’s long-awaited pregnancy (she notes the irony that she couldn’t get pregnant even though she desperately wanted a child while her mother bore two children and couldn’t be bothered with either of them), dove-tail perfectly with the main storyline in a way that might seem contrived if this was a work of fiction. James even works within the basics of fiction (the three-act structure, rising and falling action, the climax and denouement, conflict and resolution, figurative guns on the mantelpiece, and so forth) to craft a narrative more compelling than many big-budget Hollywood movies.

In fact, during the production commentary track with James, cinematographer Dana Kupper, producer Adam Singer, and executive producer Gordon Quinn, the quartet notes several times how certain moments came across better than they would have if they had been scripted, thanks to the raw authenticity of the participants’ emotions. The crew’s gift for capturing cinema verite comes out even in the unused footage that’s included on this DVD. In one cut scene, for example, Stevie displays a map that shows his underground escape route from the dilapidated trailer he lives in, should there be a fire. When James points out that the booby traps in the tunnel are probably only there to stop the police should they be chasing Stevie, he stops and says “Well, yeah, you could use it for that too.” The comedic timing of the moment wouldn’t be better even if you used professional actors.

James notes at the end of the commentary that he was hoping to get some of the poems and art Stevie has written and drawn while in prison and put it on the DVD, but none of it is there. That’s a shame, but perhaps Stevie would like some privacy back after exposing so much of his life to James’ cameras, and that’s understandable. While the production commentary and unused footage are the extent of the extras, I can’t imagine what else you could ask for in this release. A documentary about the making of the documentary? At some point there has to be a limit to the navel-gazing.

Can’t get enough DVD? Talk DVDs in Film Threat’s BACK TALK section! Click here>>>