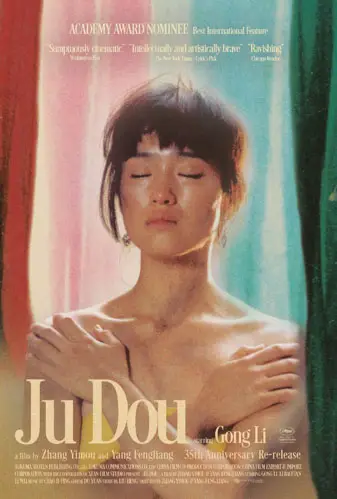

Few films demonstrate with such ferocious beauty how sex, power, and cruelty become indistinguishable under authoritarian systems as the Fengliang Yang and Yimou Zhang-directed classic Ju Dou, written by Heng Liu. Set in a rural Chinese family-owned dye mill during the 1920s, haunted by centuries of feudal oppression, this breakthrough melodrama remains as shocking today as it was incendiary upon release. With its lurid passions, saturated colour, and merciless fatalism, the film is not merely a tragic love story; it is an indictment.

“…Tianqing, a timid and economically powerless worker, listens helplessly as Ju Dou is abused nightly.”

The film is a brutal folk tale of Ju Dou (Gong Li), a young woman who is sold into marriage to Yang (Li Wei), the childless owner of a dye mill. He is an impotent, sadistic textile baron who believes torture is a substitute for intimacy. His adopted nephew, Tianqing (Baotian Li), a timid and economically powerless worker, listens helplessly as Ju Dou is abused nightly. Desire, inevitably, becomes rebellion. Their affair is initially tentative, as he calls her ‘Aunt’ and observes her secretly from a hole in the wall. One such moment, Ju Dou disrobes sadly to reveal bruises and whip marks on her body to the astonished Tianqing. Their liaison becomes defiant and produces a child that Yang believes is own.

The dye factory is not just a setting; it is the moral and symbolic core. Vast vats of colour dominate the frame — reds of passion and blood, blues of secrecy, yellows of harsh daylight. The result is an almost tactile intensity: with huge swaths of material everywhere, rolling down to dry in the sun. But the sex in Ju Dou is neither erotic nor romantic, even if it becomes an instrument of revenge. The act of making a male heir to the family business is warped by hierarchy, tradition, and surveillance. The lovers’ later brief moments of freedom, such as hiding in a cave, going for walks, are framed as transgressions against a system that cannot tolerate private truth. Ju Dou and Tianqing know whose child it is, yet let Yang raise him as his own out of fear of scandal and death from the townspeople. The film uses voyeurism, knowing exposure turns desire into a visual battleground. To look is to risk punishment; to be seen is to invite destruction.

"…as shocking today as it was incendiary upon release."