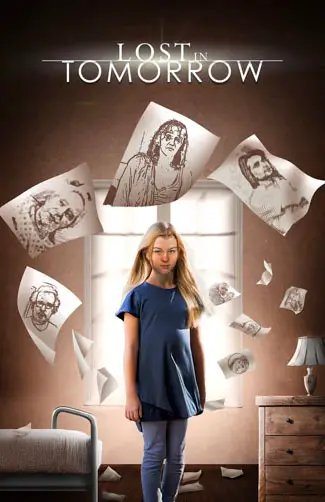

Writer-director Kellen Gibbs answers the question, “What if you were someone else for one day?” in his fantasy drama Lost In Tomorrow. Tween Harper (Charity Rose) is struggling at school. She’s been in a few fights and doesn’t seem to be fitting in socially despite being a bright, outgoing child. Harper’s retreat from the world is to draw portrait sketches in her room, which satisfies her desire to escape. One day, she lashes out after being bullied and is thrown out of school for attacking a boy who made fun of her. Harper’s mother (Julia Parker) insists that violence is never the right approach. Her father (Richard Neil) tries to console her. Harper feels as if everyone is ganging up on her, so she fatefully wishes she was someone else.

The next morning, Harper’s wish is granted when she wakes up in the body of an adult man. Now, Harper wakes up each morning in a different body, a new life, and possibly an alternate universe/timeline altogether. We join Harper on this magical mystery tour as she must cope with different lives every day. She experiences firsthand what it is to be an adult, a different gender, an elderly person, a parent, a married partner, a person of color, and many other situations from various walks of life. She literally walks in the shoes of other people. Harper now only wishes to make it back to her life with her parents. Will she make it back? Will these experiences inform her life going forward? Is this all a dream?

Lost in Tomorrow threads each jump with Harper’s fear of being inadequate and unloved. There is also the notion that this all may be an elaborate dream. Several discussions take place in which Harper mentions dreams, including wondering whether dying in a dream results in death in the real world. Her mother insists that dreams are not real. This means the film exists at the intersection between Quantum Leap and movies like Groundhog Day, Big, and It’s a Wonderful Life. There’s even a hint of Freaky Friday thrown in. Heck, we’ve seen some of these ideas explored in hits like Altered Carbon.

“…Harper wakes up each morning in a different body, a new life…”

The body swap is a now familiar trope in science fiction and fantasy. As such, a filmmaker has a responsibility to bring something new to that conversation when invoking it. Gibbs skips the low-hanging comedy/drama fruit of the shock a person would feel waking in a different body. He only slightly touches on Harper’s reaction to finding herself each day at various ages, genders, and entirely different universes/timelines where other people live in her parent’s house. This would’ve been a fascinating exploration of the physics/metaphysics of this universe, but ultimately, isn’t the point. What we get is purely Harper’s perception as she spins through different lives. This is more meditative than plot-driven. The director focuses on tone and awareness of context over plot rules or continuity. We never know what mechanism makes this journey for Harper, nor the rules of these hops.

The production quality throughout Lost in Tomorrow is good. The heavy lifting falls to the many actors portraying Harper as she rotates through physical forms and contexts. It sounds like an audition anecdote: “When you wake up, you find that you are a 13-year-old girl, but in your own body as it is right now. Action!” The performances are solid and authentic throughout. Some episodes resonate more, such as when Harper finds herself in the body of a dying 73-year-old man (Arthur Roberts).

What you take away from Lost in Tomorrow largely depends on what you bring to it. Gibbs delivers no preachy “do unto others” message. As Harper lives through different experiences, we gain some compassion for other perspectives and maybe even find some forgiveness for ourselves. Perhaps we get an inkling that isolation is an illusion, a kind of nightmare from which we can awake.

"…we gain some compassion for other perspectives..."

I didn’t understand the movie it jumped around too much nothing was explained confusing would not recommend for kids I’m 52 years old and have watched almost every time there is in this movie got on my nerves really bad don’t recommend at all

I’d like to hear from someone what happened after the credits – in Prime movie we saw, there was nothing after the credits.