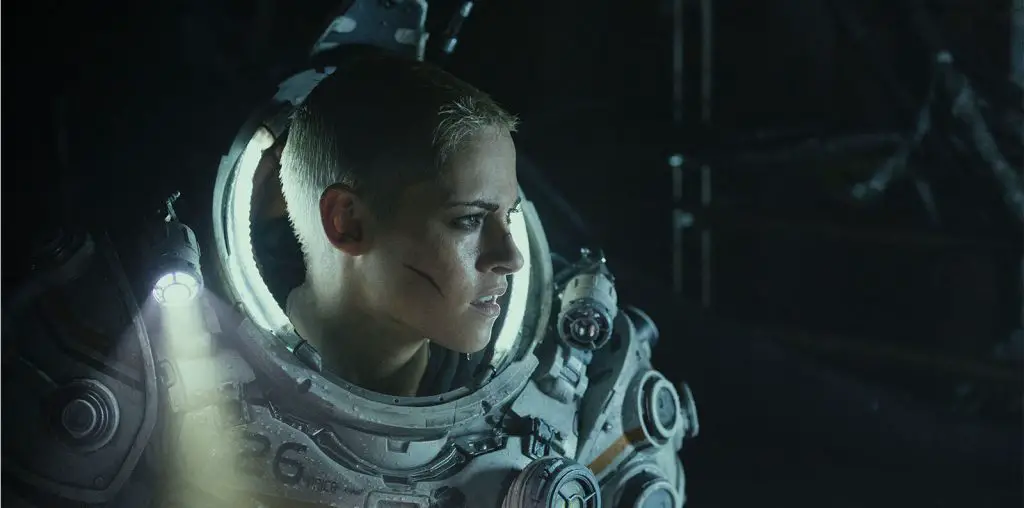

Seven miles deep in the Pacific, the last survivors of an underwater oil rig accident, in pressure suits, walk across the ocean floor—hunted and trying to get to safety. The humans see a flicker of movement in the pitch-black darkness and glimpse the predator—rubbery skin, flippered feet, and a spiny fin along its back. Its creator, a science fiction writer, describes the monster as having “an octopus-like head whose face [is] a mass of feelers, [with] a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind.” This scene is from the horror movie Underwater, 20th Century Fox’s recent addition to science fiction’s Cthulhu mythology.

Cthulhu, first introduced in H.P. Lovecraft’s short story The Call of Cthulhu, migrates to the depths of the Pacific Ocean from outer space—but despite the creature’s ancient alien origins, the film offers a twist on an oft-told story of the scary, mythical creatures who live deep in the ocean and hunts humans while moving with supernatural speed and strength in the unforgiving pressure and darkness of the Mariana Trench. The “terrifying” actions of these monsters provide insight into humans’ misguided fears about real animals.

“The sea monsters’ resemblance to real animals effectively inspires fear in humans.”

Most sea monster stories were created with no basis in reality, while others feature exaggerated images of existing species. Despite Cthulhu’s otherworldly origins, the monster’s tentacles, scales, claws, and wings derive from real animal features. This trope has been around since humans have been writing stories down. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus must sail between two sea monsters: Scylla, who yelps like a puppy, and has six “serpent necks” with “triple serried rows of fangs,” and Charybdis with a “yawning mouth.” Both kill humans without provocation. Scylla, the more animal-like of the two, eats six of Odysseus’ sailors. The Kraken of Scandinavian folklore is a giant squid that kills sailors as represented in a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson and in Jules Vernes’ novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. A giant squid is also mentioned in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, though it is, of course, overshadowed by Captain Ahab’s nemesis, the titular cunning white whale.

The sea monsters’ resemblance to real animals effectively inspires fear in humans. Yet none of the world’s underwater animal species, even predatory ones, are singularly fixed on human destruction. Blurring the line between real animals and fictional monsters—portraying fictional characters as exaggeratedly evil enemies—implies that certain species of “real” animals pose serious, existential threats to humans.

Monster stories become harmfully ideological when they demonize animals to justify human superiority; this demonization has real consequences for actual animals. The 1975 film, Jaws, presented an updated version of Moby-Dick’s monster whale: a vengeful Great White Shark. The movie spurred media hysteria about sharks, prompting thousands of American East Coast boaters, some with little fishing experience, to hunt sharks as trophies. Between 1986 and 2000, great white shark populations declined by 79 percent in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, while other shark species were similarly decimated. Worldwide, most sharks have died as commercial bycatch or for shark fin soup, not from sport fishing. The sharks’ damaged public image from film did not help conservation efforts.