Japanese auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa is known for his masterful work in multiple genres, ranging from gripping horror thrillers like Cure (1997) to moving dramas like Tokyo Sonata (2008). His Wife of a Spy exists somewhere between the two, deceptively structured as a World War II film about international espionage, which slowly transforms into a nuanced exploration of the collectively crumbling human psyche. Unfortunately, it has been dismissed as “boring” and “disappointing” by some critics who keep comparing it to Hitchcock’s works. Such claims are amusing because Kurosawa has not attempted to make a thriller but a vivid deconstruction of one.

Set in Japan during the volatile year of 1940, the historical drama stars Issey Takahashi as an import-export merchant whose business is threatened by the rising international tensions. The rapidly changing socio-economic climate facilitates the overwhelming growth of fascism, most evident in the omnipresent influence of the Japanese government’s most formidable Repressive State Apparatus – the military police. Just like Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1969 masterpiece Army of Shadows, Kurosawa incorporates all the classics required for a gripping film about the resistance: a strong critique of nationalism, suspenseful games with the authorities, and carefully crafted misdirections.

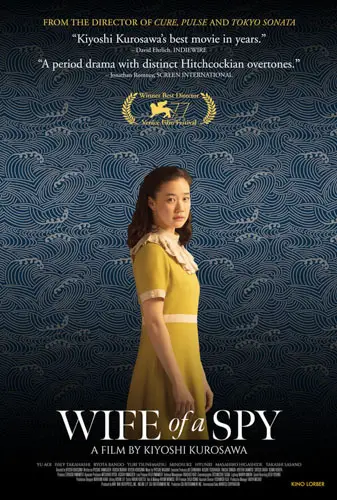

“…devoted wife who dreams of joining the resistance and fighting against injustice…”

There is, however, a key deviation from the usual tropes even though Kurosawa plays along with demands of the genre by occasionally indulging in deliberately artificial sound design, among other self-aware techniques. As the title, Wife of a Spy, suggests, the primary subject of the investigations isn’t the spy himself but his wife. Sadly, she is a figure who is almost always treated as an afterthought. Played by Yū Aoi, Satoko is an unreasonably devoted wife who dreams of joining the resistance and fighting against injustice but ends up as nothing more than a symbolic sacrificial lamb. This premise had a lot of potential to be a powerful feminist commentary on the exploitative relationship between women and war, but the film takes a different direction.

The film chooses to tackle a relatively lesser-known historical horror – the horrendous crimes committed by Japan’s infamous Unit 731. A covert outfit that conducted experiments on prisoners of war by injecting them with biochemical weapons, the unit’s inhuman actions are often glossed over due to the more well-documented atrocities in Germany. Kurosawa had the incredible opportunity of examining the visceral impact of Japan’s war crimes but adopted another approach. He focuses on the memory of war rather than the spectacle of human depravity on display in cult classics like Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985). Satoko comes across footage of Unit 731’s experiments, a narrative arc that Kurosawa uses to investigate the nature of these glimpses of humanity at its lowest.

Kurosawa is clearly obsessed with the artifice of the cinematic medium since the elegance of Tatsunosuke Sasaki’s cinematography makes every single frame look like a painting. Shots are composed in two dimensions are then punctured by the theatrical movement of characters in the third dimension. Wife of a Spy playfully experiments with the poetics of space and periodic melodramatic surges, but it all forms a part of the film’s more extensive meditation, insisting that the terrifying reality of yesteryears has been reduced to nothing but images enclosed within other images signifying nothing at all. That’s exactly why Kurosawa never exposes us to huge explosions or oceans of corpses, letting us experience the uncomfortable threat of small fires instead. Within the framework of modernity, historical empathy is a myth obscured by the retrospective distance of a borrowed knowledge.

"…obsessed with the artifice of the cinematic medium..."