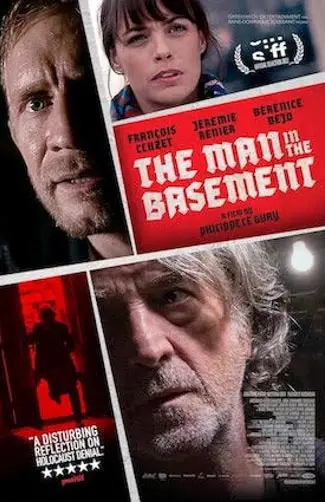

The Man in the Basement, directed by Philippe Le Guay, is a film about questions. In the areas where it succeeds, it does so largely by raising important questions. It is also marvelously acted and beautifully shot. But while many good questions are asked, often in striking cinematic frames, the film runs aground when navigating its characters, as well as the audience, toward insightful answers.

The story follows a young Jewish family living in Paris. Patriarch Simon (Jérémie Renier) is anxious to sell the family’s wine cellar located at the bottom of their apartment. In haste, he signs the deed away to the first polite stranger who expresses interest in it. But what Simon and his wife, Hélène (Bérénice Bejo), soon find out is that the man in the proverbial basement (François Cluzet) is a “revisionist,” or a Holocaust denier. With renewed haste, Simon endeavors to evict the man, but his every effort fails, causing a burgeoning spiral of tension throughout the family.

What makes The Man in the Basement important is the cultural context in which it exists. While questions about the reality of topics such as the Holocaust have obvious answers to the average person nowadays, it is the act of questioning — or rather, the institution of not questioning — that the film illuminates as sacrosanct in our society. Furthermore, it smartly utilizes the man in the basement not just as a villain but also as a projection of Simon and Hélène’s repressed hostility toward each other.

“…the man in the proverbial basement is a ‘revisionist,’ or a Holocaust denier.”

Adding to this complexity is the visual style. The Man in the Basement is shot with a wonderful French flair. Images are sumptuously composed, showing how even the most every day of settings possesses charm. It adds an intriguing metaphorical layer to the film’s veneer as the characters discuss the wars and internment camps of the past, not showing the scars of history but certainly feeling how deeply they cut.

Furthermore, the film is superbly acted by all of its cast members. Renier plays a calm but flawed father. Bejo is passionate but frustrated. As the titular man in the basement, Cluzet is simultaneously gentle and terrible. What becomes clear in Philippe Le Guay, Gilles Taurand, and Marc Weitzmann’s script is that no one’s motives are clean, even though they all try to appear that way—an austere reflection of how we, as people, act about our beliefs.

Yet while so much of the narrative groundwork is well-hewn, the handling of the character’s relationships is confusing, especially in the latter half. Everyone around him routinely chastises Simon for behaving in a civilized manner; worse, his family jumps to progressively histrionic reactions at every turn. These deliberate but unrealistic directorial choices make The Man in the Basement misleading. The film carries itself as though possessing great discernment but leads to a finale without insight. It is a critical sin to have no answers to a movie about questions. It is also a shame, as a greater delicacy in the approach would have surely elevated this to necessary viewing.

"…sumptuously composed..."