Jim Exton’s bold attempt at Neo-Noir, shot on 35mm film with that fine favorite of low-budget filmmakers, the Arriflex 35 BL-2, falters more than compels. Exton well nigh hooks then loses us milliseconds before we are implicated in his almost-murderer’s self-torment and redemption.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly why the film doesn’t work, because everything about it appears so stunning and strong. We are strangely seduced by the protagonist’s smooth southern drawl and rippling muscles. Exquisite low-key, shadowplay against muted neon, weaves dreamscapes in our minds. Mark D’Errico’s lush score magically evokes suspense and Stephen Leet’s outstanding cinematography recalls Raoul Coutard’s roving pans and seamless, sweeping revolutions in such films as Jean-Luc Godard’s “Contempt” (1963). Yet, appearances can deceive, and none of these technical anchors can save “Four Years” from spiraling into cinematic purgatory, which is a real shame.

The story proceeds as Paul, played by James Buchanan, sits in his battered white pickup, photographing a man, who we later know as Ray, walking toward a slick, black car. Clumsily, and without feeling, Paul picks up and sets down the tire iron lying next to him on the seat. In what begins as classic-noir voice-over, he drawls, “Time…It can be your friend or your worst enemy.” Paul explains that it is four years since his girlfriend has left him, though he remembers this as if it is yesterday. Staring at a ring hanging from his neck, he tells us that two days before the breakup, he is about to present his girlfriend with an engagement ring. This will commemorate their first anniversary together. He is just about to propose marriage when “a man comes along and kills the one thing (he has) to live for.” This is enacted in a flashback where the girlfriend announces she is in love with Ray.

It is right there, in that opening voice-over, that the film sputters, losing all noir credibility as the protagonist’s vintage monotone disintegrates into varied annoying decibels. This may be due to audio issues, over-acting, or something else.

The scene beautifully transitions to Paul’s bedroom where he scrutinizes the ring against the light. Then we traverse, noir-fashion, to Paul throwing out boxes of relationship reminders, and retrieving certain pieces from the trash. In continuous voice-over, he tells us that after two years he cannot forget her, though he informs no one of his obsession.

Then, in an exquisitely lighted scene, we find Paul discretely seated in the back row of a movie theater. He tells us he “remembers (his girlfriend) with agonizing detail,” as Leet’s camera pans down to her – several rows below. We then transition back to the bedroom where the camera stations, voyeur-style, in back of Paul, where we see only his head and shoulders. He kneels bare-chested on the floor, masturbating to his former girlfriend’s photograph. This scene is disturbing in that it is so clumsily and sloppily enacted we do not immediately realize what is happening and only after revisiting the film three or four times, do we conceive that Paul is not having some sort of poorly emoted seizure. Again, we must (thankfully) imagine all this, as the camera shows an improper positioning of Paul’s shoulder, making his feat ambiguous, to say the least. The act completed, Paul lies down on the floor in an emotionless crying scene involving the same tremors as the preceding act. He then proceeds in a much better portrayal, to rip the photograph into numerous pieces. Then a fast cut shows him taping the remnants together.

Transitioning back to the theater, Paul describes Ray’s remarkable performance. “He work(s) the stage like a master…with the grace of a ballerina.” Paul characterizes himself as “a Neanderthal in Ray’s world.”

From there Exton cuts to the parking lot. It is nighttime. We watch from a distance as Paul flattens Ray’s tire then returns to the pickup awaiting his prey. The camera moves in, medium-close as Paul alerts Ray to his flat tire. Ray’s response along with subsequent dialogue is then lost as the audio drops. Ray picks up his cell phone. Paul drawls, “Oh hey, what’re you doing?” Ray responds that he is calling Triple A. Then, in the first and only portrayal of true emotion in the entire film, Paul transforms to the madman he is intended to be. “What’re you gonna do that for?” With impeccable timing, he checks himself and the monotonous drawl returns. While Ray attempts to change the tire, Paul sneaks up behind him with a tire iron. This favored weapon of choice has a long Film Noir history, appearing in such notables as Henry Levin’s “Night Editor” (1946), William Dieterle’s “The Accused” (1949) and Arthur Lubin’s, “Impact” (1949). More recent tire iron flicks include Alfred Hitchcock’s “Frenzy” (1972) and Stewart Hendler’s “Sorority Row” (2009).

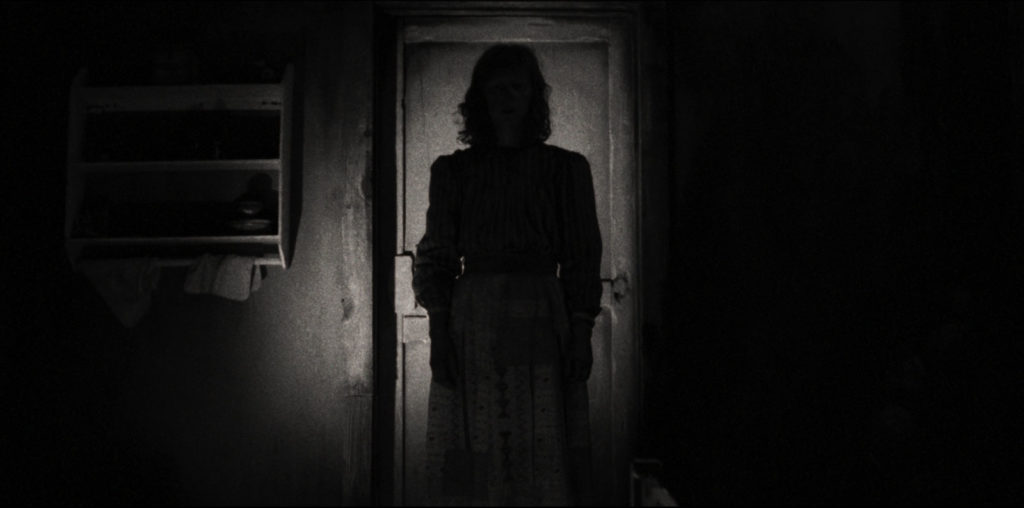

In another magnificently lighted scene, we can barely make out the whites of Paul’s eyes and the possibly crazed eruption lurking within. The complete lack of any facial close-ups in this film is a tremendous blunder in this key scene. At the precise moment Paul is about to strike, Ray confesses he hasn’t a clue how to change a tire. Paul stops, mid-bash with, “As far as I know, people haven’t popped off hubcaps in, like, thirty years.” Paul raises the tire iron again, this time not nearly as visually or psychologically effective, and eventually puts it down, agreeing to help Ray. The scene transitions to Paul’s office at the theater where it becomes apparent he is the Super. In a carelessly edited sequence where audio synch is not even attempted, Ray offers to pay Paul for his help. Paul declines both remuneration and handshake. In the final scene, Paul burns his X’s photograph. Unfortunately, a close-up on the blazing picture only pronounces a major continuity error. It is immediately apparent that Exton replaces the originally crumpled, torn and scotch-taped image with a smooth and clean new one. Whooops!!!

The closing voice-over feels a bit feeble as it moralistically poeticises Paul’s redemptive act. “Time…It can be your friend or your worst enemy. It can be on your side or work against you. In one second it was against Ray Hinsley and in the next, it was on his side….In that one second I realized the providence of my pain was not real….Ray had never entered my world. Our worlds were a galaxy apart.”

The good news about this sometimes brilliant, sometimes not enterprise is that time is clearly on Jim Exton’s side. Corrections may be made so that “Four Years” can yet be the powerful gem its filmmaker dreams it to be.